On January 12, 1944, Howard Fast, best-selling author, a Communist Party USA activist, and a future recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize, resigned under pressure from his position as the Voice of America (VOA) chief news writer and editor, in effect, the job of VOA’s first news director, and left federal government employment. His resignation was presented as entirely voluntary, and he received a glowing review of his performance from the Voice of America director Lou Cowan. In reality, he was pushed to resign by the Roosevelt administration officials in the State Department, who refused to issue him a U.S. passport for official government travel abroad.

The State Department, with the support of the U.S. military authorities, also refused to give a U.S. passport to VOA’s first director, John Houseman. In both cases, the Roosevelt administration, despite its strong support for the Soviet Union as America’s crucial military ally in the war against Nazi Germany, concluded that excessively pro-Soviet U.S. government employees like Houseman and Fast, were too risky to have influence over the hiring of staff and determining the content of Voice of America programs. Their departure, however, did not eliminate entirely Soviet propaganda influence in VOA broadcasts during World War II and for a few years after the war. Many other Soviet and communist sympathizers kept their jobs. But it was the start of a long process of making the Voice of America free from Soviet interference.

I established contact at the Soviet embassy with people who spoke English and were willing to feed me important bits and pieces from their side of the wire. I had long ago, somewhat facetiously, suggested ‘Yankee Doodle’ as our musical signal, and now that silly little jingle was a power cue, a note of hope everywhere on earth…1 Howard Fast, 1953 Stalin Peace Prize winner, best-selling author, journalist, former Communist Party member and reporter for its newspaper The Daily Worker, describing his role as the World War II chief writer of Voice of America (VOA) radio news translated into multiple languages and rebroadcast for four hours daily to Europe through medium wave transmitters leased from the BBC. Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), pp. 18-19. According to one description on the official Voice of America website, VOA adopted its “Yankee Doodle” station identification tune when John Chancellor was the VOA Director between 1965 and 1967 and had used earlier “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean,” but the information about Yankee Doodle being adopted by VOA in the 1960s may be wrong since it was in use before that time. However, Fast’s claim of having proposed Yankee Doodle as VOA’s station identification music theme during World War II could not be independently confirmed.

“The records of the men involved seem to indicate that should there be a divergence between the policy of the States and the policy of Soviet Russia, these men, with a large degree of control of the American machinery of war making, would probably follow the line taken by Russia, rather than the line taken by the United States.”2 Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles in previously classified April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President, with enclosures, justifying the denial to issue U.S. passports for official government travel abroad to VOA Director John Houseman and other Office of War Information (OWI) employees suspected of being Soviet and Communist sympathizers.

“There are still too many of the old OWI [Office of War Information] employees working for the Voice, both in this country and overseas. I mean those writers, translators and broadcasters who so wholeheartedly and enthusiastically tried for many years to create ‘love for Stalin,’ when this was the official policy of our ill-advised wartime Government and of our military government in Germany. There is no doubt that all those employees were at that time deeply convinced of the absolute correctness of that pro-Stalinist propaganda. How can we expect them to do the exact opposite now?”3 Journalist Julius Epstein quoted by Congressman George A. Dondero (R-MI) in Congressional Record, August 9, 1950. The quote was from the article which was published in the Evening Star Washington newspaper on August 7, 1950.

“They failed to acknowledge the human inclination to abuse power, ignored horrific consequences, and often rationalized Soviet barbarities as historically necessary. One of the benefits of examining the life of Howard Fast is that it enables us to make yet one more exploration into the hoary question of how this could have happened.”4 Gerald Sorin, Howard Fast: Life and Literature in the Left Lane (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012).

“Those broadcasts were lifelines to millions. Even more important, however, was the promise made right from the start: ‘The news may be good for us. The news may be bad,’ said announcer William Harlan Hale. ‘But we shall tell you the truth.’”5 Amanda Bennett, Voice of America Director, “Trump’s ‘worldwide network’ is a great idea. But it already exists.” The Washington Post, November 27, 2018.

“…starting in the first decade of the 2000s, the Chinese embassy in Washington, DC, and the leadership of VOA’s Mandarin service began an annual meeting to allow embassy officials to voice their opinions about VOA’s content.”6 A report of the Working Group on Chinese Influence Activities in the United States prepared by the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and the Center on US-China Relations at Asia Society in New York, October 24, 2018.

“This dynamic, on the whole, perpetuated to audiences the appearance of pro-regime propaganda, rather than objective reporting, on the part of both the VOA and Farda.”7 American Foreign Policy Council (AFPC), U.S. Persian Media Study, October 6, 2017.

“VOA has been too careful in avoiding anything that might look like a ‘anti-Russian’ bias….that could be regarded as a ‘pro-Russian’ (or, rather, pro-Putin) bias.8 Nikolai Rudenskiy, Voice of America Russian Website Evaluation, 2011.

Howard Fast – Voice of America’s Only Stalin Peace Prize Recipient

By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

Who was one of the first chief news writers for U.S. taxpayer-funded Voice of America (VOA), hidden for decades from history, who after leaving VOA and joining the Communist Party USA received the Stalin International Peace Prize worth over $235,000 in today’s dollars? Very few Americans know that the person who was in effect one of the first Voice of America newsroom directors was a Communist sympathizer and later a Communist Party member. While writing VOA English news broadcasts during most of 1943, he defended Stalin and refused to believe that the Soviet leader was a mass murderer. When he was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize in December 1953 several months after the death of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, he was one of the best-known Communists in America. He was later in a group of American Communists who cried when they read Nikita Khrushchev’s 1956 speech describing Stalin’s crimes, but he would neither repudiate nor return his Stalin Peace Prize. He never expressed any regrets about anything he wrote for VOA in 1943 and until his death defended his earlier support of Communism, Stalin, and Soviet Russia as historically justified and necessary.9

His granddaughter, Molly Jong-Fast (daughter of feminist writer Erica Jong of the Fear of Flying fame), recalled that the great Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, a fellow Communist, wrote a poem about her famous grandfather, with the line, You who are jailed. I embrace you, my comrade…10 In the period of McCarthyite hysteria and paranoia, he was briefly jailed, but not for anything related to his much earlier work at the Voice of America. He had refused to disclose the names of members in a pro-Soviet front organization.

Most Americans who are concerned about Russia and the influence of its propaganda on U.S. politics have never heard of him. Despite his once considerable fame and his key role as a pioneer Voice of America news writer, today’s VOA is silent about him. He was a best-selling American author, a contributor to a number of popular Hollywood movies, including Spartacus, which was based on his novel, and a reporter for The Daily Worker, the main newspaper of the Communist Party USA.

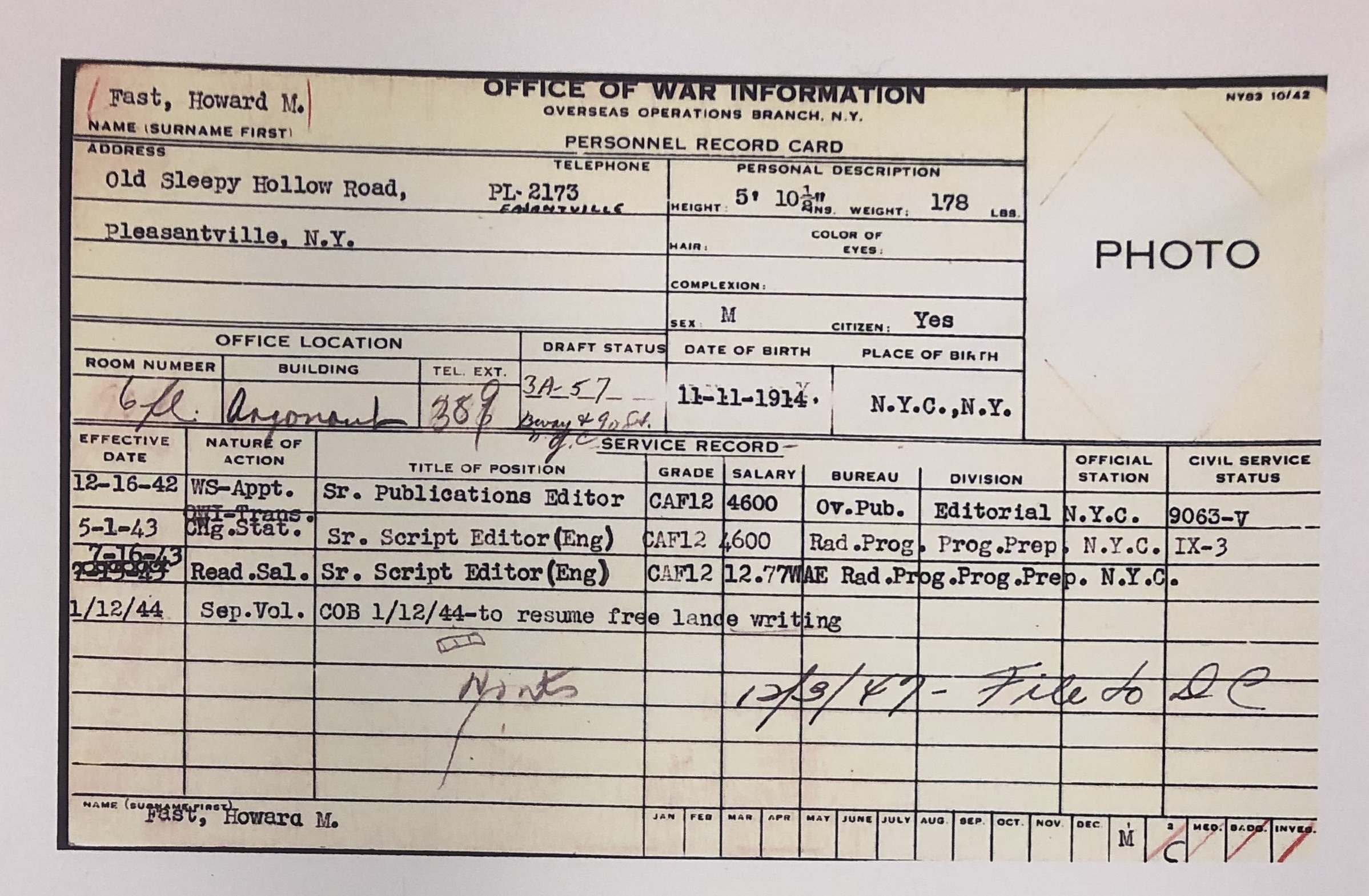

The approaching 15th anniversary (March 12) of the death of a prolific writer (near the end of his life, he had claimed to have written 75 books.) and VOA’s most famous Communist is likely to be completely ignored despite his great impact on the journalism of its early news programs. As a successful author of the best-selling historical novel Citizen Tom Paine, which received a front-page place in The New York Times Book Review, in 1943 he was put in charge of writing a 15-minute daily newscast for the premier four-hour Voice of America radio broadcast to Europe, referred to as “American BBC” because it was rebroadcast by a medium wave on transmitters leased from the BBC and was translated into multiple languages except Russian. Howard Fast was employed by the Office of War Information since December 1942. Documents in his U.S. government OWI personnel file show that he was officially transferred from the Publications unit to the Radio unit on May 1, 1943, but another document also indicates that he was already on loan to the Radio unit in March 1943. The exact date when he started working on writing VOA English news could not be determined from his OWI personnel records. He seems to indicate in his book Being Red that the transfer happened not too long after he was hired by OWI in December 1942.

The omission of Russian-language programming from early VOA radio broadcasts was not due to any lack of love for the Soviet Union and admiration for Stalin among its staff. Despite having dozens of other foreign language services, the Voice of America did not broadcast in Russian until 1947 because pro-Soviet U.S. government officials were afraid that Russian broadcasts might offend the Soviet leader. Not broadcasting in Russian or Ukrainian was a safer option, even though with pro-Soviet Communist sympathizers in charge of writing VOA news, producing radio programs, and censoring information unfavorable to Russia, chances of offending Stalin were minimal. The first permanent VOA English news writer-director (others, according to Fast, were fired after only a few weeks in this position) would not have received the Stalin Prize if he had done anything to harm the Soviet leader’s reputation. He earned his Soviet award the old-fashioned way by his hard work in promoting what one refugee journalist Julius Epstein who had escaped from Nazi Germany and worked for the Office of War Information called “Love for Stalin.”11 One of the very few anti-Communists at the Voice of America during the war, as a young student in Austria, Epstein was briefly a member of the Communist Party but quickly became an opponent of Communism and wrote about it both in Europe and later in the United States before joining the U.S. propaganda agency. After the war, he tried to expose to Americans the legacy of Soviet influence over VOA broadcasts and was criticized by VOA and State Department officials as an immigrant troublemaker.

“I do not know of any other case which shows so clearly that the policies of the Voice of America have sometimes exactly the same effect as if they had been designed and carried out by a well-paid Soviet agent than the way the Voice treated Stalin’s cold-blooded murder of 15,000 [the figure known at that time] Polish officers who were massacred on Soviet soil in the spring of 1940. As I already mentioned, the OWI accepted Stalin’s big lies on Katyn (that the Germans had murdered the Polish officers) at face value and disseminated those lies all over the world. When, after the war, a large amount of irrefutable evidence became available, evidence to the effect, that not the Germans but Stalin’s own NKVD had massacred the Poles, in order to get rid of the most valuable future anti-Stalinists in Poland, the Voice of America kept silent.”12

While still working at the Office of War Information, Julius Epstein had tried to warn his superiors about Communists being in charge of preparing Voice of America broadcasts. His warnings were, however, ignored and he himself was eventually pushed out of his job. For several years, VOA remained firmly in the hands of pro-Soviet propagandists.

Unlike Julius Epstein, the head of VOA news and the future Stalin Peace Prize laureate was a big shot at the wartime U.S. propaganda agency. He was selected for the job because of his earlier literary achievements and excellent writing skills, combined with the right ideological outlook. He reported directly to the top management and bragged that “…the entire organization was in a sense my staff.” While he prepared VOA newscasts, he could have anything he wanted just by asking, he wrote in his memoirs and claimed credit for having selected as a joke Yankee Doodle for VOA’s signature tune. To his surprise and amusement, his idea, he claimed, was accepted by the management. His claims, however, should be taken with a grain of salt. His granddaughter, Molly Jong-Fast, wrote that she was amused when in later years “a foreign news crew would come over and interview Grandpa for some documentary, because we just knew that 65 percent of everything he said was either a major exaggeration or a total fabrication.”13 Whether he was the person to suggest Yankee Doodle as VOA’s station identification tune could not be confirmed. According to one description on the official Voice of America website, VOA adopted its “Yankee Doodle” station identification tune when John Chancellor was the VOA Director between 1965 and 1967 had used earlier “Columbia, Gem of the Ocean”).

The chief VOA news writer during the war saw his mission as defeating Fascism and protecting the Soviet Union, but he also described it later as a time of great adventure. Being already married, he admitted to having a brief romance at VOA with his “tall, dark, beautiful, and rich” secretary, whom, after the romance was over, he dismissively described as “my Bennington graduate, who couldn’t type.” In a rare display of frankness, he admitted to being arrogant while working at VOA, but excused it as unavoidable because of his “age and background.” 14

He could count on the forbearance of the management by being a protégé of another famous early VOA figure, first director, and future Oscar-winning actor John Houseman, who, according to a once-secret State Department memo, hired his Communist friends to prepare the broadcasts. Despite being a promoter of Soviet propaganda and co-producer of the pioneer fake news radio drama The War of the Worlds, Houseman is still hailed today by VOA as a defender of truthful journalism, his own pro-communist background, and love affair with Stalin entirely ignored, but the name of his key assistant has been erased permanently from VOA’s official history and is never mentioned even in whispers.15 Also hidden in obscurity are now two other early VOA Communists: Polish Desk journalist Stefan Arski, aka Artur Salman, and Czechoslovak Desk Director Adolf Hoffmeister. Arski was later an anti-U.S. propagandist and denier of Stalin’s crimes for the Communist regime in Warsaw and Hoffmeister was a diplomat for the Czechoslovak regime.16 The Voice of America has also been silent in recent years about its anti-Communist broadcasters—those journalists, such as the legendary anti-Nazi Polish fighter Zofia Korbońska who in the later years of the Cold War helped to reverse the legacy of pro-Stalin VOA propagandists.17

For those who may be wondering, I hasten to add that the journalist and Communist Party member for 12 years who in 1943 was in charge of writing the first Voice of America news broadcasts to Europe was not Angela Davis who had been an icon of anti-U.S. Soviet propaganda during the Cold War when she was in jail accused and later acquitted of being an accessory to murder. She was featured in two recent VOA programs without being identified as a Communist. VOA editors, who either do not know the history of Communism or choose to ignore it, presented her as a praiseworthy American champion of human rights, but since she was born in 1944, she would have been too young to have worked for VOA in its early years. Angela Davis was a member of the Communist Party USA and its candidate for Vice President in U.S. elections in 1980 and 1984. As a proud Marxist even after Stalin’s crimes had become widely known in the West, she had—according to various sources, including Russian Nobel Prize-winning author of The Gulag Archipelago Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, who was censored for a few years by VOA in the 1970s—refused pleas for help for imprisoned Czechoslovak human rights activists and Soviet-Jewish Refuseniks. She was a recipient of the Lenin Peace Prize in 1979, not the Stalin Peace Prize, which was the prize that the former first chief writer of VOA news had received in 1953.18

The pioneer of VOA radio newscasts and the author of books that sold hundreds of thousands of copies in the Soviet Union was also not the American broadcaster Edward R. Murrow, who is sometimes unjustly credited with helping to create VOA. Murrow would have been of the right age and could have worked at VOA in its early years, but he was not a Communist and was never employed by VOA as a news writer or in any other capacity.

Some Americans might have concluded from reading a recent Washington Post op-ed by the current VOA Director Amanda Bennett that Murrow was somehow strongly connected with VOA and responsible for truthful news reporting from the moment the first VOA broadcast went on the air in 1942. Bennett wrote:

“‘Truth is the best propaganda, and lies are the worst,’ said Edward R. Murrow, who helped create VOA.”19

Murrow, in fact, had nothing to do with the creation of VOA or its news during World War II. First VOA programs were created by extreme left-wing radicals: playwright and President Roosevelt’s speechwriter Robert E. Sherwood, pro-Soviet journalist Joseph Barnes, Communist sympathizer John Houseman, and the future recipient of what could now be called “Stalin’s Fools Prize.”

Edward R. Murrow had nothing to do with them. Many years later, he was the United States Information Agency (USIA) director for the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. VOA was then part of USIA, but had its own presidentially appointed and Senate-confirmed VOA directors. The Soviets would have never considered Murrow for either the Lenin or the Stalin Peace Prize, or would they want to publish his books in the Soviet Union.

Edward R. Murrow knew the history and was an honest news reporter who would have been appalled by VOA’s WWII pro-Soviet propaganda. He himself had tried to counter Soviet disinformation in his wartime radio reports from London, despite the fact that the Soviet Union was at that time America’s important military ally against Hitler, having been earlier Hitler’s ally in starting WWII with the attack on Poland in September 1939. Unlike VOA journalists, Murrow cultivated contacts with democratic governments in exile in London and used their information about Stalin’s atrocities and plans for imposing Soviet-style Communism on Eastern Europe. Their information about Stalin being a mass murderer and about his contempt for all democratic values was absolutely true, but it was rejected out of hand by the wartime Voice of America as “anti-Soviet and anti-Communist propaganda.” The Soviet sympathizer who was the creator and writer of the first VOA news bragged about it in his memoir, appropriately titled Being Red.

The Voice of America’s most important World War II first-line journalist, pro-Soviet propagandist, and chief news writer in 1943, now almost completely erased from VOA’ history except for his memoirs, a few old interviews, a biography by Gerald Sorin, and previously classified U.S. government documents, was no other than Howard Fast, the best-selling author, member of the Communist Party USA from 1943 to 1956, and recipient of the 1953 $25,000 Stalin Peace Prize. Having given him the award which would have been worth over 235,000.00 in today’s dollars, the Soviets had to have been rather pleased with his past journalistic work for the Voice of America and his later reporting for the Communist Party newspaper The Daily Worker.20

In his 1953 testimony before a congressional committee, Fast claimed memory lapses and took advantage of imprecise questions to avoid describing his job as the Voice of America chief news writer. He had no problems recalling this information for his Being Red memoir, published in 1990. Gerald Sorin’s biography of Fast, Howard Fast: Life and Literature in the Left Lane, leaves no doubt that he played a key role in writing news for Voice of America broadcasters, many of whom were Communists.

“Fast wrote concise, dramatic pieces for broadcast, which were read by actors transmitting via BBC into Nazi-dominated Europe. … Eighteen of the twenty-three actors available for narration were Communists.21 Fast was not just ‘impressed’ by them, he said, but ‘overwhelmed’ by his associates ‘knowledge’ and ‘sensitivity’.”22

As he continued to write VOA news, Fast had hoped that he would be transferred to North Africa, where new medium-wave radio transmitters were being constructed. Once they became operational, his job of writing radio news in New York would be eliminated. He received, however, bad news from new VOA director Louis G. Cowan that the State Department has refused to give him a U.S. passport for travel abroad because it suspected him of having strong Communist Party connections. The same thing happened to John Houseman, which forced him to resign, but Cowan apparently did not want Fast to leave and offered him a job as a writer of propaganda pamphlets. According to Fast, Cowan also told him that the FBI had unmasked several card-carrying Communists on the Hungarian Desk, the German Desk, and the Spanish Desk. Fast was angry, declined the new job offer, and resigned to become active in the Communist Party and pursue his journalistic and literary career outside the U.S. government. Louis G. Cowan also held radically leftist views, and pro-Soviet propaganda continued in VOA broadcasts under his directorship during the war. On January 21, 1944, he wrote a glowing recommendation letter for Howard Fast, the future recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize, in which he stressed that accepting his resignation was “pure compliance with your wish — not at all what we want.”

“…what a fine job you have done for this country, the OWI, and the Radio Bureau [the Voice of America] in particular….Please accept my own sincere thanks and with that the gratitude of an organization and a cause well served.23

Louis G. Cowan ended his letter to Howard Fast with a note that he was being grateful for his service at the Voice of America, not only on his behalf but also on behalf of Office of War Information Director Elmer Davis, Overseas Bureau directors Robert E. Sherwood and Joseph Barnes, and former VOA Director John Houseman. Many people at the agency “have been inspired by your sincerity and your achievement,” Cowan added. Josef Stalin had to be also among those pleased with Howard Fast’s performance at the Voice of America.

Long after Howard Fast had left VOA, he became a victim of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communist witch-hunt, but the blacklisting by Hollywood film studios, as well as his three-month prison sentence for contempt of Congress for refusing to provide names of members of a Communist front organization, were not directly related to his World War II work at the Voice of America. At that time, VOA was only of minor interest to Senator McCarthy. By the early 1950s, real Communists were long gone from VOA, and he was chasing ghosts, mostly at the State Department. McCarthyism was, however, a shameful episode in American history which claimed many innocent victims. If they did not work as foreign agents, writers, and journalists should not have been blacklisted, but Howard Fast’s support for Stalin and Communism at the Voice of America deserved to be more fully investigated and exposed instead of being hidden by VOA officials and friendly journalists.

An appropriate punishment would have been exposure and moral condemnation of Fast and Houseman as a warning to future VOA broadcasters and radio listeners. Unfortunately, this did not happen. Fast’s blacklisting did not last long, and he quickly resumed his successful writing and publishing career. Meanwhile, millions of East Europeans, to whom Fast had tried to sell in VOA broadcasts the image of Stalin as a freedom-loving democrat, remained under brutal Soviet rule and a failing socialist economy for several more decades.

Fast eventually left the Communist Party in 1957, one year after Khrushchev revealed Stalin’s crimes, but he remained unapologetic about his promotion of Soviet “news” in VOA’s World War II broadcasts. His memoir Being Red, published in 1990, is a testimony to his journalistic naïveté, profound arrogance, and ability to manipulate readers into believing that to fight Fascism one had to become a Communist. For a journalist, he was supremely naive. In a 1998 radio interview, he described how staff members of the Communist Daily Worker cried when they read Khrushchev’s speech for the first time:

“And we heard this speech, and many of us wept. Because we did not know, and would not believe, the truth about the Soviet Union.

We had erected a Socialist state to our beliefs and to our dreams, and this for us was the Soviet Union.”24

According to Fast, there was no third way between Fascism and Communism, but even while he was still writing news for VOA, American labor unions supported by the progressive wing of the Democratic Party stopped their collaboration with the Office of War Information over complaints that pro-Soviet Communists were in charge of the VOA programs. The AFL-CIO, which refused to have anything to do with a Communist like Howard Fast, was hardly a fascist organization.25

Even after leaving the Communist Party, Howard Fast was largely unrepentant and insisted that while at VOA he knew very little about Stalin and the Soviet Union. “We were a party of the United States,” Fast wrote about the Communist Party USA, failing to mention that for decades the Party’s leadership was receiving money from Moscow. In the 1990s, he still showed great pride about his key role as the first chief writer of VOA news, promoter of Russian propaganda via the Soviet Embassy in Washington and censor of “anti-Soviet and anti-Communist” information. It happened to be true information about Stalin’s genocidal crimes, such as the deaths of thousands of children deported with their parents to the Soviet Gulag. Other true news kept out of VOA broadcasts were the brutal executions of thousands of prisoners of war in Soviet captivity. In Being Red, Fast proudly declared that he had kept such information out of VOA broadcasts.

“As for myself, during all my tenure there [VOA] I refused to go into anti-Soviet or anti-Communist propaganda.”26

Fast also condemned post-war U.S. government efforts to stop further Soviet aggression and to counter Soviet propaganda. These actions included the creation of Radio Free Europe (RFE) and Radio Liberty (RL) to broadcast uncensored news and commentary to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, but Fast wrote that Americans were also being targeted by the U.S. government.

“…starting with the end of World War Two, the American establishment was engaged in a gigantic campaign of anti-Communist hatred and slander, pouring untold millions into this campaign and employing an army of writers and publicists in an effort to reach every brain in America.”27

In fact, because of the abuses by the Office of War Information in attempting to spread Soviet propaganda not only abroad through Voice of America broadcasts but also to propagandize directly to Americans, the U.S. Congress passed the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act to restrict the distribution of VOA and State Department programs in the United States. The Smith-Mundt Act also imposed much stricter security clearances for Voice of America staff.

Howard Fast was not alone in his selective use of facts to promote Communism and Soviet interests. He had a lot in common with the infamous pro-Soviet New York Times reporter and Pulitzer Prize winner Walter Duranty who for years while reporting from Moscow hid from Americans the truth about the Stalinist genocide in the Soviet Union. Duranty’s Pulitzer Prize was never revoked. As for Fast, he was quite happy to have received the Stalin Peace Prize.

“The International Committee, headed by [French poet and longtime Communist Party member] Louis Aragon, awarded me the Stalin International Peace Prize. This consisted of a beautiful leather-bound diploma case, a gold medal, and $25,000 [about $235,000 in 2019 dollars], which revered our slide to poverty. …and considering the hundreds of thousands of my books printed in the Soviet Union, for which no royalties had ever been paid, the $25,000 aroused no guilts for undeserved gratuities.”28

Considering that Howard Fast later received a handsome sum of money from Moscow, the early VOA radio news programs he prepared during the war must have been indeed well received by the Kremlin and by Communists everywhere. They also did tremendous harm to the truth and to millions of listeners to early VOA radio broadcasts. The damage of Soviet propaganda being forced at U.S. taxpayers’ expense by the Voice of America upon millions of wartime and post-war victims of Stalin’s rule over Eastern Europe was officially acknowledged and condemned by a bipartisan committee of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1952, but that rebuke has also become part of the forgotten history.29

Unsurprisingly, Howard Fast’s VOA newscasts were not well received by refugees fleeing Communist repression, including family members of Gulag prisoners lucky enough to be alive and able to listen to VOA broadcasts during the war, mostly those who had escaped from under Nazi and Soviet occupation. Howard Fast had helped to spread Soviet propaganda lies to wives, children, and other family members of thousands of military officers and other Polish POWs secretly executed on the orders of Stalin and the Soviet Politburo in the 1940 Katyn Massacre. Anti-Nazi and anti-Communist Yugoslav partisans, democratic French, Italians, Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, Romanians, Bulgarians, Greeks, and anybody else who understood the danger of Communism and Soviet totalitarianism would have been equally appalled by Fast’s promotion of Stalin in VOA broadcasts as a friend of democracy and a guarantor of peace and progress. Even after Howard Fast was gone from VOA, its broadcasts continued to reflect Soviet propaganda for a few more years, as they constantly did during World War II. A Polish journalist and radio broadcaster Czesław Straszewicz, who was in London during the 1944 anti-Nazi Warsaw Uprising, recalled in 1953 in an article published in Paris:

“With genuine horror we listened to what the Polish language programs of the Voice of America (or whatever name they had then), in which in line with what [the Soviet news agency] TASS was communicating, the [1944] Warsaw Uprising was being completely ignored.”30

The ideological blindness and journalistic shortcomings of early VOA officials and broadcasters were profoundly dangerous. Supreme Allied Commander and later U.S. President General Dwight D. Eisenhower accused them of “insubordination” for endangering the lives of American soldiers with their pro-Communist and pro-Soviet propaganda.31 Both Howard Fast and his patron, first VOA Director John Houseman, himself a Communist sympathizer who hired Communists for key VOA broadcasting positions, eventually were forced to resign quietly from their Voice of America jobs under pressure from the FBI, the U.S. Army Intelligence and the State Department, but other Communists and Soviet sympathizers remained in charge of VOA and VOA news for several more years. A Slovak source told the CIA after the war that VOA’s pro-Soviet propaganda may have caused the death of some people in Czechoslovakia who chose to return from the West believing after listening to VOA broadcasts that they will not be harmed by the Communist regime.32It was not until a few years after the war, when the Voice of America came under renewed bipartisan criticism from the U.S. Congress, that personnel and management reforms were initiated to change its programming. These reforms eventually turned VOA into a somewhat effective tool in exposing Soviet and communist propaganda in the later years of the Cold War.

It is both possible and highly desirable for the United States to communicate effectively with the world through various forms of media outreach and public diplomacy, but to avoid the repetition of the same past mistakes, the true history of the Voice of America deserves to be much better known to more individuals in key U.S. government positions.

Current VOA managers and reporters, and anyone else working for the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM), should read Howard Fast’s memoir and the State Department’s previously classified World War II memos calling for the removal U.S. government officials and journalists suspected of promoting Russia’s interests when they came in conflict with America’s interests and values. This would also be a useful reading for the State Department’s Public Diplomacy and Global Engagement Center staff and anyone else looking at VOA’s current program content to Russia, China, and Iran amid concerns that it has been corrupted by hostile propaganda and pressure from foreign regimes. According to a report of the Working Group on Chinese Influence Activities in the United States prepared by the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and the Center on US-China Relations at Asia Society in New York, “starting in the first decade of the 2000s, the Chinese embassy in Washington, DC, and the leadership of VOA’s Mandarin service began an annual meeting to allow embassy officials to voice their opinions about VOA’s content.” See: https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/chineseinfluence_americaninterests_fullreport_web.pdf .The Hoover Institution and Asia Society report also said that “VOA personalities have hosted events at the embassy,” and one of VOA’s TV editors “even publicly pledged his allegiance to China at an embassy event.” The report cited “interview with VOA staff” as a source of this piece of information.

The American Foreign Policy Council (AFCP) study commissioned by the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) in 2017 found that the Voice of America and Radio Farda within Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL), both reporting to the BBG, which was later renamed as the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM), practiced substandard journalism, resorted to censorship and repeated Iranian regime propaganda. The study concluded: “This dynamic, on the whole, perpetuated to audiences the appearance of pro-regime propaganda, rather than objective reporting, on the part of both the VOA and Farda.” See: https://www.bbg.gov/wp-content/media/2011/11/AFPC_Persian-Language-Broadcasting-Study_synthesis-report.pdf.

Another independent BBG study done in 2011 found that the Voice of America Russian Service website had a “pro-Putin bias.” See: http://bbgwatch.com/bbgwatch/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Rudenskiy.pdf.[/ref]

The enslavement by Stalin’s Russia of millions of people at the end of World War II proved that concealing the truth in the battle for the truth, and lying about it, can lead to disastrous results.

TESTIMONY OF HOWARD FAST

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 13, 1953

U.S. Senate

Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations

New York, NY.

The subcommittee met, pursuant to Senate Resolution 40, agreed to January 30, 1953 at 10:30 a.m., in room 2804, U.S. Court House Building, Foley Square, New York City, Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, chairman, presiding.

Present: Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, Republican, Wisconsin;

Senator Henry M. Jackson, Democrat, Washington;

Senator Stuart Symington, Democrat, Missouri.

Present also: Roy Cohn, chief counsel;

Donald Surine, assistant counsel;

David Schine, chief consultant;

Henry Hawkins;

Julius W. Cahn, counsel, Subcommittee Studying Foreign Information Program of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.

TESTIMONY OF HOWARD FAST (ACCOMPANIED BY HIS COUNSEL, BENEDICT WOLF)

Mr. Fast. Howard M. Fast.

Mr. Cohn. And your address?

Mr. Fast. 43 West 94th, New York.

Mr. Cohn. And what is your occupation?

Mr. Fast. A writer.

Mr. Cohn. You are a writer. Are you the author of Citizen Tom Paine among other works?

Mr. Fast. I am.

Mr. Cohn. Mr. Fast, are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist party?

Mr. Fast. I must refuse to answer that question, claiming my rights and protection under the First and Fifth Amendments

to the Constitution of the United States.\9\

—————————————————————————

\9\ In his memoirs, The Naked God: the Writer and the Communist Party (New York: Praeger, 1957), and Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1990), Fast wrote that he had joined the Communist party in 1943 or 1944 and resigned from the party in 1956.

—————————————————————————

Mr. Cohn. Are you now a member of the Communist party?

Mr. Fast. I refuse to answer that question for the same reasons I stated before.

Mr. Cohn. When did you write Citizen Tom Paine, Mr. Fast?

Mr. Fast. When did I write it? Or when was it published?

Mr. Cohn. I am sorry. When was it published? That is the date I want.

Mr. Fast. It was published, I believe, in April of 1943.

Mr. Cohn. And at the time it was published, were you a member of the Communist party?

Mr. Fast. I must refuse to answer that question also on the basis of the rights guaranteed to me by the First and Fifth Amendments to the Constitution.

Mr. Cohn. During the period of time you were writing the book, while you were preparing the material and writing the book, were you a member of the Communist party?

Mr. Fast. I refuse to answer that question, for the same reasons I stated before.

The Chairman. Just so the record will be clear and that all the members and the staff understand, it should appear that the section of the Constitution to which the witness refers is the section which gives him the right to refuse to answer if he feels his answer may incriminate him.

Mr. Cohn. Now, are you the author of any other books?

Mr. Fast. Yes.

Mr. Cohn. How many, Mr. Fast?

Mr. Fast. I don’t know offhand.

Mr. Cohn. Would you give us an approximation, please?

Mr. Fast. I will name those of the books I can remember.

Mr. Cohn. Would you do that?

Mr. Fast. Place in the City, Conceived in Liberty, The Last Frontier, The Unvanquished, Citizen Tom Paine, Freedom Road, The American, Patrick Henry and The Frigate’s Keel. Do you want me to try to go through all of them?

Mr. Cohn. Just continue on.

The Chairman. As many as you can remember.

Mr. Fast. Clarkton, The Children.

The Chairman. Well, those are the ones you recall?

Mr. Fast. My Glorious Brothers, The Proud and the Free, Spartacus. And that isn’t the end of it.

Mr. Cohn. Mr. Fast. I would like to ask you the same question addressed to each one of these books which you have mentioned. At the time you wrote each one of these books, were you a member of the Communist party?

Mr. Fast. I would refuse to answer that question on the same grounds that I stated before.

Mr. Cohn. Would you refuse to answer that as to each and every one of those books enumerated, as well as to any other book you have written?

Mr. Fast. Let me make my position plain. I will claim this privilege guaranteed to me under the Fifth and the First Amendments to the Constitution of the United States. In terms

of any question which makes reference to the Communist party or organizations or periodicals cited in, let us say, the House Committee on Un-American Activities’ list of so-called subversive organizations.

Mr. Cohn. Do you know a man by the name of Bradley Connors, C-o-n-n-o-r-s?

Mr. Fast. I don’t recollect the name.

Mr. Cohn. I see. Do you know anybody currently employed in the State Department having any connection with policy?

Mr. Fast. Do you mean have I met anyone? You see, this is such a broad question, and I don’t want to risk any chance of answering it incorrectly. Offhand, I can’t think of anyone I know who is employed in the State Department, policy-wise or otherwise.

Mr. Cohn. Very well. Now, my next question is: Have you ever been convicted of a crime?

[Witness consults with counsel.]

Mr. Fast. Do you include a misdemeanor as a crime?

Mr. Cohn. I would include a misdemeanor as a crime.

Mr. Fast. I have, yes.

Mr. Cohn. And what was it, and when?

Mr. Fast. I was convicted of contempt of Congress in the federal court in Washington–when? My lawyer probably remembers the date better than I do.

Mr. Cohn. And about when was that?

Mr. Fast. I believe it was 1947.

Mr. Wolf. I think so. I am not sure.

Mr. Fast. Possibly about May of 1947.

Mr. Cohn. What sentence did you receive?

Mr. Fast. Three months and a fine.

Mr. Cohn. Did you serve that term in jail?

Mr. Fast. Yes.

Mr. Cohn. Have you ever been arrested for any crime?

The Chairman. Any other besides the one you mentioned.

Mr. Fast. Well, arrest. Arrest in that sense? I don’t think so.

Mr. Cohn. In any sense, have you ever been arrested?

The Chairman. Either arrested or convicted.

Mr. Fast. I have been brought in on one occasion by an officer, for crossing a white line in Briarcliff.

The Chairman. You could not know of any other crime of which you were convicted?

Mr. Fast. I was never on trial at any other occasion that I can remember.

The Chairman. Have you ever been consulted by anyone in the Voice of America?

Mr. Fast. Now, I want to clarify this: You see, I know from the papers that this is a hearing on the Voice of America. I read that. When you say, “The Voice of America,” what do you mean?

The Chairman. Well, we mean just that, the Voice of America. Let us make it broader. Have you ever been consulted by anyone in regard to any of our government information programs, regardless of whether it is the Voice of America or any other government information program?

Mr. Fast. Consulted by someone?

The Chairman. Yes.

Mr. Fast. Yes, I have.

The Chairman. Who have you consulted with?

Mr. Fast. When you use the term “consulted,” I presume you mean discussed this question with me?

The Chairman. Yes, using it in its broadest sense, any discussion you have had with any of the people over in any of the information programs.

Mr. Fast. Various people who were a part of the Office of War Information, overseas radio division.

The Chairman. Will you name some of them? Name all those you can remember.

[Mr. Fast confers with his counsel.]

Mr. Fast. Before I do that, I want to just clarify my position there. I worked in the Office of War Information.

The Chairman. How long did you work in the OWI?

Mr. Fast. I worked there, I believe, from November of 1942, from about November of ’42, to about November of ’43. That is a long time ago. My memory isn’t too certain on that. But I believe about then.

The Chairman. In other words, about a year?

Mr. Fast. About a year.

The Chairman. And I assume your answer would be the same as it was previously, but I will ask you the question anyway. At the time you were working in the OWI, were you a member of the Communist party?

Mr. Fast. I would have to refuse to answer that question for the reasons previously given.

The Chairman. Who hired you in the OWI Who recruited you?

Mr. Fast. What do you mean “recruited”?

The Chairman. Well, would you just give us a description of how you happened to get the job in OWI?

Mr. Fast. I want to again preface my remarks by saying this is ten years ago, and I am not too clear. It is over ten years ago, and my memory would play false with me. But as I remember it, I was at that time living in Sleepy Hollow, New York, with my wife, the same one I am married to now, and I received my draft notification, and this gave my wife and myself reason to believe I would be drafted within the next couple of months. So we closed up our house in the country and moved into town. And I knew some people then who were working at the Office of War Information, and I dropped up to see them, and I said—-

Senator Jackson. Whom did you know?

Mr. Fast. Let me finish this, and I will go to that–to fill in this interim period, I would like to do some work with the Office of War Information, and, “How do I go about applying?” And I think I was told how I go about applying, and I simply applied. This, I think-I am very unclear about it because it was so long ago.

The Chairman. Mr. Jackson asked the question: Whom did you know there and whom did you consult?

Mr. Fast. Excuse me.

[Mr. Fast confers with his counsel.]

Mr. Fast. You want to know who I knew before—-

The Chairman. Yes. You told us a minute ago that after your draft notice came through, you knew some people in the OWI, and you went to see them and discussed with them the possibility of getting in the OWI. The question Mr. Jackson asked was: Who were those people?

Mr. Fast. Again, I must preface this by saying my memory is unclear, due to the length of time. I believe I knew, or lese I knew by reputation, and he knew me by reputation, Jerome Weidman, the writer. Most likely by reputation. I don’t know whether I had ever met him before, as I remember it.

The Chairman. Jerome Weidman was holding what position in the OWI?

Mr. Fast. I don’t know, because this area of the Office of War Information into which I was brought to work, I remained in only a very short time, possibly only three weeks, and then I was transferred to the overseas radio division.

The Chairman. You said he knew you by reputation. At that time, did you have a reputation as a Communist writer?

Mr. Fast. I must refuse to answer that, too, on the same grounds stated before. But another point: Aren’t you asking me what another person thought?

The Chairman. You said he knew you by your reputation. I want to know what that reputation was. Was that your reputation as a Communist writer? And I am going to direct you to answer that question. You understand, Mr. Fast, that we are not asking you to pass upon whether that reputation was an earned reputation or not. Many people have a reputation which they do not deserve. The question is: What was the reputation?

Mr. Fast. You are asking me an exceedingly ambiguous question. You are asking me what my reputation was and I could not poll a reputation. In so far as I was aware of it at the time, my reputation—-

[Mr. Fast confers with his counsel.]

Mr. Fast [continuing]. My reputation was such as to cause me now, when I refer to it, not to mean certainly my reputation as a Communist writer. In other words, when I refer to my reputation, that Weidman knew me by, I was not referring to a reputation as a Communist writer.

The Chairman. I am not asking you at this time whether you were a member of the Communist party, but were you generally considered, in the writing field, in other words, did you have the reputation at that time, of being a Communist writer?

Mr. Fast. I think you would be more suited to answer that question than I would, don’t you?

The Chairman. Except that I am not under oath and not on the witness stand.

Mr. Wolf. That is an advantage sometimes.

Mr. Fast. I really can’t say. I just don’t know. I couldn’t say under oath, with any sense of clarity, what my reputation was eleven years ago. It was a reputation–I will say this–it was a reputation which was spelled out by Time magazine when they reviewed my book, The Unvanquished, and said that The Unvanquished was one of the finest American sagas to come out at the beginning of the war. Conceived in Liberty was reviewed everywhere throughout the country.

The Chairman. Let us stick to this—-

Mr. Fast. I am talking about reputation. Just a word or two more, and I will try and establish a little reputation.

The Chairman. You may have a perfect right to answer every question in the way you think you should answer, but as we hit a certain point I may want to question you about it. Now, who reviewed the book for Time magazine?

Mr. Fast. I have no idea. I don’t remember. But you can find in the files of Time magazine the review I referred to. No, not Time magazine. Newsweek magazine; I am sorry. Make that correction.

The Chairman. I understand your answer to be that you do not know whether your reputation at that time was as a Communist writer. Either you do or you do not know that you had such a reputation.

[Mr. Fast confers with his counsel.]

Mr. Fast. As far as I know, that was not my reputation.

The Chairman. Did you know that Jerome Weidman was a member of the Communist party at that time?

Mr. Fast. I would have to refuse to answer that question, for the reasons stated before.

The Chairman. Who were these other people that you said you knew in OWI at that time?

Mr. Fast. You see, it is very hard for me to separate those I knew then from those I came to know in the later period. I was not acquainted with any considerable number. There must have been one or two others besides Weidman.

The Chairman. I am not trying to pin you down to anything you cannot remember, Mr. Fast. I know that, as you say, it is difficult to say at this time who you knew ten years ago and who you might have gotten to know eight years ago. But in answer to a previous question, you said you knew some people at

OWI at that time that you went to them and consulted with them.

Mr. Fast. I went up to OWI itself. I went up to this office.

The Chairman. Outside of this man Weidman, who else did you consult with?

Mr. Fast. You see, I couldn’t swear to that. At that time, when I went up to their office, I couldn’t swear whether I spoke to a man called Ted Patrick, who I believe was the head of this particular publications department. But as I say, it is vague, because I remained a very short time in this department, and my knowledge of the department is far vaguer than my knowledge of the department I—-

The Chairman. Did you know Owen Lattimore?

Mr. Fast. To my recollection, as far as I can recollect, I don’t think I ever met him; although it may be that I have, because I met many people at that time, and it did not leave a very lasting recollection.

The Chairman. In other words, as well as you can recollect, you have never met Owen Lattimore?

Mr. Fast. As well as I can recollect. It may be I was casually introduced to him as I passed through that office, but it doesn’t stand out very strongly in my recollection.

The Chairman. Did you review any of his books and/or did he ever review any of your books?

Mr. Fast. I don’t think I ever reviewed any books of his. I say, “I don’t think,” because in a long career, I have reviewed a great many books. And I also don’t think he ever reviewed a book of mine.

The Chairman. Is it correct that in the writing field it is the accepted practice for one Communist to review the writings of another, and he in turn will review the writings of the men who review his book? Do you follow my question? In other words, let us say that you and I are both Communists, and we are writers. Is it the accepted practice that I would be reviewing your books and you in turn would be reviewing mine?

Mr. Fast. I think I would attempt to invoke the privilege of the Fifth Amendment and refuse to answer that question.

The Chairman. Do you know which of your books were purchased by any branch of the government?

Mr. Fast. This is also a complicated question to try to answer. Why don’t you make your question specific? It is a very general question, as it now stands.

The Chairman. Well, do you know of any of your books that were purchased by any branch of the government? That is what I want to know.

Mr. Fast. Well, you see, the reason I am slow to answer that is this: that according to my knowledge of my books—-

The Chairman. If you have difficulty with that question, you can tell we why, and I will try to simplify it.

Mr. Fast. What is that?

The Chairman. I say if you have difficulty with that question, tell me why and I will try to simplify it.

Mr. Fast. Well, there was the Armed Service Books Project. You may remember the books they had overseas with the two columns of type in them. I could not say now whether these books were published by the government or a private agency. It may have been a semi-official agency of the government. They were distributed through the army. Of those books, the armed service editions, the following of my books I believe became a part of the series: The Unvanquished my novel about George Washington, Patrick Henry and the Frigate’s Keel, and Freedom Road. I believe those three books, although, again, it has been so many years since I have looked at this. Now, there was another project—-

The Chairman. You think those were the only three purchased by the armed services?

Mr. Fast. Printed in their editions. I think so. Now, there was another project which the State Department engaged in more directly.

Mr. Wolf. If I may clarify one thing, Senator, with regard to the previous question there may have been a misunderstanding. You mentioned something about “purchased by the armed services.” I think Mr. Fast made it clear that none of them were put out by the armed services.

The Chairman. It was an armed services project. I understand your answer, Mr. Fast, to be that you do not know who purchased the books, who put them out. You do know this was an armed services project?

Mr. Fast. This was a big reprint operation, which you probably know more about than I do. At the time I knew little about it, and now it is vague. They put out millions of books, as I remember.

The Chairman. Then, going on to the State Department project?

Mr. Fast. Yes, on this State Department project–now, I recollect clearly the size and appearance of the books, but I don’t know too much about them at this date. The State Department took certain books of mine, possibly only Citizen Tom Paine, and reprinted them in many languages. I am not certain of the purpose; perhaps to stock libraries with.

The Chairman. Do you remember, roughly, the date of this?

Mr. Fast. I couldn’t guess. I would say maybe ’44 or ’45, but that is just the roughest kind of a guess.

The Chairman. When did you write Citizen Tom Paine?

Mr. Fast. Citizen Tom Paine was published, as I said before, in April of 1943.

The Chairman. Was it 1944 or 1945 that the State Department reprinted a very sizable number of copies of that book and sent them throughout the world?

Mr. Fast. Whether there was a sizable number, I don’t know. I have no recollection about any of the details of the reprinting of that book.

The Chairman. You do know they translated it into many different languages?

Mr. Fast. Yes, I know that, because I have in my files at home I believe Italian and French editions.

The Chairman. And what income did you get from that operation?

Mr. Fast. I have no recollection of that.

The Chairman. How much money would you say you received either directly or indirectly, from the government, any government agency or any semi-official government agency, over the past ten years?

Mr. Fast. That would be very difficult for me to say.

The Chairman. Give us a rough guess, if you can.

Mr. Fast. Well, if I worked a year at the Office of War Information–I believe my pay there was somewhere around eight thousand dollars a year, although I couldn’t swear to it.

[Mr. Fast confers with his counsel.]

Mr. Fast. I would guess that the total money received over the period you remarked about would be somewhere in the neighborhood of nine or ten thousand dollars.

The Chairman. In other words, a thousand or two thousand dollars besides your salary?

Mr. Fast. Now, wait a minute. I must amend that. I don’t know. I have no recollection of how much money I was paid from these books. Whether that money came from the State Department, I don’t know. This might change it somewhat. I also don’t know how much I was paid for the armed services editions, and whether that could be included as a part of the answer to such question, whether it was a private agency or a government agency.

The Chairman. In other words, if you exclude the books that the State Department put out, and exclude the books put out under this armed services project, you had an income of about a thousand dollars or two thousand dollars from other government sources, other than your salary?

Mr. Fast. I think so.

The Chairman. Will you give us the source of that thousand or two thousand?

Mr. Fast. You know, I am estimating very roughly when it comes to figures, because I could not check these. I worked during the war on a special project for the Signal Corps.

The Chairman. Classified, was it?

Mr. Fast. What do you mean by “classified”?

The Chairman. Listed as either secret, confidential, or restricted.

Mr. Fast. I don’t think so. It consisted of preparing for them a script of a film which would portray certain scenes from the landing of the Pilgrims to modern America, in terms of a historical survey of the United States.

The Chairman. Did you do any work for the Voice of America?

Mr. Fast. You mean the OWI?

The Chairman. No, the Voice of America, the VOA?

Mr. Fast. I can’t seem to remember any. I can’t seem to remember any project after resigning from the Office of War Information that I did for the Voice of America.

The Chairman. Did the Voice of America discuss with you the possibility of using your book, Citizen Tom Paine?

Mr. Fast. They might have. You see, my books were used in so many ways at that time. I don’t really remember all of it. For instance, The Unvanquished was put on records, read by Eleanor Roosevelt, for the blind. My books or forms of my books or dramatizations of my books were made in Europe, records were made of them, all sorts of things, because they suited a need at the time. So I just couldn’t keep track of them and wouldn’t know.

The Chairman. Were you a social acquaintance of Eleanor Roosevelt?

Mr. Fast. I wouldn’t say that, no. That would be unfair. I met her only once, I believe.

The Chairman. You met her only once?

Mr. Fast. I believe so.

The Chairman. Roughly when was that?

Mr. Fast. I believe I met her in 1940.

The Chairman. Was that at the time she was considering putting out her book?

Mr. Fast. What book?

The Chairman. The one you just mentioned.

Mr. Fast. I don’t know.

The Chairman. You see, I do not happen to be a reader of your books, so when you name them, I have difficulty.

Mr. Wolf. You missed something good.

Mr. Fast. If you are interested in the history of the United States, it might be important to read them.

The Chairman. The question was: Did you see her at the time she was considering this?

Mr. Fast. No, this project on The Unvanquished was done by one of these Institutes for Blind people, and I think she was simply gracious enough to offer her services free of charge to read the book aloud.

The Chairman. What was the occasion of your meeting with Mrs. Roosevelt?

[Mr. Fast confers with his counsel.]

Mr. Fast. I was along with a number of other people invited to the White House for lunch in late 1944.

The Chairman. Who were the other people?

Mr. Fast. Oh, I don’t remember. There were a great many people there.

The Chairman. Do you remember any of them?

Mr. Fast. I don’t know if I can certainly say I do remember any who were there. There were a number of people, but it is so long ago that I can’t say so-and-so was there. My wife was with me.

The Chairman. Do you remember whether any of the others were members of the Communist party?

Mr. Fast. I would have to refuse to answer that question too, for the reasons given before.

The Chairman. Was Joe Lash at that party?

Mr. Fast. I don’t know.

The Chairman. Do you know anyone in the State Department today who is a member of the Communist party?

Mr. Fast. I would have to refuse to answer that question for the reasons given before.

The Chairman. Do you know anyone in the Voice of America who is, as of today, a member of the Communist party?

Mr. Fast. I would have to refuse to answer that question also for the reasons stated before.

The Chairman. You started telling me of the projects in which you received money from the government other than your service in the OWI. I believe I interrupted you with some other questions. Will you proceed with your answer to that?

Mr. Fast. I think I mentioned the Signal Corps project. Now, you raise the question of the use of Citizen Tom Paine, and it strikes a vaguely familiar note, but I just couldn’t say “yes” or “no.” I might have received payment

from the government for various use made of various material in my books. I cannot at this date specify or recall exactly.

The Chairman. Would your books show that money you received from the government?

Mr. Fast. My own books?

The Chairman. Yes.

Mr. Fast. Oh, yes. Yes.

The Chairman. You will be ordered to produce those books, and we will give you sufficient time to do it.

Mr. Fast. Over what years?

The Chairman. What years would you suggest, Mr. Counsel?

Mr. Cohn. Well, when did you go with OWI?

The Chairman. Let us make it since 1940.

Mr. Fast. Now, as far as OWI is concerned, I don’t know whether that money—-

The Chairman. You will be ordered to produce the books.

Mr. Cohn. I think 1940 would be a good date.

The Chairman. From and including 1940 down to date.

Mr. Wolf. I will note a protest to this proceeding. I want that on record.

The Chairman. I would be glad to hear you on this.

Mr. Fast. I must state here I do not know how far back my books go.

Mr. Wolf. Unless there is some indication of the relevance of the books to the inquiry, the purpose of which is not yet stated on the record, as far as this particular hearing is concerned–first, with regard to the relevance, I have no way of telling whether this inquiry for what is, in effect, a

blanket subpoena is within the realm of proper inquiry of the committee. I notice that the committee is not asking for those books of Mr. Fast which deal with income received from the government, but is asking for all his books and records for a period of some twelve years.

The Chairman. May I say to counsel that I think you are correct that there is no right for the committee to get these books other than the books which show income from the government or from some semi-official agency or from some working in the government, and those will be the only part of your books we will order produced. Now, who hired you in OWI? Do you remember?

Mr. Fast. No, I couldn’t say who hired me originally.

The Chairman. Do you know who recommended you? Was it this fellow, Weidman?

Mr. Fast. No. I couldn’t even say that with any certainty at this time. I know I filled out an application, and I received a letter subsequently saying they were happy to have me come and work for them.

The Chairman. Do you know who you gave as reference at that time?

Mr. Fast. No, I don’t recollect.

The Chairman. Do you have a copy of your application?

Mr. Fast. I would doubt it. I would doubt that I made a copy at the time.

Mr. Cohn. Do you know Raymond Gram Swing?

Mr. Fast. I don’t think I do. I am not sure, but I don’t think so.

Mr. Cohn. Do you know Harold Burman?

Mr. Fast. I don’t recall knowing him.

Mr. Cohn. Arthur Kaufman?

Mr. Fast. I don’t recall knowing him.

Mr. Cohn. Robert Bauer, B-a-u-e-r?

Mr. Fast. I don’t recall knowing him. I may have met one or all of these people casually at one point or another, but their names don’t ring a bell.

Mr. Cohn. Norman Jacobs?

Mr. Fast. No, I don’t recall knowing him.

Mr. Cohn. A man named Baxt, B-a-x-t?

Mr. Fast. No, I don’t recall knowing him.

Mr. Cohn. Jennings Perry?

Mr. Fast. No, I don’t recall knowing him.

Mr. Cohn. I have nothing more at the moment, Mr. Chairman.

The Chairman. May I say to counsel that if your client cares to examine the transcript for typographical errors and correct those errors, he may do so. However, this is executive session, so we can’t send you the testimony. If you want to go over the record, you will have to come down to Washington.

Mr. Wolf. Yes. If we are informed when they will be ready for examination.I think there is one other thing that should be stated for the record.

The Chairman. First, let me say the transcript will be available Monday and thereafter. I would say that if you want to come down and check the record for errors, it should be done fairly soon, because the record may go to the printer. I don’t know. And after it once goes to the printer, you would be unable to make any corrections.

Mr. Fast, I understand that you desire to make a statement. If you make a statement, I would suggest that you make it full and tell why you make it.

Mr. Fast. I wish to make a statement of some of the facts surrounding service of the subpoena, and protesting the type of service as undignified in terms of this committee, unworthy of the government which this committee represents. At about ten o’clock my bell rang. I opened the door. There was a young man there. He said he had for Howard Fast a highly secret communication from “Al.”

I said, “Al who?”

He said, “Just from Al. Al said you would know.”

I said, “Al who? I don’t know any Al.”

He said, “Al. Are you Mr. Fast?”

At that point, having no notion that there was a subpoena involved, having not been told that he was in any way an official, I said, “No.”

He said, “Well, I will wait for Mr. Fast.”

I said, “Wait outside.” And I closed the door.

At about one o’clock in the morning following that, my bell rang. I went to the door. A voice said: “I am the assistant counsel for the House Committee on” or “for the Senate Committee on Operations, and I want to talk with you, Howard.”

I said, “My name is `Mr. Fast.’ ”

He said, “Okay, Howard. I just want to have a talk with you. Let me in.”

I said, “I have no need to let you in. You cannot demand that I let you in. I don’t know you from Adam. Beat it.”

He said, “No, I want to talk with you, Howard.”

I said, “Beat it, or I will call the police.”

At that point, he left. I called my lawyer. My lawyer advised me that legally I am within my rights in refusing to open the door at that hour of the morning to someone unless this person has a search warrant; whereupon, I went to bed. At about 1:30 there was a pounding on the door and a ranging of the bell, which woke my children and terrified them in the time honored Gestapo methods, and I came down there, and here was this offensive character again, and this time for the first time he stated that he had a subpoena with him.

The Chairman. Would you say they were the GPU type tactics or NKVD type tactics also?

Mr. Fast. I have read of these tactics in connection with the Gestapo. This is my choice of description, and this action I find offensive and unworthy of any arm of the government of the United States. I would have accepted service very simply

and directly the following morning. There was no need to go through that procedure.

The Chairman. We would like to get the complete picture of the attempt to service and the entire picture in the record.

Mr. Cohn. We will do that. You said you called your lawyer that night and he gave you advice as to your rights; is that right?

Mr. Fast. Right.

Mr. Cohn. You called me up yesterday, asking for an adjournment of your appearance today?

Mr. Fast. Yes.

Mr. Cohn. Didn’t you tell me you had not been able to reach your lawyer, that you needed more time, because it was Lincoln’s birthday and you couldn’t reach him, and you needed an adjournment?

Mr. Fast. My lawyer was out of town, down in New Jersey at his country home.

Mr. Cohn. Do you deny telling me you couldn’t reach your lawyer?

Mr. Fast. I don’t recollect whether I told you I couldn’t reach my lawyer, or my lawyer was out of town, or it was Lincoln’s birthday and lawyers were not available.

Mr. Cohn. The fact was that you had talked to your lawyer the night before?

Mr. Fast. No, I talked to his partner, Martin Popper, at his home.

Mr. Cohn. He is your lawyer, is he not?

Mr. Fast. He is not my lawyer. Mr. Wolf is my lawyer.

Mr. Cohn. You have now told us you did consult with a lawyer the night before. Isn’t that a fact?

Mr. Fast. I didn’t consult with a lawyer about a subpoena. I didn’t even know there was a subpoena involved.

Mr. Cohn. Do you deny—-

Mr. Fast. In fact, when I spoke to Mr. Popper, I said: “What do you think it is?” And he said, “I think it is a nuisance and nothing else, and if it continues, call the police.” I was not told there was a subpoena involved.

Mr. Cohn. Now, when the gentleman returned to serve you with the subpoena, was he accompanied by anyone?

Mr. Fast. A policeman. That is why I opened the door and accepted the subpoena.

Mr. Cohn. Mr. Chairman, I think other witnesses can bring out the rest of the facts connected with the service. What time do you say this was, Mr. Fast?

Mr. Fast. The first call was probably shortly before one o’clock in the morning, a few minutes before one, and the second time he came back it was about half past one in the morning.

Mr. Cohn. You are quite sure of that, about half past one in the morning?

Mr. Fast. I would think so.

The Chairman. The first contact you had was about ten o’clock at night. Is that right?

Mr. Fast. Yes, but I did not know he had any connection with the committee. I told you exactly what he said, in the hearing of my wife.

The Chairman. And you talked through the door?

Mr. Fast. No, no. I opened the door. People know where I am, and I open the door. I just don’t like to open it at one-thirty in the morning, to someone who is pounding on it.

The Chairman. I am talking about the ten o’clock meeting. Did you open the door then?

Mr. Fast. Yes.

The Chairman. And you said you were not Howard Fast?

Mr. Fast. Yes. Because I was highly suspicious and a little nervous and a little frightened. He said he was from Al.

The Chairman. When he returned and said he was the assistant counsel for this committee, did you open the door again?

Mr. Fast. No.

The Chairman. Did you talk through the door?

Mr. Fast. Right.

The Chairman. And I am just rather curious to know why you refused to open the door when the assistant counsel for this committee said be wanted to talk to you.

Mr. Fast. Because, as I said to him, I said, “If you have anything to say to me, say it during the day. Don’t come at one o’clock in the morning and tell me you want to have a conversation with me. That is outrageous.”

The Chairman. Well, he first started to serve the subpoena—-

Mr. Fast. He did not state he had a subpoena to serve me with.

The Chairman. Let me ask the chief counsel: Do I understand one of your investigators started to serve the subpoena at ten at night, and finally by taking a policeman to the home of Mr. Fast, he accomplished the service about one thirty in the morning?

Mr. Cohn. The times are somewhat wrong,

Mr. Chairman. There is a long history of attempts to locate Mr. Fast. I think we can put that in through other sworn testimony.

The Chairman. Mr. Fast, you are notified that you are still under subpoena, subject to recall.

Mr. Fast. That states nine o’clock in the morning. It states the subpoena was served on me at nine o’clock in the morning. I can’t understand why the man did that.

The Chairman. You are now informed that you are under subpoena subject to recall. We will notify your attorney when we want you to return. When do you want the records produced? I assume it will take Mr. Fast some time to get those records. Let me ask you: How much time would you consider a reasonable amount of time?

Mr. Wolf. They are pretty old, you know.

Mr. Cohn. We need them as soon as we can get them, as the Chairman indicated.

Mr. Fast. What happens if I don’t have complete records?

Mr. Cohn. That is an issue we can discuss then.

Mr. Wolf. Would a week or ten days be enough?

Mr. Fast. I think so. Do I have to appear with the records?

The Chairman. We can notify your lawyer. I assume so. You will have to appear, I assume. You told us a few minutes ago that you had very complete records, and you indicate now—-

Mr. Fast. I must make one correction.

The Chairman. Let me finish, please–that you kept very complete records. That is what you said. You indicate now you may not have saved some of those records. For that reason we want you under oath when you produce the records. We want to question you about them. We will try in your case, as in the case of every witness, to set a date that will not create an undue hardship upon you or upon your attorney. I would suggest that you be prepared within a week to produce the records. We will not set a specific date now, but Mr. Cohn will contact your attorney.

Mr. Cohn. I know his partner, Mr. Popper, from past occasions.

Mr. Cahn. Mr. Chairman, may I just ask one question, which was not quite clarified. I believe that counsel or the chairman had previously asked you, Mr. Fast, as to any acquaintanceship which you might have with individuals who are now or have been participants in the Voice of America radio operation or in other phases of the government’s information program, and I would like to resume that questioning now and ask: Have you within the past year or

two years had any discussion of any nature with any individual whom you knew personally to be an official of the United States government or an employee of the government engaged in any phase of the information program, radio, press, or films?

Mr. Fast. That is a very vague question, and I can’t possibly answer it certainly. It does not seem to my recollection that I have had, but I might have met, on this occasion or that occasion, such a person.

Mr. Cahn. You do not know any individual today to be an employee engaged in radio, press, or film work for the United States government?

Mr. Fast. Offhand, I can not think of any.

The Chairman. Anything further? Thank you very much.

Counsel will be in touch with your attorney.

Mr. Cohn. The witness remains under subpoena.

[Whereupon, at 1:15 p.m., the hearing was adjourned.33

NOTES:

- Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), 18-19.

- Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website, Box 77, State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/_resources/images/psf/psfb000259.pdf. The Welles memorandum is also accessible at: State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, From Collection: FDR-FDRPSF Departmental Correspondence, Series: Departmental Correspondence, 1933 – 1945 Collection: President’s Secretary’s File (Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration), 1933 – 1945, National Archives Identifier: 16619284, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/16619284. Also see: Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director was a pro-Soviet Communist sympathizer, State Dept. warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 4, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/.

- Epstein, Julius. Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 81st Congress, Second Session, Appendix. Part 17 ed. Vol. 96. August 4, 1950, to September 22, 1950. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1950, A5744-A5745. See: Cold War Radio Museum, ‘Love for Stalin’ at wartime Voice of America, October 6, 2016, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/love-for-stalin-at-wartime-voice-of-america/

- Gerald Sorin, Howard Fast: Life and Literature in the Left Lane (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), 19.

- Amanda Bennett, Voice of America Director, “Trump’s ‘worldwide network’ is a great idea. But it already exists.” The Washington Post, November 27, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/trumps-worldwide-network-is-a-great-idea-but-it-already-exists/2018/11/27/79b320bc-f269-11e8-bc79-68604ed88993_story.html.

- A report of the Working Group on Chinese Influence Activities in the United States, the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and the Center on US-China Relations at Asia Society in New York, October 24, 2018, https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/chineseinfluence_americaninterests_fullreport_web.pdf.

- American Foreign Policy Council (AFPC), U.S. Persian Media Study, October 6, 2017, https://www.bbg.gov/wp-content/media/2011/11/AFPC_Persian-Language-Broadcasting-Study_synthesis-report.pdf.

- Nikolai Rudenskiy, Voice of America Russian Website Evaluation, 2011, http://bbgwatch.com/bbgwatch/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Rudenskiy.pdf.

- Gerald Sorin, Howard Fast: Life and Literature in the Left Lane (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), 330-333.