In 2018, the online Cold War Radio Museum presented for the first time to a broader online audience a secret 1943 memorandum sent to the Roosevelt White House by the U.S. State Department. The communication raised suspicions about John Houseman, considered to be the first director of the Voice of America (VOA) as being a communist sympathizer and too pro-Soviet to be trusted in a high-level sensitive government position in charge of U.S. radio broadcasts overseas.[ref]In his book, Voice of America: A History (New York: Columbia University Press: 2003), Alan L. Heil, Jr. does not mention the secret 1943 State Department memorandum about Houseman. Heil identified Houseman as the first VOA director: “Hollywood and Broadway producer, author and director John Houseman, another VOA pioneer and its first director…” (p. 36). Allan M. Winkler, who an assistant professor of history at Yale University published The Politics of Propaganda: The Office of War Information 1942-1945 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1978), accepted Houseman’s misleading account that he was denied a U.S. passport because Ruth Shipley, the head of the Passport Division in the State Department, “decided that his current alien status disqualified him for government travel at the time” (pp. 101-102). Houseman had obtained U.S. citizenship in early 1943 through the special intervention of Robert E. Sherwood, but the State Department still refused to allow him to travel abroad on U.S. government business because of his suspected Soviet and communist links.[/ref] The memorandum informed the White House that the State Department refused him permission to travel abroad as a U.S. government representative.

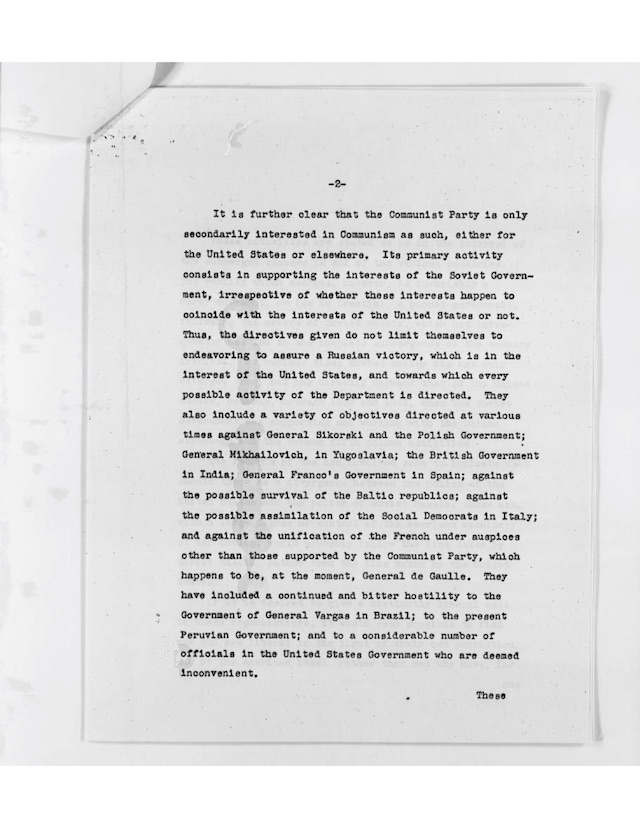

At the height of World War II, the U.S. diplomatic service and the U.S. military authorities had secretly declared the chief producer of VOA broadcasts to be untrustworthy because of his excessive pro-Soviet and communist sympathies. They came to this conclusion even though the Soviet Union was regarded by President Roosevelt as America’s indispensable military ally against Nazi Germany and hopefully later in the war also against Japan.

There were no direct accusations in the memo or details of any ongoing subversive activities. The most serious charge was that Houseman was hiring communists to fill Voice of America positions. This accusation against Houseman was true. Whether he did it on instructions from the Communist Party USA, or whether he had received and followed such instructions while working for the Voice of America, is not mentioned in the memorandum. How he did it was not specified. Soviet intelligence services would routinely use their influence to place agents or individuals highly sympathetic to the Soviet Union in U.S. government jobs. Even if the target of their activity was not a Communist Party member subject to party discipline, they knew how to manipulate those who participated in the Kremlin-controlled communist “front” organizations. A few weeks after Sumner Welles sent his memorandum to the White House, John Houseman resigned from his position as the head of the Radio Program Bureau in the Overseas Branch of the Office of War Information, the current day Voice of America.[ref]New York Times, “Radio Row: One Thing and Another,” September 12, 1943, Page 7.[/ref]

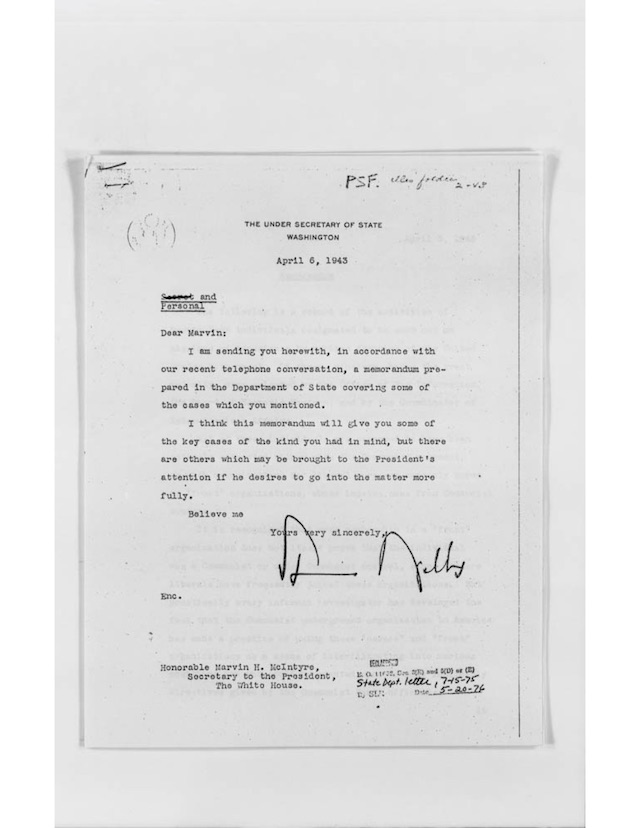

Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website, Box 77, State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944; version date 2013[/ref] and the National Archives State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, From Collection: FDR-FDRPSF Departmental Correspondence, Series: Departmental Correspondence, 1933 – 1945 Collection: President’s Secretary’s File (Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration), 1933 – 1945, National Archives Identifier: 16619284.

Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website, Box 77, State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944; version date 2013[/ref] and the National Archives State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, From Collection: FDR-FDRPSF Departmental Correspondence, Series: Departmental Correspondence, 1933 – 1945 Collection: President’s Secretary’s File (Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration), 1933 – 1945, National Archives Identifier: 16619284.

Only one piece of information in the attachment about John Houseman sent to the White House by Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles was false. Native Son, a 1940 novel by Richard Wright was not subversive or un-American. Wright, an African American writer, who joined the Communist Party, broke with it and condemned Communism in a 1949 collection of essays, The God That Failed. Another African American, Homer Smith, was one of the few journalists in Russia who did not join the large group of elite white Western correspondents in repeating Soviet propaganda lies about the Katyn massacre. Sumner Welles was one of the most liberal members of the Roosevelt administration and FDR’s close friend. Another piece of information about Houseman was only partly right. While he had a reputation of being a communist sympathizer, it is doubtful that he had formally joined the Communist Party.

But previously classified U.S. government documents show that following the start of Voice of America radio broadcasts in February 1942 in response to the dangers and the turmoil of the Second World War, the first group of VOA managers and journalists uncritically embraced and eagerly promoted various Soviet propaganda lies. Among them was perhaps the biggest and the longest-lasting Russian deception of the 20th century. For several decades, the Kremlin’s propagandists and their supporters lied about the 1940 killing by the Soviet NKVD secret police of about 22,000 Polish military officers and government officials in what became known as the Katyn massacre.

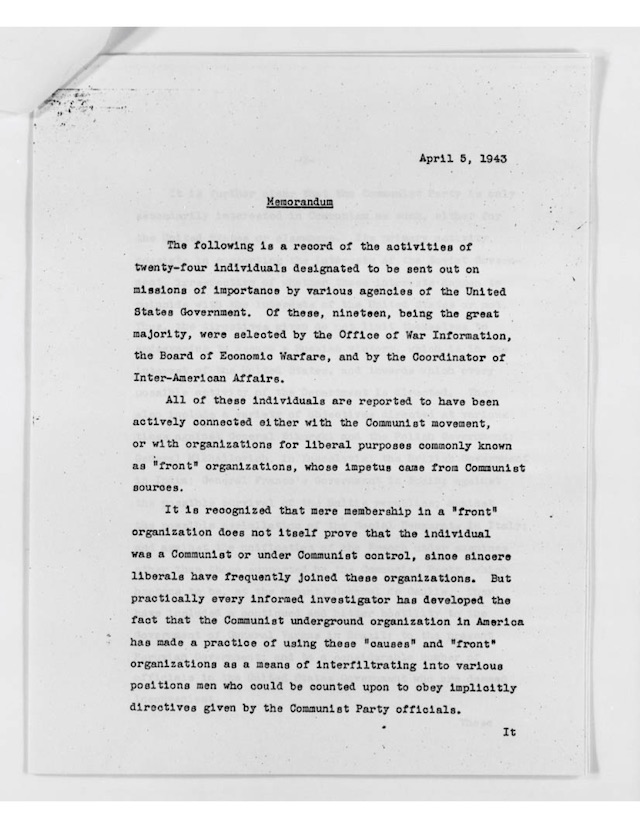

The memorandum about Soviet and communist influence within the wartime Voice of America included a cover memo written by Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles. He was a distinguished career diplomat and a key foreign policy advisor to President Roosevelt. Welles’ letter was sent to the White House on April 6, 1943. The attached memorandum with the addendum listing names of individuals who had been denied U.S. passports for government travel abroad was dated April 5, 1943. The documents were declassified in the mid-1970s and have been accessible online for some time from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website[ref]Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website, Box 77, State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944; version date 2013[/ref] and the National Archives[ref]State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, From Collection: FDR-FDRPSF Departmental Correspondence, Series: Departmental Correspondence, 1933 – 1945 Collection: President’s Secretary’s File (Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration), 1933 – 1945, National Archives Identifier: 16619284.[/ref]. It appears, however, that they have never been widely disclosed and analyzed before now. They were presented for the first time with a historical analysis on the Cold War Radio Museum website.

John Houseman (born Jacques Haussmann in Romania to a British mother and a French father; September 22, 1902 – October 31, 1988) was a theater producer, radio producer, and Hollywood actor now known mostly for his Oscar-winning role as Professor Charles W. Kingsfield in the 1973 film The Paper Chase and his commercials for the brokerage firm Smith Barney about making money the old-fashioned way. He emigrated to the United States in 1925 and worked as a grain broker before starting his theater, radio, and movie career and collaboration with theater and film director Orson Welles (no relation to Sumner Welles). They reportedly caused some amount of panic in much of the United States with their 1938 Mercury Theatre on the Air production of H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds which mixed genuinely sounding but fake evening radio news bulletins with dramatic descriptions of an alien invasion.

A 1982 Voice of America one-page biography mentioned Houseman’s collaboration with Orson Welles in producing the movie classic Citizen Kane. It also noted “the notorious Men from Mars [sic] radio broadcast [which] rocked [sic] the nation in November 1938” (it actually aired on Halloween, October 30, 1938 over the Columbia Broadcasting System radio network) but did not explain the broadcast’s significance as a pioneering experiment in fake news, in this case at least for purely entertainment purposes.

In late 1941 or very early 1942, John Houseman, whose legal name then was Jacques Haussmann, was officially hired by his friend, American playwright and Roosevelt’s speechwriter Robert E. Sherwood. Recruited, based on Sherwood’s and Nelson Poynter’s recommendations, he began to work for the Coordinator of Information, the U.S. government office in charge of spying, and propaganda. Through President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9182 issued June 13, 1942, the office of the Coordinator of Information was turned into the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), while the radio unit where Houseman worked became the Office of War Information (OWI). [ref]Franklin D. Roosevelt: “Executive Order 9182 Establishing the Office of War Information.,” June 13, 1942. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-9182-establishing-the-office-war-information. Last accessed May 6, 2018.[/ref]

Houseman’s hiring was not hidden from the State Department, which is where, according to his autobiography, he was interviewed by both Robert Sherwood and William J. (“Wild Bill”) Donovan, the wartime head of the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). It appears that the State Department and the Office of the Coordinator of Information, the future OSS and CIA, did not have initially any objections to Houseman being hired.

The later promoters of the John Houseman myth as a supporter of accurate news reporting and a symbol of VOA’s journalistic objectivity would be shocked to know that he was hired by the head of the U.S. intelligence agency in a meeting held in one of the State Department buildings, which may have also had the office of the Coordinator of Information. It is not clear whether any career U.S. diplomats participated in the meeting, but the chief of the U.S. spying agency did. If one is to believe how John Houseman described the meeting, the spy agency chief asked him to create the future Voice of America for propaganda warfare.

Such were the beginnings of the Voice of America. Its initial mission was to launch propaganda operations against Nazi Germany, Japan, and other fascist Axis regimes. What the U.S. intelligence service, the Pentagon, and the State Department may not have anticipated was the inclusion of Soviet propaganda in VOA broadcasts under Houseman and his immediate successors.

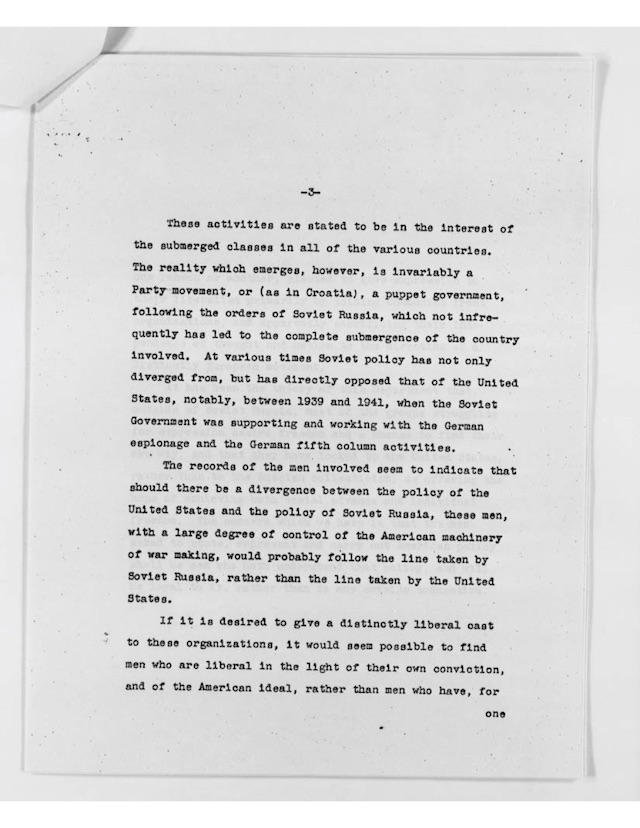

The memorandum Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles sent to the FDR White House in April 1943 noted the fascination of some American liberals with Soviet communism and urged finding other liberal individuals – not communist sympathizers – to be put in charge of U.S. government information programs.

If it is desired to give a distinctly liberal cast to these organisations, it would seem possible to find men who are liberal in the light of their own conviction, and of the American ideal, rather than men who have, for one reason or another, elected to give expression to their liberalism primarily by joining Communist front organizations, and apparently sacrificing their independence of thought and action to the direction of a distinctly European movement.