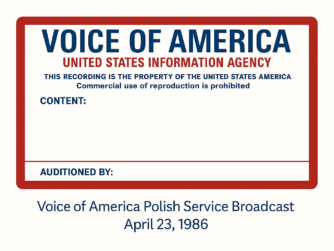

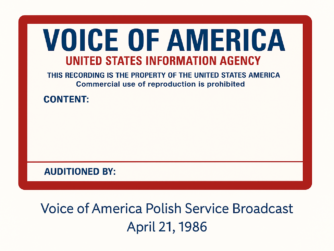

Recovering a forgotten Voice of America / RIAS relay preserved on magnetic tape

At a glance

- Listen first: Murrow’s introduction + RIAS Christmas segments (VOA WW English relay, Dec. 1961)

- Why it matters: A rare example of Cold War broadcasting as “human voice” diplomacy across a sealed border

- Deep dive: VOA’s institutional history, Murrow’s USIA role, and primary-source documents

Jump to a section

- I. Introduction – Why This Tape Matters

- II. Murrow’s Voice: A Bridge Across the Wall

- III. The Hidden Story – VOA’s Pro-Soviet Origins

- IV. Religion, Resistance, and What Washington Missed

- V. U.S. Broadcasting Strategy After 1945 – What Changed, What Didn’t

- VI. The Berlin Voices: Clips from the Broadcast

- VII. Murrow Inside Government – The Censorship Dilemma

- VIII. Artifact Description – Tape, Provenance, Label Notes

- IX. Full Primary Source Transcripts

I. Introduction – Why This Tape Matters

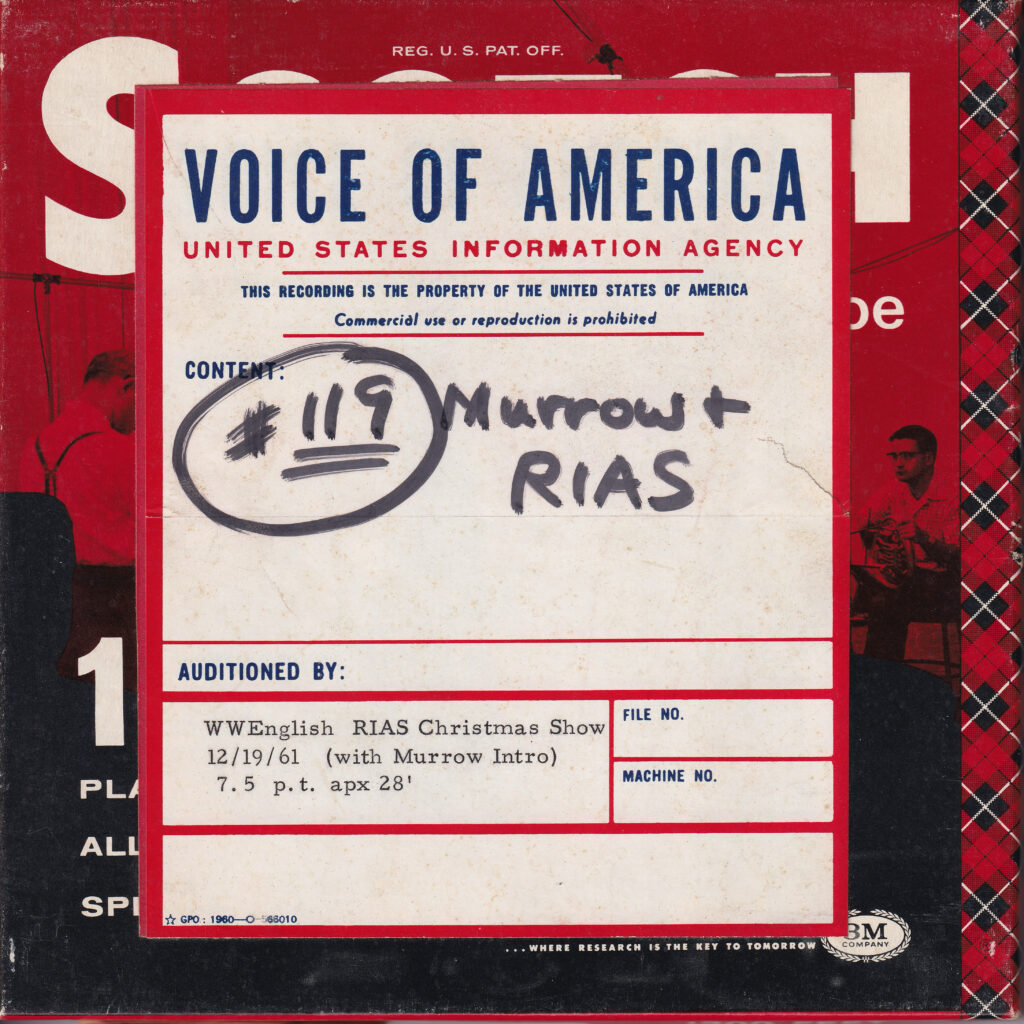

In December 1961 — just months after the Berlin Wall divided Berlin and reshaped Cold War realities — the Voice of America (VOA) presented a special World-Wide English broadcast featuring English-language renditions of Christmas material first heard on RIAS, the radio in the American sector of West Berlin. Introduced by United States Information Agency (USIA) Director Edward R. Murrow, the program reflected the Kennedy administration’s determination to strengthen U.S. outreach and counter communist propaganda and censorship with renewed clarity. Preserved today on its original reel-to-reel tape by the Cold War Radio Museum, this rare recording shows how Washington sought to reach across a sealed border not with polemics, but through voices of East German defectors, messages from families separated by the Wall, music, and a quiet affirmation of connection and the ideas of freedom.

RIAS stood for Radio in the American Sector; German: Rundfunk im amerikanischen Sektor, a radio founded by the U.S. occupational authorities in 1946 that evolved into a surrogate home service for East German listeners. RIAS remained under U.S. oversight through the U.S. High Commission and later USIA, though day-to-day production was German-run. In this Voice of America English-language broadcast about RIAS, a U.S. Senator speaks directly to East German listeners, promising that “Americans have not forgotten you,” and listeners hear family greetings that cannot longer cross the Wall. Together, these political and personal voices show why RIAS mattered in 1961 – and why this recording remains worth preserving today.

This recording is both a Christmas message and a Cold War document — evidence of how radio functioned as a form of human rights intervention when the Soviet Union and other communist-ruled nations closed physical borders. Edward Murrow’s broadcast was shaped by his instinct for decisive moral action, yet the historical picture is more complex. He believed that President Kennedy and the leaders of other Western powers could have stopped the Wall from going up. Others feared that any attempt by U.S. forces to interfere with the initial construction of the Berlin Wall could have triggered unpredictable escalation — possibly even armed confrontation between American and Soviet units. Friends who heard Murrow’s lament later suggested that his frustration, while emotionally compelling, did not fully account for the risks of counteraction in August 1961.1 We will never know whether intervention would have halted the Wall or merely produced a tragic bloodbath. What remains certain is that Murrow interpreted the moment as an example of hesitation and lack of leadership in the West.

After President Kennedy appointed him USIA director — and with the President’s explicit backing — Murrow moved quickly to strengthen U.S. efforts to counter communist propaganda not only in East Germany but throughout the Soviet Bloc and in countries facing the threat of communist expansion. In government, he did not seek to reshape the Voice of America in CBS’s image; instead, he insisted that a taxpayer-funded international broadcaster must speak with a different clarity and edge — reflecting national purpose, congressional intent, and the expectations of Americans whose dollars financed it. The 1961 Christmas program reflects that shift: a broadcast that used culture, memory, and the human voice as instruments of policy, reaching across borders where physical movement and open communication had been denied.

Rather than answer the Wall with force — a response that risked bloodshed and a wider East–West confrontation — Kennedy chose to fight with ideas and information. Under his administration, U.S.-funded radio broadcasts became a central instrument of policy: feared by the Kremlin and its satellite regimes, yet sought after by the very populations those regimes tried to seal off. Whether Kennedy or Murrow fully foresaw that weakening a totalitarian system through words would take decades, the record shows that this strategy became a defining pillar of Western policy. But it was never a substitute for hard power. The credibility and reach of this informational offensive rested on the parallel existence of NATO, U.S. military strength, and the political will to defend the West if necessary. Nowhere is this clearer than in the contrasting outcomes of the Cold War in Europe and the failure to contain communism in Southeast Asia with military force. Containment and deterrence proved effective in combination with information and public diplomacy outreach but not everywhere. It did not work in Viertnam, where the United States became militarily involved in a post-colonial nation. Later, President Reagan would expand both sides of the equation — dramatically growing U.S. defense spending but without a major military engagement abroad while also investing more in surrogate broadcasting, public diplomacy, and information warfare. The long arc of history shows that words alone could not have accomplished the peaceful collapse of Soviet rule, but when fused with deterrence and the ability to back principle with force, they proved more powerful in the end than tanks or troops. These broadcasts succeeded without triggering a violent conflict.

Archival Note — Early RIAS: “The Voice of America in Berlin” (1949)

(Photograph on file; not reproduced here)

The Cold War Radio Museum holds a 1949 photograph depicting American and German officials associated with RIAS – Radio in the American Sector (Berlin). Out of an abundance of caution regarding image-copyright status and reproduction rights, the photograph is not published online here. Scholars and credentialed researchers may request access to view the original image by contacting the Museum.

Although not displayed, the photograph is historically significant because the reverse caption refers to RIAS as “the Voice of America in Berlin” and identifies senior figures as “American and German officials of radio RIAS.” This wording reflects the institutional reality of the late 1940s: RIAS was funded and strategically supervised by the U.S. Government, including a U.S. Control Officer and an American Director, while German editors and announcers delivered most on-air content. The American-German partnership was framed as joint, but the early governance structure remained largely American.

This hybrid identity mattered. It enabled RIAS to evolve — over the 1950s — from being dominated by U.S. oversight into a true German surrogate broadcaster, speaking to East Germans in their own language, idiom, cultural references, and emotional register. By contrast, the Voice of America remained structurally and editorially American, broadcasting from America to the world, usually in English. There were many small VOA foreign language services, but with the funds and resources given to them by the management, they could do little more than translate programs prepared in English.

Context: RIAS, VOA, and Rare Moments of Institutional Cooperation

The Edward R. Murrow / VOA / RIAS tape featured in this article — a 1961 VOA World-Wide English program introducing RIAS to international audiences — is a valuable example of cross-institutional cooperation among U.S. public diplomacy actors:

- American USIA officials (Washington-based public diplomacy)

- VOA officials and English-language editors (global news)

- RIAS German broadcasters (local surrogate voice for East Germany under American management)

Such joint projects were not common. RIAS, much like its later counterparts Radio Free Europe (RFE) and Radio Liberty (RL), guarded its identity as a surrogate broadcaster and generally avoided being seen as part of U.S. government information-policy messaging, especially in English. Their legitimacy rested on sounding local — Polish voices for Poland, Czech and Slovak voices for Czechoslovakia, German voices for East Berlin — not voices speaking about them from Washington.

Therefore, the Murrow-introduced 1961 program was not meant for East German listeners; it was aimed at VOA’s English-speaking global audience, functioning largely as a public relations effort explaining RIAS to the world, rather than as a routine program of coordinated messaging.

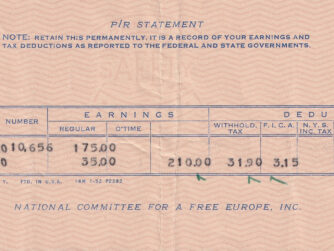

The surviving tape, labeled ‘WW English – RIAS Christmas Show – 12/19/61 (with Murrow intro),’ is held in the Cold War Radio Museum archive.

II. Murrow’s Voice: A Bridge Across the Wall

🎧 LISTEN FIRST

Edward R. Murrow introduces a RIAS Christmas broadcast from Berlin (December 1961).

Clip 1 — Murrow/VOA Introduction

Murrow’s broadcast about the Berlin Wall carries historical ironies that were largely forgotten at the time and remain insufficiently understood even today — more than sixty years later, at a moment when Russia’s propaganda and influence are again resurgent in the United States and in global affairs. Like President Kennedy, who appointed him USIA director, Murrow believed that U.S. information policy should help undermine Soviet domination in Eastern and Central Europe and counter communist advances in Cuba.

Yet less than two decades earlier, the very U.S. government radio outlet Murrow now symbolically represented — the Voice of America — had played a dramatically different role. During World War II, VOA functioned as an anti-German and anti-Japanese propaganda radio operation, but it was influenced by pro-Soviet officials within the Roosevelt administration and communist sympathizers among its journalists. At times, its early programming supported narratives that even exceeded President Roosevelt’s own willingness to appease Stalin. Roosevelt, though determined to maintain wartime unity with the Soviet Union, was sensitive to the political optics of government-funded domestic propaganda as unacceptable to most Americans and aware of the need to retain the Polish-American vote in the 1944 election — while concealing from the voters negotiations that would ultimately concede Poland’s freedom and territorial integrity to Soviet control. He deceived Polish-American leaders about his deals with Stalin at Poland’s expense to gain their support. Arthur Bliss Lane, who as the U.S. Ambassador in Warsaw from 1945 to 1947, documented the Soviet and communist takeover of the country, observed in his book I Saw Poland Betrayed Roosevelt’s manipulation of the Polish American public opinion. 2 As Ambassador Bliss Lane wrote after he had resigned from the State Department in protest against the appeasement of Stalin, President Roosevelt “had already agreed at Tehran to the sacrifice of a great area east of the Curzon Line to the Soviet Union.” Charles Rozmarek, President of the PAC, said later that had the Yalta Conference been held before the presidential elections of 1944, Mr. Roosevelt would not have been reelected, because of the votes of Americans linked by blood to those nations which had been “sold down the river.”3

General Dwight D. Eisenhower viewed some of VOA’s wartime broadcasts as a military liability. According to Eisenhower, communist-inspired excesses by early VOA broadcasters risked endangering American soldiers when VOA ridiculed tactical agreements he had reached with certain Vichy French and Italian officials to persuade them to abandon cooperation with Nazi Germany. In his memoir, Eisenhower recalled that President Roosevelt intervened to stop what he considered VOA’s “insubordination.” He also complained that as president, a VOA reporter attempted to obtain a statement from a member of Congress to attack his Middle East policy for domestic partisan purposes—a request the lawmaker reportedly refused.4

Poor personnel security, Soviet influence over elements of wartime propaganda, and the use of VOA broadcasts for domestic political purposes contributed to President Truman’s decision to abolish the Office of War Information in 1945. VOA was transferred to the State Department, and Truman administration appointees dismissed pro-Soviet staff while establishing a hiring policy that gave preference to American citizens. The Smith–Mundt Act, signed by President Truman in 1948, mandated stricter security vetting of personnel and also prohibited domestic dissemination of VOA programs — a restriction that remained in place until being loosened in 2012.

Murrow’s introduction to the RIAS program segments carries historical ironies that were largely forgotten at the time and remain insufficiently understood even today. Like President Kennedy, who appointed him USIA director, Murrow believed that U.S. information policy should help undermine Soviet domination in Eastern and Central Europe and counter communist advances in Cuba. In contrast, during World War II, the Voice of America was at times much more pro-Soviet than even President Roosevelt was willing to tolerate, despite his desire to appease Stalin. While Roosevelt was more worried about domestic political scandals over some of VOA’s pro-communist programs and broadcasters and wanted to secure the Polish-American vote in the 1944 presidential elections by deceiving Polish-American leaders about his deal with Stalin at the expense of Poland’s territory and independence, General Eisenhower was worried about VOA propaganda putting the lives of American soldiers at risk.5

Among its early critics — including members of Congress from both parties — the Voice of America became associated with Roosevelt-era information policies that, at times, echoed Soviet narratives and helped reduce public resistance to Stalin’s designs on East-Central Europe. Its reputation was later further complicated by the continued postwar presence of officials sympathetic to pro-Soviet positions within segments of the U.S. government. By 1961, however, VOA had undergone a gradual but substantial transformation, beginning under President Truman and continuing through the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations. VOA’s impact was strongest in Eastern and Central Europe, where it attracted its largest audience. Although listeners there often desired more in-depth and locally focused coverage than VOA could provide, the service nevertheless became a powerful symbol of American solidarity and moral support. The task of reporting local news and offering commentary on domestic developments — along with the more defined mission of attempting to roll back communism and hasten national liberation — fell instead to Radio Free Europe and, later, Radio Liberty. By the early 1960s, VOA had emerged as a markedly different institution from the wartime service that once reflected Moscow’s line — becoming instead a non-military instrument of U.S. foreign policy that sought to halt the spread of communism by exposing its realities, abuses, and failures to global audiences.

↑ Back to top · ▶ Back to Murrow audio

III. The Hidden Story – VOA’s Pro-Soviet Origins

VOA During World War II: Closer to Moscow than Washington

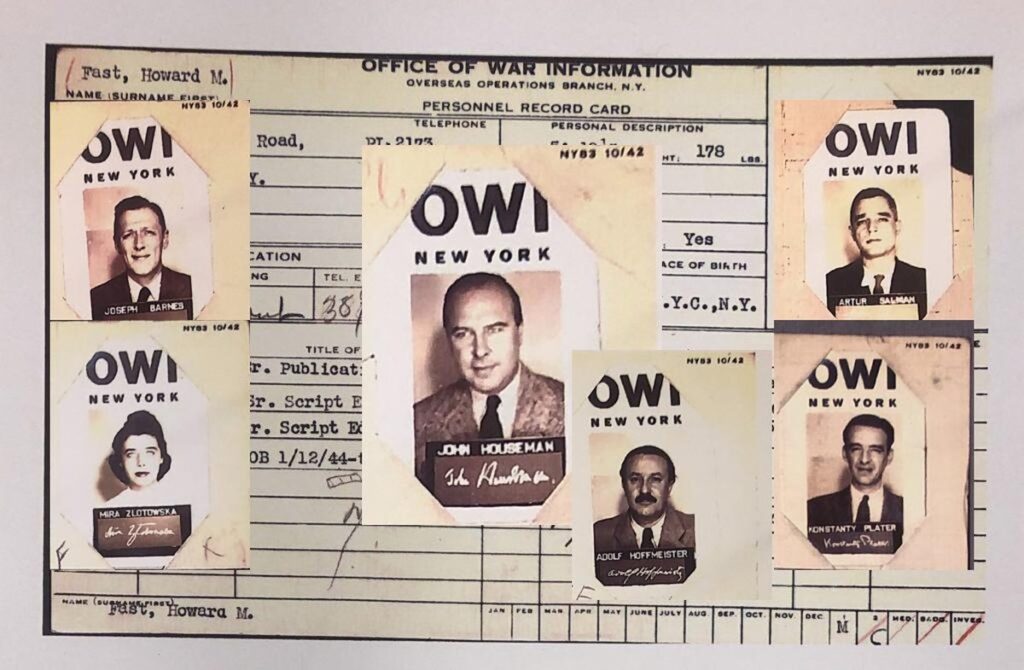

During World War II, the Voice of America helped to advance Stalin’s postwar objectives and contributed to the Soviet consolidation of power in Poland and other nations of East-Central Europe. VOA was then managed by U.S. government officials and journalists — among them Elmer Davis, a former CBS colleague whom Murrow later knew well — who, to varying degrees, adopted or tolerated narratives aligned with Moscow. Julius Epstein — a Jewish refugee journalist from Austria, a distant relative of composer Johann Strauss II, briefly a member of the German Communist Party before breaking with it, and a highly regarded contributor to European newspapers and magazines — arrived at the Voice of America in 1942 as a German Desk editor and later became the first former OWI employee to publicly expose VOA’s suppression of Soviet responsibility for the Katyn massacre; he described what he encountered as a newcomer in 1942:

I was immediately struck by the fact that the German desk was almost completely seized by extreme left-wingers who indulged in a purely and exaggerated pro-Stalinist propaganda.6

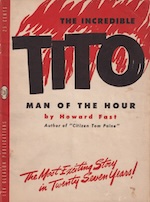

Officials in charge of OWI and VOA created an environment that enabled the hiring of Roosevelt loyalists as well as individuals sympathetic to Soviet-style communism. Howard Fast, the first chief writer and editor of VOA English news, censored reporting about Soviet atrocities and produced content that glorified Stalin and Tito.7

Arthur Krock, Washington bureau chief of The New York Times, wrote that OWI spoke with an ideology “that conforms much more closely to the Moscow than to the Washington-London line.” He added: “

Those administrators of the foreign propaganda division who are not confused, or deliberate undercutters of the State Department, are incompetent.8

Some of VOA’s Communists and Soviet sympathizers ended up working for pro-Soviet regimes after the war as anti-American propagandists and defenders of the Soviet Katyn lie (Stefan Arski, aka Artur Salman, in Poland), media advisors (Mira Złotowska, later Michałowska, in Poland) or diplomats (Adolf Hoffmeister, in Czechoslovakia).

Murrow’s message to East Germans in 1961 thus symbolized a definitive break with VOA’s pro-Soviet origins. Its uncomfortable early history — still unknown to most Americans — was understandably absent from his narrative. The RIAS Christmas broadcast preserved in this museum is, therefore, not only an audio relic; it marks a pivot point between VOA’s compromised wartime beginnings and its later role as a voice of democratic resistance.

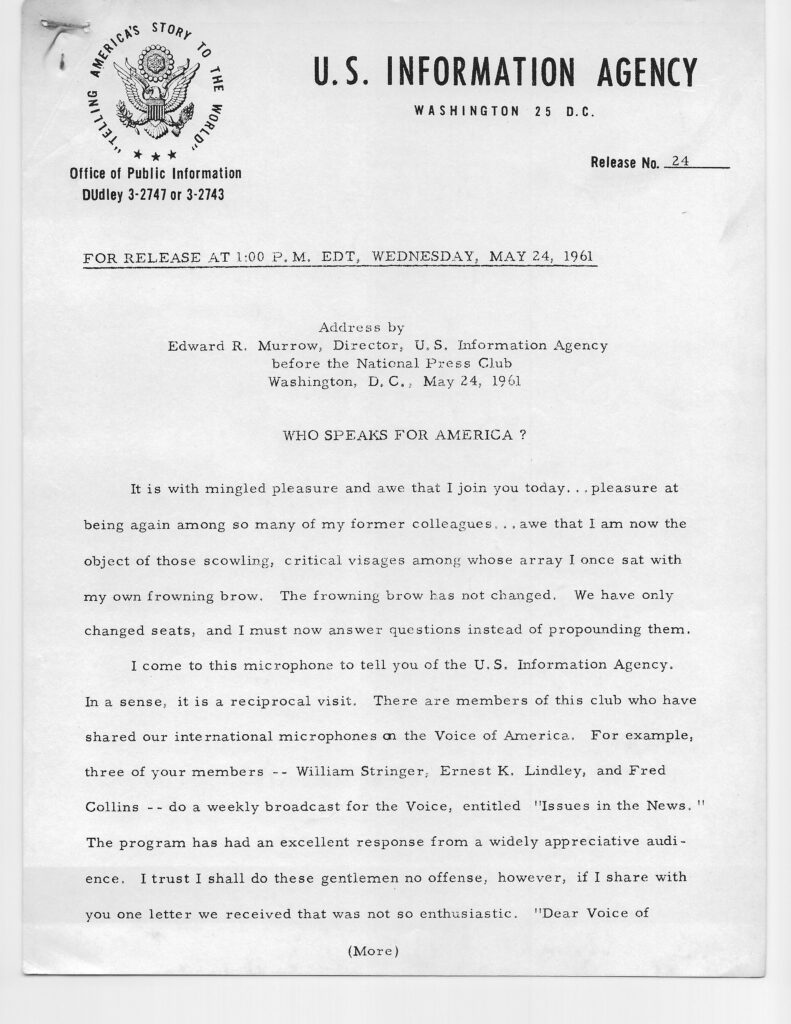

Murrow as Broadcaster and Official: From Truth to “Persuasion”

Edward R. Murrow believed deeply in truthful reporting. He possessed a keen understanding of history, foreign policy, and foreign cultures. Yet within the Cold War framework of his time, he also accepted that U.S.-funded broadcasting would, by necessity, counter hostile propaganda — not only with facts but also with values and interpretation. In a confidential memorandum at USIA, Murrow wrote:

Decisions by the President call for an energetic campaign of persuasion — by diplomacy and propaganda — to unify Latin America against Castro, to isolate and ‘quarantine him,’ to nullify his potential for subversion, and ultimately so to weaken him in Cuba and in the rest of Latin America that his Cuban opponents (and Hemisphere pressures) can overthrow him.9

In hoping that VOA broadcasts would help bring about regime change Murrow speaks here not as a CBS journalist but as a U.S. government official — his tone, content, and omissions reflect the bureaucratic world he now inhabited. Murrow’s Press Club speech the same year reveals what he believed public diplomacy and hard-hitting U.S. government-funded journalism abroad should accomplish — and provides a lens for understanding the language in the RIAS Christmas program.

To understand why Murrow’s reassurance mattered in 1961, one must recall what the Voice of America once was — and how different it had been during World War II.

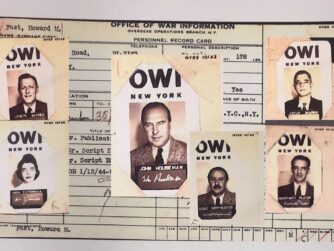

OWI, Early VOA, and the Pro-Soviet Line

In the 1940s, during the Roosevelt administration and World War II, the Voice of America was shaped by Soviet-aligned policy and personnel within the Office of War Information (OWI). Under strongly pro-Soviet OWI officials, some VOA staff were later identified by congressional investigators as Communist Party members or sympathizers who supported the creation of communist, often anti-religious regimes in Eastern Europe. Among them was VOA’s first director, John Houseman, who — according to later congressional investigations — hired several individuals associated with the Communist Party for key VOA positions, and Howard Fast, the future recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize (1953). It was President Harry Truman who began reforming VOA and narrowing Soviet influence in the late 1940s, a process that was continued under the Eisenhower administration.

Murrow himself had nothing to do with the creation of VOA and, as USIA director, had only limited direct impact on VOA’s day-to-day programming in the 1960s. He was, however, a strong believer in truthful journalism and possessed an extraordinary talent as a reporter and communicator.

The Myth That Murrow “Helped Create” VOA

Edward R. Murrow did not “help to create VOA,” as is sometimes claimed.10 He had no involvement in the Voice of America during its early years. As Murrow’s biographer Ann M. Sperber documents in Murrow: His Life and Times, Robert E. Sherwood — President Roosevelt’s speechwriter, personal friend, and one of the two top officials in the Office of War Information (responsible for overseas VOA broadcasts) — wanted Murrow to be in charge of the international radio side of OWI, a job later divided between Joseph Barnes and John Houseman. Murrow declined the offer.11

Having been rebuffed by Murrow, Robert E. Sherwood appealed in January 1942 to President Roosevelt’s closest adviser and informal liaison to Soviet leaders, Harry Hopkins. Sherwood informed Hopkins that there existed a large audience for English-language broadcasts to Europe—a claim that was largely inaccurate outside Great Britain, though he correctly noted that the BBC already dominated that particular audience.

While emphasizing that the new government broadcasting operation would produce programs in many languages, Sherwood wrote that for the English-language broadcasts—what he called “the voice of America”—he was “most anxious to get” Edward R. Murrow.12 Murrow, however, wished to return to London to continue his CBS reporting. Aware that the government position would involve a substantial cut in salary, Sherwood suggested that a personal intervention by President Roosevelt might persuade the broadcaster to accept. Hopkins complied, sending Murrow a telegram from the White House urging him to take the post. More than a week later, Murrow replied tersely: “AFTER MUCH SOUL SEARCHING AM CONVINCED MY DUTY IS TO GO BACK TO LONDON.”13

In later decades—after serious controversies surrounding the early leadership of the Office of War Information and the wartime Voice of America—VOA would come to rely on Murrow as a symbolic anchor whose reputation could retroactively confer legitimacy on U.S. government broadcasting. This occurred despite the fact that Murrow played no operational role in VOA during World War II. The only indirect connection sometimes cited is his participation, years later, in the Radio Advisory Committee, convened at the invitation of William Benton—publisher of the Encyclopædia Britannica, former U.S. senator from Connecticut, and Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs from 1945 to 1947.

The committee, composed of eight prominent publishers, educators, and broadcast executives, submitted its report to the State Department in May 1947. It urged expansion of the Department’s international shortwave service—explicitly referring to it as the “Voice of America”—alongside broader cultural relations programs, warning that failure to do so could result in a “serious setback” to U.S. relations with the rest of the world.14

At the same time, the report stressed that international information efforts should, wherever possible, be conducted through private agencies, “since this is in the American tradition.”15

The committee concluded that only when private U.S. media were unable to disseminate information abroad — because of financial constraints or censorship — should the U.S. government intervene directly to ensure that the Voice of America could be heard. Murrow and other committee members therefore recommended the creation of a public corporation, authorized by Congress and funded through appropriations but operating under the supervision of an independent board of trustees rather than a government department.16 This recommendation, endorsed by Murrow, was not adopted for VOA, which remained under State Department control. It was, however, later implemented in the organizational design of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.

The institutional foundations of VOA itself were laid instead by Robert E. Sherwood, head of OWI’s Overseas Branch, and his deputy Joseph Barnes, with assistance from John Houseman, later celebrated as VOA’s “first director.” Houseman was not a journalist by training but a propagandist, best known as co-producer of the famous radio drama often cited as an early example of mass-media–induced panic.17 During the war, he recruited Communist Party members and individuals sympathetic to the Soviet Union into OWI broadcasting roles, and in 1943 the Roosevelt administration declined to issue him a passport for official government travel—an extraordinary step that reflected growing concern about his political judgment and associations.

Archival correspondence shows that Houseman’s VOA employment ended after the State Department, with approval from U.S. military authorities, declined to issue him a passport. This information did not become public, and VOA leaders continued to present him as a champion of truthful journalism.18

Even decades later, Murrow’s photograph hung in VOA’s newsroom. Murrow is often quoted as saying: “To be persuasive we must be believable; to be believable we must be credible; to be credible we must be truthful.” His tenure at USIA, however, showed the complexities and constraints of applying that ideal within government. As USIA director, he ordered the cancellation of a VOA program on the presence of American nuclear weapons on Canadian soil at a moment when the Kennedy administration sought to quiet political controversy; he reversed this decision only after outside journalist Bill Stringer — the Christian Science Monitor bureau chief and moderator of the program — threatened to withdraw his participation.19 In a separate incident, after VOA director Henry Loomis and two VOA writers presented him with a program on Soviet nuclear testing that Murrow found insufficiently forceful, he instructed them to “really hit them,” and approved the broadcast only after the insertion of explosion sound effects and warnings of mass casualties.20

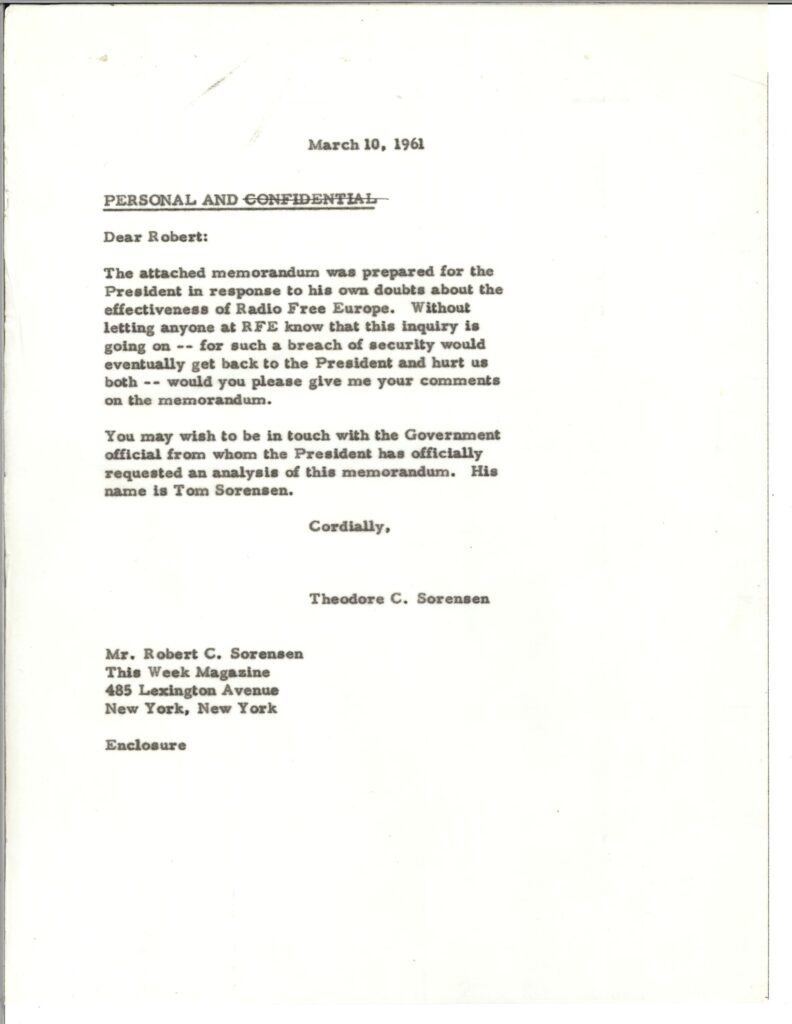

Murrow’s capacity to intervene in programming was strengthened by internal political networks. His principal USIA deputy, Thomas C. Sorensen, was the younger brother of Theodore C. “Ted” Sorensen, President Kennedy’s closest adviser and chief speechwriter, who helped shape the administration’s foreign-policy messaging at its highest level. In the assessment of Shawn J. Parry-Giles, a scholar of U.S. public diplomacy and the history of the United States Information Agency, Edward R. Murrow embraced what she characterizes as a “militarized propaganda program,”explicitly resisting Dwight D. Eisenhower’s efforts to recast USIA as a more ostensibly “objective” news organization.21

Rather than adopting Eisenhower’s restrained model, Parry-Giles argues that Murrow aligned himself with the more assertive information strategies developed during the Campaign of Truth under the Harry S. Truman administration — strategies explicitly designed to confront Soviet propaganda and limit communist political influence abroad.22

Claude Groce stated that during Murrow’s tenure at USIA, he received — in his words — “the only time in my entire memory of my days with the Voice of America” a written instruction on how to play the news, sent under Tom Sorensen’s authority: “accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative, don’t mess with Mr. In-between.”23 Murrow’s other deputy, Don Wilson, was, Groce recalled, a personal friend of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy.24 Together, the two deputies symbolized what may be described as ideological and political nepotism within U.S. international broadcasting — not invented by Murrow, but inherited by him, and traceable to earlier wartime precedents.

Indeed, this pattern long predated the Kennedy administration. The first wartime head of the Voice of America, playwright Robert E. Sherwood, was also President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s speechwriter and political confidant. Sherwood issued weekly written propaganda directives guiding VOA content and, in one notorious case, explicitly instructed VOA to promote the Soviet version of the Katyn massacre and suppress contrary evidence.25

Roosevelt later assigned Sherwood to coordinate U.S.–Soviet propaganda from wartime London — illustrating that White House–directed editorial control was built into VOA’s institutional DNA from the start.26

Claude Groce’s recollections therefore cannot be read as literal transcripts of policy, but as revealing testimony about how VOA staff experienced control. He claimed Murrow may have been “sandbagged” by his politically connected deputies, yet simultaneously described Murrow approving harsh edits, overruling programs, and allowing USIA policy officials into the newsroom during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when Burnett Anderson was placed “in a censor role.”27 Groce also recounted that senior VOA editor John Albert drafted a memo comparing USIA censorship during the crisis to Goebbels’s operation; he confirmed he read this memo, though he did not retain a copy, leaving interpretation to memory.28

Yet one dimension is almost entirely absent from VOA’s later institutional memory: why Murrow and USIA believed oversight was necessary. VOA’s wartime news staff — influenced by the Popular Front atmosphere of the early 1940s — at times broadcast pro-Soviet messaging, suppressed information about Stalinist crimes, and, according to Dwight D. Eisenhower, endangered American soldiers through broadcasts he deemed reckless. The agency’s leadership in later decades never fully confronted this history. Instead, it was obscured from Americans, forgotten internally, and never systematically taught to succeeding generations of VOA journalists. This burial of institutional memory — combined with the postwar professionalization of an English-language newsroom staffed largely by journalists who had never lived under communism — meant that later VOA employees did not understand the magnitude of the threat of foreign influence, did not see the need for oversight, and came to believe that VOA’s credibility depended on operating without any policy constraint.

In this vacuum of historical understanding, a mythic Murrow emerged — a selective memory emphasizing Murrow as a paragon of journalistic independence while omitting the Murrow who wielded information deliberately as a Cold War weapon. That myth would later shape VOA editorial decisions decades after his death and serve as a rhetorical tool for resisting even minimal oversight.

Some VOA English-language journalists invoked this later, mythologized Murrow to argue that he would have objected to countering violent extremism with explicit language — such as calling Hamas “terrorists” rather than “fighters” — because such language could harm VOA’s credibility. In their view, as a believer in freedom of the press, he would not have objected to VOA posting a graphic mourning Fidel Castro’s death or VOA praising Lenin Prize winner Angela Davis as a fighter for women’s rights.29

In contrast, Murrow’s RIAS broadcast, his National Press Club speech, and his classified USIA memoranda demonstrate his full willingness to wage information war against enemies of democracy — be they in Moscow, East Berlin, Cuba, or elsewhere.30

VOA – Castro 2016

USIA – Castro 1961

Question: Returning to the Cuban situation, please assess the propaganda effects of the “tractors for prisoners” affair.

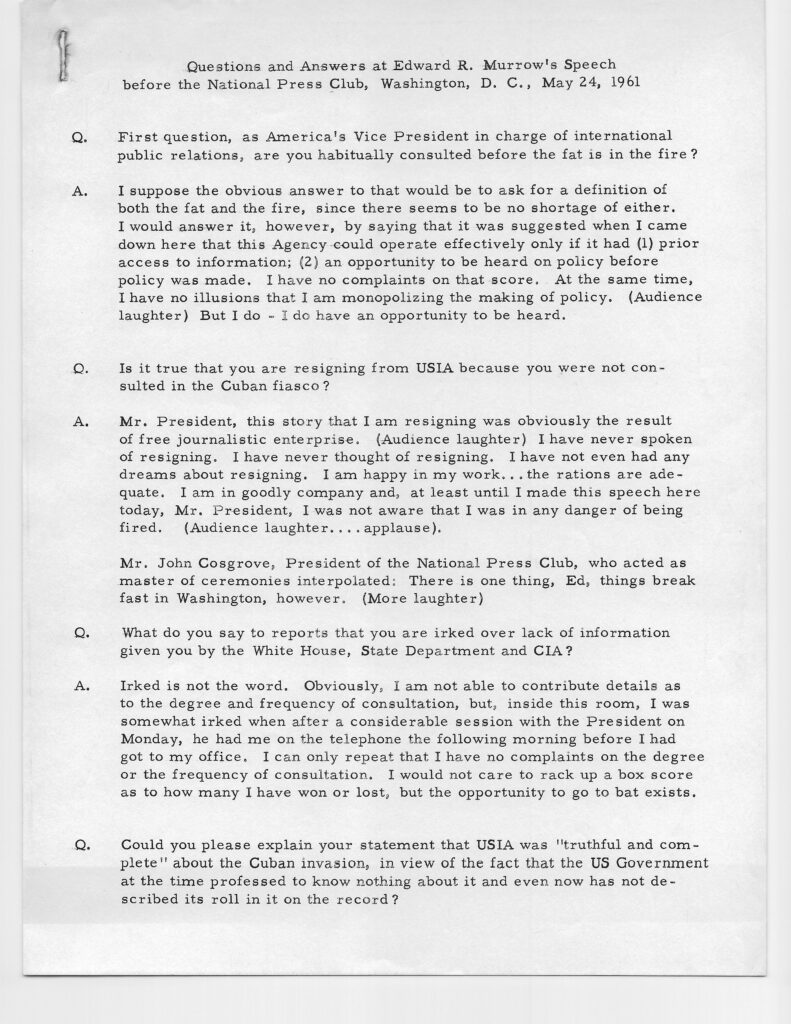

Questions and Answers at Edward R. Murrow’s Speech before the National Press Club, Washington, D.C., May 24, 1961

Murrow: … As Senator Smathers said I believe yesterday, Castro’s offer to exchange prisoners for tractors was a monumental propaganda blunder. The world-wide reaction was almost universally hostile. The obvious parallel was drawn all around the world between Castro’s offer and the one made by Hitler when he offered to trade Jews for trucks. … What he did initially, of course, was to demonstrate again to the world in dramatic fashion that the Communist machine operates without regard for those human values and human beings that are the hallmark of civilized society. And it seems to me that had American citizens remained mute and refused to act, they would, one have denied their heritage and cause much of the world to believe we value our dollars and machines above the freedom of men who are willing to risk their lives in an effort to regain freedom for their fellow countrymen.

Could Murrow Have Acted Differently During WWII?

One cannot know how Murrow would have behaved had he taken a wartime government post. But it seems unlikely that he would have echoed Soviet disinformation in the manner of OWI director Elmer Davis or certain early VOA figures — such as Wallace Carroll, the future news editor of the Washington bureau of The New York Times, who even in 1948 defended Stalin’s Katyn-massacre lie in Persuade or Perish. 31 It is unlikely that Murrow would have chosen John Houseman or Howard Fast for any positions within the Voice of America.

The unwillingness to call communist atrocity by its name was a hallmark of OWI–VOA wartime output. Truthful reporting about Katyn or the Gulag might have risked damaging the alliance with Stalin. Still, VOA’s coverup of Katyn continued after the war, when the alliance rationale no longer applied. The earlier concealment made it easier for President Roosevelt to grant concessions that placed Eastern and Central Europe under Soviet domination for decades. Whether Murrow would have participated in such a coverup can never be known.

What is known is that under OWI leaders such as Owen Lattimore, Joseph Barnes, Wallace Carroll, John Houseman, Robert E. Sherwood, and Elmer Davis, VOA repeatedly misled foreign and domestic audiences about Soviet Russia and the communists in China. Professor Owen Lattimore, head of VOA broadcasts to Asia, accompanied Vice President Henry A. Wallace on his 1944 visit to Russia and later published in National Geographic a glowing description of the Kolyma gold mines — one of Stalin’s deadliest Gulag sites — claiming prisoners were “volunteer workers” for whom “extensive greenhouses growing tomatoes, cucumbers, and even melons” were built “to make sure that the hardy miners got enough vitamins!” [Exclamation in the original article.]32

Katyn, Domestic Propaganda, and Murrow’s Different Stance

Even though members of Congress — alarmed about the executive branch using government funds to propagandize to Americans — eliminated in 1943 almost all of the OWI’s domestic propaganda budget in a bipartisan vote, some of these fellow-traveler journalists continued to promote highly deceptive views of Stalin and communism in the United States using their access to U.S. radio networks, newspapers, and magazines. Edward R. Murrow was not one of them. Toward the end of the war, he became increasingly alarmed about Stalin’s intentions and secret U.S. concessions to Russia at the expense of Poland and other countries in East-Central Europe. In an exchange of letters with OWI director and former CBS colleague Elmer Davis, Murrow rejected Davis’s criticism that he was too negative in reporting on Soviet actions. Davis urged him to be patient and hope for the best. Murrow responded that saving Eastern Europe from Russian domination would require more than a single miracle.33

While Houseman and Fast viewed the Polish Government-in-Exile in London with unmasked contempt, and Elmer Davis spoke dismissively to members of Congress about the wartime Polish ambassador to Washington, Jan Ciechanowski, who repeatedly warned him and State Department diplomats about VOA’s use of Soviet propaganda, Murrow maintained contacts with Polish and other Eastern European exiles in Britain and used their information about Russia. He pointed out in his response to Senator McCarthy in 1954 that he had friends in Eastern Europe who were murdered or fled into exile.34

From See It Now: “Edward R. Murrow – Response to Senator Joseph McCarthy,” CBS Television, April 13, 1954.

I require no lectures from the junior Senator from Wisconsin as to the dangers or terrors of Communism. Having watched the aggressive forces at work in Western Europe, having had friends in Eastern Europe butchered and driven into exile, having broadcast from London in 1943 that the Russians were responsible for the Katyn massacre, having told the story of the Russian refusal to allow allied aircraft to land on Russian fields after dropping supplies to those who rose in Warsaw — and then were betrayed by the Russians — and having been denounced by the Russian radio for these reports, I cannot feel that I require instruction from the Senator on the evils of Communism.35

Soviet propaganda organs such as TASS routinely attacked such Western coverage as “anti-Soviet” and hostile to socialist achievements, though direct Soviet press statements naming Murrow by name are not readily documented in the archival record. In contrast to Murrow’s assertions about his reporting on Soviet-Polish issues, the Office of War Information — and therefore the wartime Voice of America — aligned their broadcasts with the Soviet narrative on Katyn, actively disseminating Moscow’s version of events and suppressing competing evidence to the contrary.36

Sometime in April 1943, OWI director Elmer Davis wrote a special radio commentary in which he blamed the Katyn massacre on the Nazis. It was broadcast abroad by VOA and domestically on American radio networks. At the time, even the State Department advised the OWI to avoid reporting on the Katyn story altogether “if at all possible” because the evidence was inconclusive.37

Davis later claimed before Congress that he was convinced the Germans were responsible for the murders.38 He, however, almost certainly had access to information that strongly pointed to the Soviet responsibility for the crime. As a journalist, he could have easily asked questions of the right sources, including State Department officials, Ambassador Jan Ciechanowski representing the Polish Government-in-Exile, and some American reporters who covered the Soviet Union from Washington, New York, or Chicago. “Mr. Davis, therefore, bears the responsibility for accepting the Soviet propaganda version of the Katyn massacre without full investigation,” the bipartisan Select Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives, which investigated the Katyn Massacre, concluded in its final report in 1952.

The governments-in-exile of German-occupied countries, some like Poland with considerable armed forces which were part of the anti-Nazi alliance, would be later betrayed by Roosevelt’s concessions to Stalin, made without their knowledge or approval. Still, FDR remained a hero for Murrow. He kept a bust of Franklin D. Roosevelt, a gift from Murrow’s reporter colleagues, in his USIA office.39 He had less admiration for John F. Kennedy, whom in private conversations he referred to as “that boy.”40 Initially, JFK wanted to recruit Frank Stanton, Murrow’s boss at CBS, for the USIA job, but Stanton recommended Murrow instead.41

From Wartime Propaganda to Moral Counter-Weight

While Murrow was broadcasting truthful news for CBS from London, VOA’s wartime output was being shaped by Davis, Sherwood, and other pro-Soviet officials in the Office of War Information. Voice of America programmers echoed Soviet propaganda lines, following the pattern set in the 1930s by The New York Times correspondent Walter Duranty. Duranty’s friend and fellow traveler, American journalist Joseph F. Barnes, held a senior role guiding VOA programming as John Houseman’s superior. Duranty’s misleading reporting helped shield Stalin and the Soviet Union from criticism, and VOA did something similar during the war.42 Its broadcasters repeated the Kremlin’s lie about the Katyn massacre, while Murrow is widely reported to have told his audience that the Soviets were responsible. He also reportedly covered Stalin’s betrayal of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising truthfully, at the same time as VOA, in line with Soviet preferences, largely marginalized non-communist Poles and their underground Home Army fighting the Germans.

In defending himself from false accusations by Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisconsin), Edward R. Murrow pointed out in a CBS’ See It Now television program broadcast on April 13, 1954, that he had gotten the Katyn story right when it was first reported by the Germans and correctly blamed the Soviets for the massacre of thousands of Polish POW military officers and intellectual leaders. The Cold War Radio Museum continues to search for Murrow’s recordings and scripts of wartime reports about Katyn and the Warsaw Uprising since they have not been made public in books or online.43 In Soviet and fellow-traveler propaganda, these anti-Nazi Poles were branded “fascists” and “reactionaries.” Former OWI and VOA Polish Desk editor Stefan Arski used such language in his anti-American propaganda following his return to Poland from the United States in 1947 and joining the Polish United Workers’ (communist) Party.44 In an anti-U.S. propaganda book published by the Warsaw regime in 1952, Arski attacked the Voice of America, his former U.S. government employer, and Polish anti-communist refugees, some of whom had replaced him and other Soviet sympathizers in VOA broadcasting jobs in the late 1940s and the early 1950s. He is particularly known for his vehement and consistent denials of Soviet responsibility for the Katyn massacre.

Against this backdrop, the 1961 RIAS Christmas broadcast takes on added meaning: it was not merely radio — it was a deliberate moral counter-weight to an earlier era of betrayal, coverup and silence in wartime VOA broadcasts.

↑ Back to top · ▶ Back to Murrow audio

IV. Religion, Resistance, and What Washington Missed

Listening to the VOA–RIAS program now, one also notices what was still not said. Even though the broadcast is centered on Christmas and on human rights violations in East Germany and other countries behind the Iron Curtain, there is almost no explicit mention of religious persecution and discrimination against Christians and other believers under communism. This absence does not necessarily imply intentional suppression; rather, it reflects USIA’s narrative priorities in 1961 and certain lack of understanding among USIA officials of the extent of persecution of religion by communist regimes (although not nearly as strong as when Stalin and Stalinist regimes ruled in the late 1940s and early 1950s) and the importance of religious faith and churches in sustaining resistance to communist rule.

Former American communist activist Bertram D. Wolfe, who renounced Soviet totalitarianism and during the Truman and Eisenhower administrations worked in the State Department producing Voice of America programs about the Soviet Katyn massacre, recalled that some American-born VOA journalists in the 1940s and early 1950s failed to grasp the nature of religious persecution and other human rights violations under communism:

“When I went to work for the Voice of America in the period from 1950 to 1954, religious leaders and believers were being framed, tortured, and sent to concentration camps in all the countries under Communist rule in Eastern Europe. After trying to get my script writers to write effective radio broadcasts to defend the religious freedom of the churchmen and devout believers who were being thus persecuted, I found that I had to write the scripts myself to get the requisite feeling into them. I did not believe what the persecuted believed, but I did believe in their right to freedom to harbor and practice their beliefs without interference.”45

USIA officials who, in 1961, may have drafted Murrow’s narration for the VOA–RIAS broadcast most likely did not fully appreciate that some of the strongest opposition to communism and Soviet domination came from deeply religious industrial workers and peasants, particularly in Poland. Murrow’s own May 1961 address at the National Press Club also contains no explicit reference to discrimination against religious believers or their central role in resisting communist oppression. His remarks focused instead on the global information struggle — Soviet and Cuban influence in the Western Hemisphere, new pressures in Southeast Asia, and the political awakening of Africa.

By contrast, many post-World War II VOA broadcasters who were refugees from communism believed that greater U.S. public diplomacy attention and resources should have been directed toward East-Central Europe and the Soviet Union, where audiences were both large and especially receptive to religious and moral arguments. In contrast to VOA, Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty devoted considerable airtime to religious programming and to exposing communist repression of religious institutions and individuals — an area largely neglected by VOA until the Reagan administration. Radio Free Europe also had more regular listeners behind the Iron Curtain than VOA.

Archival Note — Radio Free Europe, Munich (ca. December 1962)

In the Cold War Radio Museum collection, a Christmas-season photograph from Radio Free Europe’s Munich headquarters shows several children of RFE exile-journalist families gathered at a studio microphone bearing the RFE logo, singing seasonal hymns. The original caption reads: “RFE transmitters, broadcasting across the Iron Curtain, help to keep the Christmas spirit alive in communist lands.” (Cold War Radio Museum, private archive. Photograph reverse caption dated December 1960.) For copyright reasons, only a textual description is provided here. Researchers wishing to consult the photograph should contact the Cold War Radio Museum.

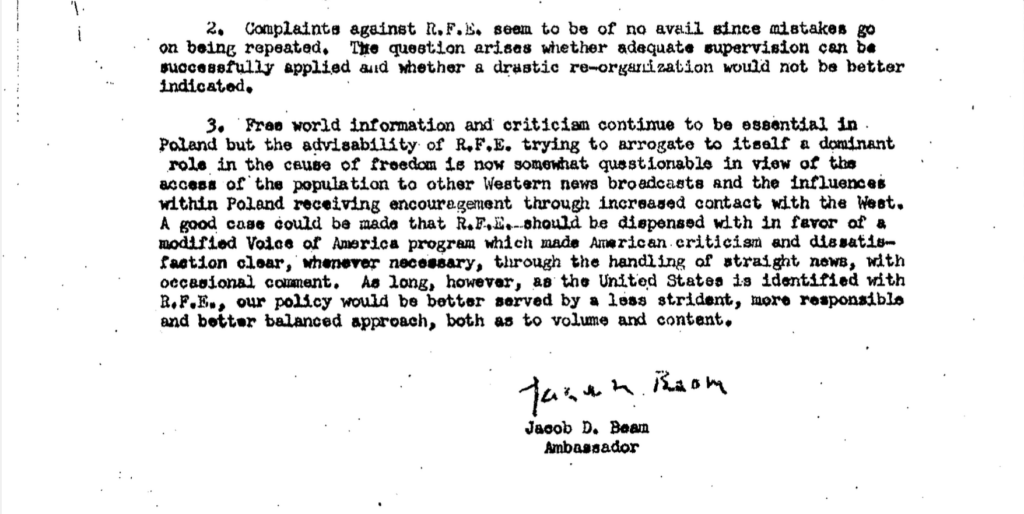

A Flawed Policy Blueprint for RFE: Internal White House Criticism of VOA and Radio Free Europe (1961)

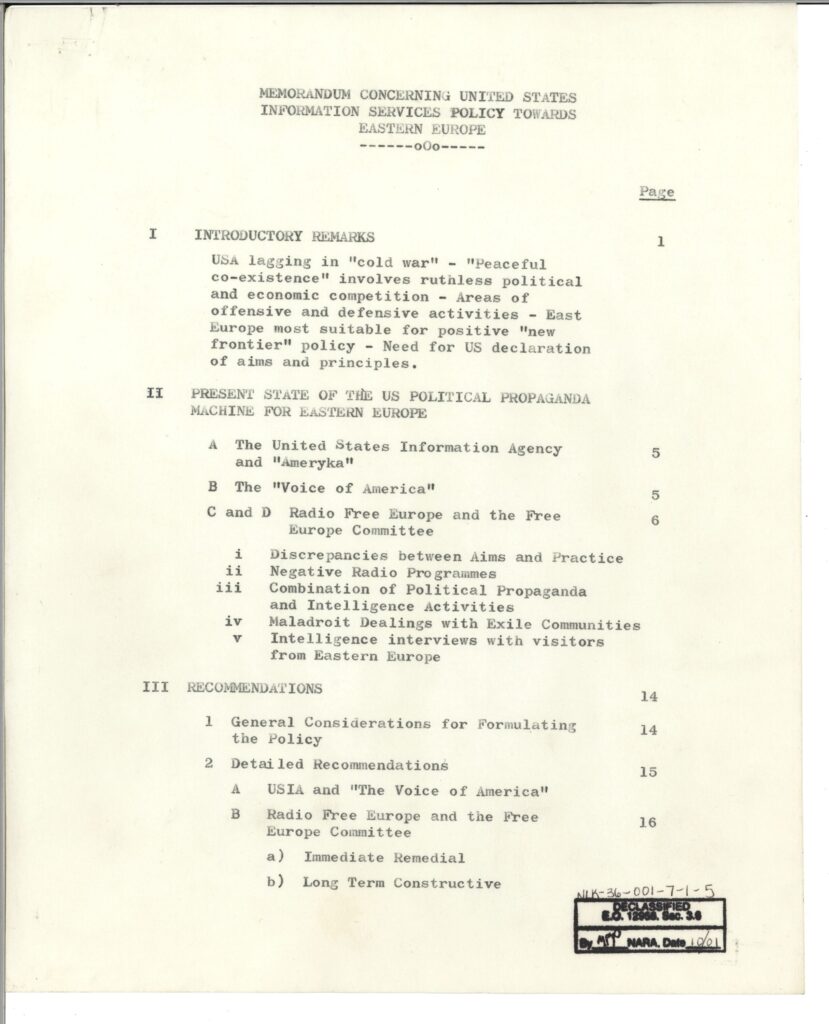

In early 1961, President Kennedy authorized a confidential internal review of U.S. information policy toward Eastern Europe. The resulting memorandum —“Memorandum Concerning United States Information Services Policy Toward Eastern Europe” — was circulated privately within the White House and among senior officials, including the United States Information Agency. White House aide Theodore C. Sorensen forwarded the memorandum to Robert C. Sorensen for comment and informed him that Thomas (“Tom”) Sorensen, then serving in a senior policy role at USIA under Edward Murrow, had been asked to prepare a parallel analysis for the President.46

The authorship of the analytical sections is not explicitly identified, a common feature of internal White House policy papers of the period. While Theodore Sorensen’s role was that of a conduit and presidential adviser, the memorandum appears to reflect the views of USIA officials skeptical of both surrogate broadcasting and confrontational political messaging toward the Soviet Bloc.

The critique of the Voice of America was blunt. The memorandum asserted that “the American propaganda machine compares very modestly with that of the Soviet Union” and that its “costs are out of all proportion to the unimpressive results achieved,” contributing, in the author’s view, to “the recent decline of American prestige in the world.”

VOA’s broadcasts were described as “stiff, stuffy and completely detached from the life of the countries to which they are broadcast,” and Eastern European listeners were said to complain that VOA programs were “dull and monotonous,” the product of “a bureaucratic approach and a lack of journalistic touch.”47

The memorandum also criticized VOA’s personnel policies, noting that naturalized Americans and political exiles—people “with an expert knowledge of their countries or at least a natural understanding of their countrymen’s reactions and ways of thinking” — were “by virtue of their birth excluded from editorial and advisory posts” and used primarily as translators.48 Ironically, this criticism echoed concerns later raised by VOA’s own foreign-language services, whose broadcasters were refugees from communism and possessed precisely the lived experience that many VOA English-language editors lacked.

The assessment of Radio Free Europe was even more severe. The memorandum declared that RFE “has fallen very far short of the noble ideals it was supposed to propagate” and claimed that it had “a poor reputation in Europe generally, and has no moral authority behind the Iron Curtain,” despite being widely heard because of its powerful transmitters.49 Its programming was characterized as “purely negative,” consisting of “constant bickering and monotonous attacks on the inefficiency and shortcomings of the Communist regimes,” which the author argued could not lead to constructive political change.50

From the perspective of Radio Free Europe’s documented performance—especially in Poland under the leadership of Jan Nowak-Jeziorański, where RFE urged restraint to avoid Soviet military intervention and earned deep public trust — these claims appear exaggerated or demonstrably false. Listeners in Poland and elsewhere understood RFE’s connection to the United States, valued its pluralism, and respected its independence. The memorandum’s recommendations — to curtail RFE’s autonomy, strip it of bold political commentary, and subordinate it to diplomatic and cultural exchange programs — reflected a vision favored by some U.S. diplomats who viewed surrogate broadcasting as an obstacle to engagement with communist regimes.

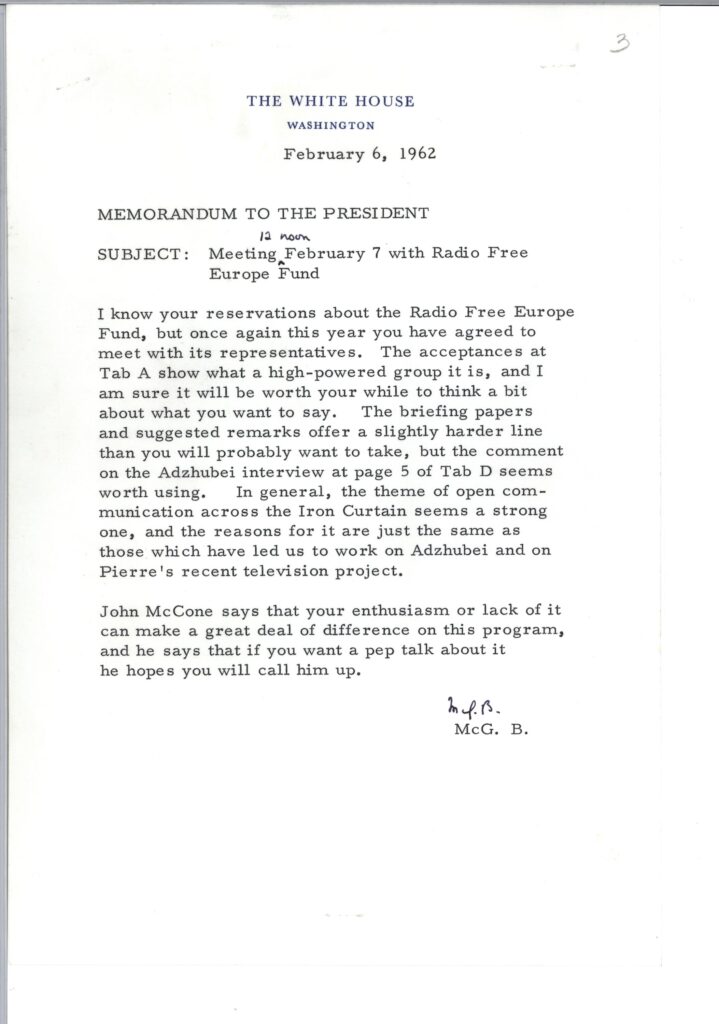

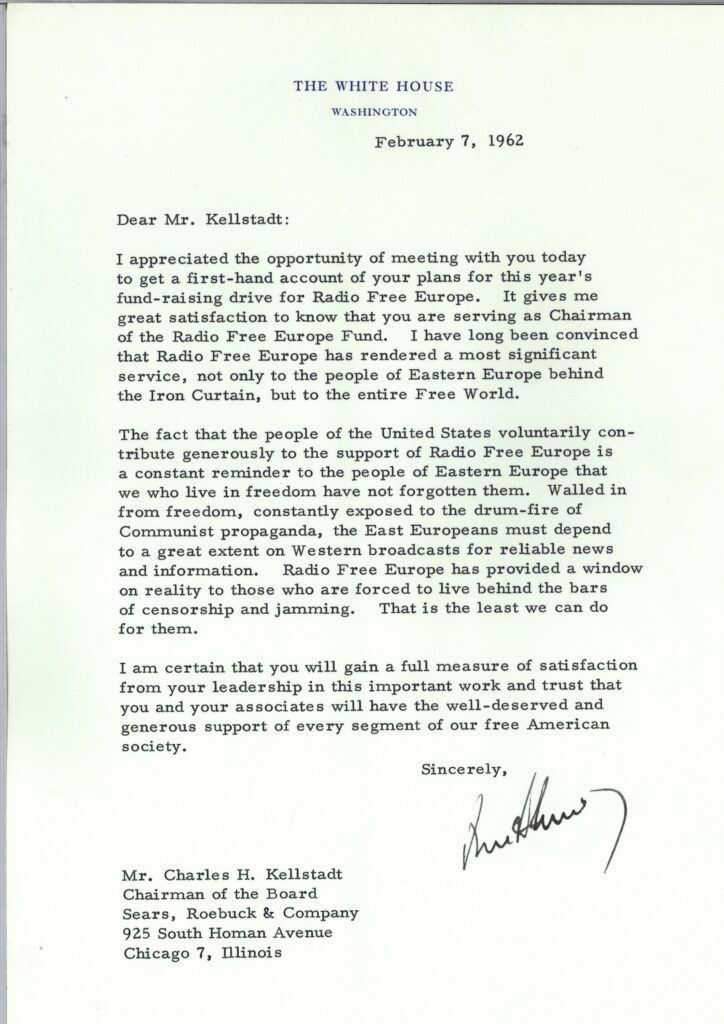

Despite internal criticism of Radio Free Europe within parts of the Kennedy administration, President Kennedy’s own actions demonstrate that he ultimately rejected proposals to curtail RFE’s mission and did not adopt the memorandum’s central recommendations. His continued public support for the Radio Free Europe Fund and his refusal to weaken RFE’s mission suggest that, while he welcomed internal debate, he did not accept the premise that surrogate broadcasting was counterproductive. A White House memorandum of February 6, 1962, prepared by National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, acknowledges the President’s reservations about the Radio Free Europe Fund, yet emphasizes that Kennedy had again agreed to meet with its leadership and that his attitude would “make a great deal of difference” to the program’s success.51 The following day, Kennedy wrote personally to Charles H. Kellstadt, Chairman of the Radio Free Europe Fund, praising RFE for providing “a window on reality” to people living behind the Iron Curtain and affirming that its work was “the least we can do for them.”52

These documents confirm that while John F. Kennedy understood the political sensitivities surrounding Radio Free Europe’s public fund-raising role, he did not hesitate to support its core mission. On the contrary, Kennedy deliberately chose Edward R. Murrow to implement his policy of engaging the Soviet Union and international communism through an intensified war of ideas. Murrow’s own actions as USIA director — together with his public speeches and classified memoranda —demonstrate that he was not merely compliant with this approach but one of its most energetic advocates. Far from opposing the use of U.S. international broadcasting as an instrument of foreign policy and ideological competition, Murrow actively promoted harder-hitting content when he believed existing programming failed to confront Soviet propaganda forcefully enough. The documentary record thus contradicts later claims that Murrow, in his government role, favored a restrained or purely non-ideological conception of international broadcasting.

As historian Arch Puddington — a former deputy director and head of the New York Bureau of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty — later observed, President Kennedy “had vowed to escalate the struggle against communism,” while Robert F. Kennedy was “an enthusiastic supporter of RFE.” The administration, Puddington wrote, “announced its intention to engage the Soviet Union in an aggressive war of ideas all over the globe.”53

Puddington’s empirical findings also directly contradict the Sorensen memorandum’s portrayal of RFE as ineffective and distrusted. He noted that “RFE clearly stood as the most popular foreign broadcast service in the Eastern bloc,” citing a 1959–60 survey conducted by European research institutes showing RFE with “far more regular listeners than either the BBC or the VOA.” By contrast, “the VOA had suffered a notable decline in listenership since the Hungarian Revolution,” which he attributed to management restrictions on political broadcasting and a programming emphasis on “world news, American culture, and jazz music.”54

When Regime Narratives Travel Upward: Disinformation, Diplomacy, and Policy Blind Spots

A further dimension of the 1961 policy debate merits attention, not because it was decisive, but because it illustrates a recurring structural vulnerability in U.S. foreign policy making: the ability of authoritarian regime narratives to migrate — often indirectly — into American internal analysis.

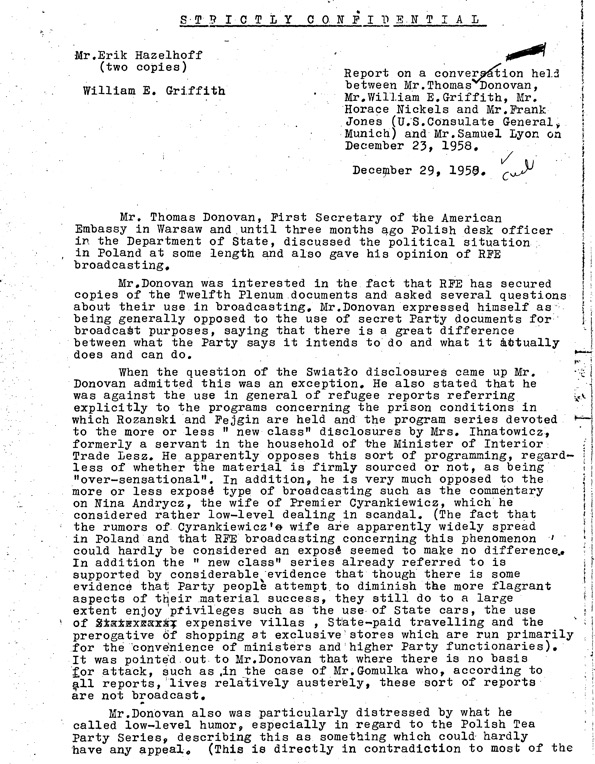

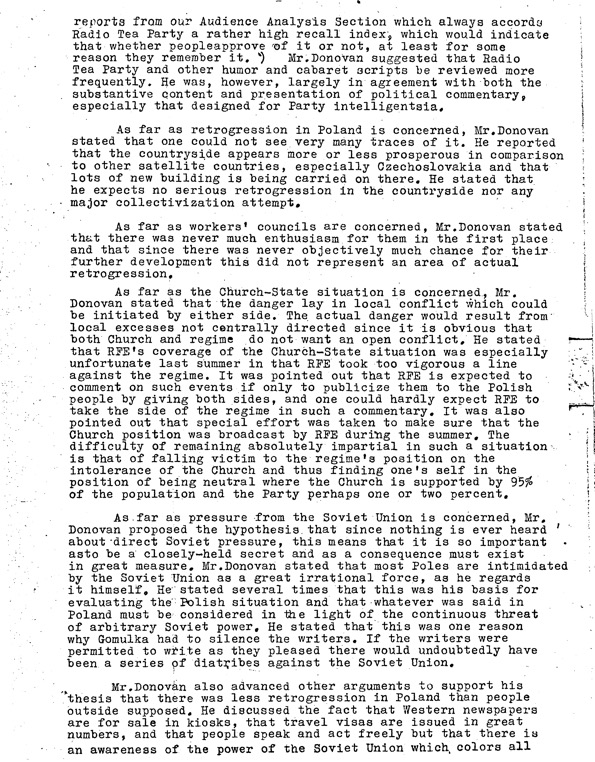

Several of the internal memorandum’s most severe criticisms of Radio Free Europe’s Polish Service closely resembled arguments advanced earlier by officials of the Polish communist regime and repeated in U.S. Embassy Warsaw reporting during the late 1950s. These claims portrayed RFE as politically irresponsible, dominated by émigrés detached from realities inside Poland, exaggerating repression, and obstructing prospects for gradual reform through diplomatic engagement. Such themes featured prominently in the reporting and advocacy of Ambassador Jacob D. Beam and his political officer Thomas Donovan, who urged that RFE’s Polish broadcasts be curtailed or eliminated in the interest of improving official U.S.–Polish relations.

That these embassy-originated criticisms were contested within the U.S. government at the time is documented in a declassified 1959 Central Intelligence Agency assessment responding directly to Ambassador Beam’s critique of Radio Free Europe. In that memorandum, CIA official Cord Meyer acknowledged isolated weaknesses in some RFE Polish broadcasts but rejected the Embassy Warsaw’s overall negative assessment as overstated and strategically misguided. The CIA analysis emphasized that RFE remained a “responsible and reliable source of news and commentary,” that allegations of systematic exaggeration were unsupported, and that embassy complaints closely tracked Polish regime sensitivities rather than listener realities. The document further warned that suppressing or fundamentally restructuring RFE’s Polish Service in response to such complaints would risk depriving the United States of one of its most effective channels to the Polish population.

What is striking is not that such criticisms originated in Warsaw, where the communist authorities had a clear interest in neutralizing RFE, but that similar formulations later appeared in an internal White House policy review forwarded in early 1961 to Theodore C. Sorensen. By the time these arguments reached senior policymakers, they no longer appeared as regime talking points but as ostensibly pragmatic assessments aligned with diplomatic caution and bureaucratic preference.

A declassified 1958 Radio Free Europe internal memorandum documenting a conversation between Donovan and RFE’s chief political adviser, William E. Griffith, captured the circulation of these arguments at the time.55 The document records embassy claims that RFE distorted political conditions in Poland and obstructed diplomatic objectives — assertions RFE leadership regarded as both factually incorrect and politically naïve.

The communist authorities in Warsaw had a clear interest in neutralizing RFE, but that similar formulations later appeared in a White House policy review intended to guide the new Kennedy administration. Radio Free Europe’s response rested on empirical evidence rather than theory. Its Polish Service consistently avoided incitement, discouraged premature confrontation, and emphasized national continuity, cultural identity, and factual reporting. Under Jan Nowak-Jeziorański’s leadership, RFE urged restraint during moments of crisis precisely to avoid provoking Soviet military intervention. Audience research, listener correspondence, and independent surveys contradicted claims that RFE lacked credibility or moral authority in Poland.

Senior U.S. officials ultimately accepted this judgment. Ambassador Beam’s campaign against RFE failed, as did later efforts to subordinate surrogate broadcasting to official diplomacy. Vice President Richard Nixon, after witnessing the extraordinary public response to his 1959 visit to Warsaw—made possible in part by Radio Free Europe’s reporting — reportedly reminded Beam that an American ambassador’s duty was not only to deal with a communist government but also to maintain a relationship with the people living under it.56

Seen in this light, the Sorensen memorandum illustrates less a failure of judgment than a persistent institutional tension. U.S. diplomats and public diplomacy officials often hoped that moderation, cultural exchange, and engagement might soften authoritarian systems from within. Surrogate broadcasters, informed by refugee experience and audience feedback, tended to regard such hopes as unrealistic so long as those regimes remained fundamentally illegitimate and dependent on Moscow. Where these perspectives collided, foreign disinformation could find an opening — not through deception alone, but through alignment with preexisting assumptions of high-level U.S. government officials and advisors, a dynamic that has reappeared in different forms in later eras, including contemporary Russian influence efforts aimed at shaping Washington’s responses to Moscow’s war against Ukraine.

These documents allow readers to trace this process directly. They show how arguments originating with a communist regime entered embassy discourse, migrated into internal U.S. policy debates, and were ultimately tested against empirical evidence and political judgment. They also help explain why President Kennedy, despite welcoming critical analysis, declined to accept recommendations that would have weakened Radio Free Europe’s independence or silenced one of the most effective voices reaching Poland behind the Iron Curtain.

Jazz, Diplomacy, and Influence: The Beam Critique, Radio Free Europe, and a Polish Intelligence Operation

The declassified CIA memorandum rejecting Ambassador Jacob D. Beam’s critique of Radio Free Europe offers more than a bureaucratic disagreement over broadcasting policy. Read in context, it illuminates a broader and more troubling pattern: the vulnerability of U.S. diplomatic and information officials to foreign influence operations that aligned neatly with their own institutional preferences and assumptions.

By the late 1950s, Ambassador Beam and some officials within the State Department and the United States Information Agency had become convinced that what would most effectively undermine communism in Poland, the Soviet Union, and other Eastern Bloc countries was not surrogate political broadcasting but cultural engagement—above all, the Voice of America’s jazz programs hosted by Willis Conover. Beam argued as early as 1957 that “a good case can be made that R.F.E. should be dispensed with in favor of a modified Voice of America,” a view echoed in varying forms by diplomats who regarded Radio Free Europe as an obstacle to engagement with communist governments.

This assessment rested on a serious misreading of social and political realities. While Conover’s Jazz Hour held undeniable symbolic value, its actual reach in Poland during the 1950s was limited. The program was listened to primarily by a relatively small circle of English-speaking young intellectuals and artists. It enjoyed far greater resonance in the Soviet Union, where American jazz had been banned for longer and where English-language cultural broadcasts carried a different weight. In Poland, by contrast, the communist authorities had largely lifted restrictions on American music by the mid-1950s. Jazz and other Western music were already being played on Polish state radio by the end of the decade.

Yet Conover’s 1959 visit to Poland — enthusiastically embraced by jazz musicians and fans — appears to have been leveraged as political proof that cultural diplomacy alone could succeed where surrogate broadcasting was supposedly unnecessary. Declassified records and later Polish archival findings suggest that this visit was closely monitored by the Polish communist intelligence service and secret police, which sought not merely to observe Conover but to exploit the occasion to influence U.S. diplomats in Warsaw. The broader objective, as reconstructed from multiple sources, appears to have been to encourage Washington to censor or shut down Radio Free Europe’s Polish Service.

Polish media reports, drawing on files held by the Institute of National Remembrance, indicate that the surveillance of Conover was part of a wider influence and intelligence operation targeting the American Embassy in Warsaw in the late 1950s.57 These efforts coincided with diplomatic pressure from Ambassador Beam and others who hoped that eliminating RFE would facilitate cultural exchanges and détente with the Polish communist regime.

One reported — but not fully documented — figure in this milieu was Mira Michałowska (formerly Mira Złotowska), a former wartime Office of War Information and Voice of America Polish Desk editor who later returned to Poland, married a high-ranking diplomat, and reportedly enjoyed access to senior U.S. officials in Warsaw. While direct evidence of her role remains incomplete, contemporary records and later accounts suggest that she may have served — wittingly or unwittingly — as an informal channel through which Polish regime perspectives reached American diplomats. If so, this would represent a striking continuity with earlier wartime patterns in which individuals associated with U.S. international broadcasting became conduits for foreign influence.

The CIA memorandum rejecting Beam’s critique is therefore significant not only for defending Radio Free Europe but for implicitly recognizing the strategic danger of such influence. Intelligence officials acknowledged that RFE programming could be imperfect, but they rejected the notion that surrogate broadcasting lacked credibility or popular trust. They understood that cultural diplomacy and music, while valuable, could not substitute for sustained political reporting and commentary aimed at mass audiences.

Indeed, the historical record demonstrates that it was not jazz that ultimately undermined communist rule in Poland. The industrial workers and farmers who formed the backbone of the Solidarity movement did not, for the most part, speak English or follow American jazz. They were influenced by Western radio’s political reporting — especially Radio Free Europe’s Polish Service — which provided uncensored news, pluralistic debate, and moral clarity during moments of crisis.

Willis Conover remains an enduring symbol of American cultural influence and deserves his place in Cold War history. But elevating his programs into a substitute for political broadcasting reflects a persistent tendency among some public diplomacy practitioners and scholars to romanticize culture while downplaying the central mission of international broadcasting. Voice of America was fortunate to have Conover at a critical moment, but it never again developed a comparable musical figure with mass appeal. By contrast, Radio Free Europe’s Polish Service produced popular and influential music programming alongside hard political reporting, integrating culture into a broader strategy rather than treating it as a replacement.

Seen in this light, the Beam critique and the Polish intelligence operation surrounding Conover’s visit offer a cautionary tale. Foreign disinformation and influence do not always succeed through outright deception. They are often most effective when they reinforce existing preferences within target institutions — here, the diplomatic desire for engagement, cultural exchange, and the reduction of politically confrontational broadcasting. The CIA’s rejection of Beam’s arguments stands as an early recognition of this danger, one with implications that resonate well beyond the Cold War.

↑ Back to top · ▶ Back to Murrow audio

V. U.S. Broadcasting Strategy After 1945 – What Changed, What Didn’t

Redirection of resources to counter rather than support Soviet propaganda initially began under the Truman administration, which took the first steps to reduce the influence of pro-Moscow radicals within VOA. However, the momentum to transform VOA gradually slowed during the Eisenhower years. President Kennedy strongly supported U.S. government international broadcasting but — facing Cuba, Berlin, and decolonization — focused much of his attention on Latin America and Africa. Later, under Presidents Nixon and Ford, the White House — acting largely through Henry Kissinger — chose not to expand U.S. government broadcasting to the Soviet Bloc, not because of sympathy for communism, but to preserve détente and avoid jeopardizing negotiations on Vietnam and nuclear arms. It was during this period that USIA, at the White House’s direction, ordered a ban on the Russian Service’s interviewing of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.58 In contrast, the VOA–RIAS Christmas broadcast and Murrow’s National Press Club speech present a much earlier moment — one of stronger institutional confidence and a clearer commitment to countering Soviet propaganda directly.

To this day, Cuba remains a communist dictatorship. The eventual fall of communism in East-Central Europe began in Poland under the strong moral influence of the Catholic Church. Mark G. Pomar, a former director of Russian-language programming at Radio Liberty and at the Voice of America, observed that prior to Ronald Reagan’s presidency, “if one were to search through publications or government documents about VOA during the Cold War, one would be hard-pressed to find any explicit references to religious programming.”59 Still, even though religion is largely absent from the VOA–RIAS narration – apart from Christmas music – the USIA – VOA – RIAS program clearly brought a measure of hope to listeners behind the Iron Curtain, especially if VOA foreign-language services reused segments in their own languages. This regional comparison shows why messages of hope — whether religious or secular — carried geopolitical weight.

Murrow, Regime Change in Cuba, and the Tone of VOA Broadcasting to the Soviet Union

As director of the United States Information Agency, Edward R. Murrow was an explicit supporter of regime change in Cuba and intervened repeatedly to make Voice of America coverage of Cuba more forceful and confrontational. At the same time, he occasionally voiced objections to specific Kennedy administration policies — most notably restrictions on travel by Americans to the island — demonstrating that his support for administration objectives did not preclude disagreement over tactics.60

Contrary to the later image promoted by some former USIA and VOA officials, editors, and reporters, Murrow did not believe that the Voice of America should function as an autonomous or detached journalistic institution. He regarded VOA as an authoritative voice of the United States government, one that was expected to support the policies of the President and his administration. As Murrow told a Miami Herald reporter, he did not object to being described as a “propagandist” so long as “the propaganda is based on the truth.”61

President Kennedy appointed Edward R. Murrow a member of the National Security Council, yet he did not inform him in advance about the Bay of Pigs operation. Murrow learned of the planned CIA action in Cuba from his deputy, Donald M. Wilson, who in turn had been alerted by Polish-born New York Times foreign correspondent Tad Szulc, later credited with breaking the story of the invasion.62 Despite being sidelined at such a critical moment, Murrow did not resign from USIA. On the contrary, he publicly reaffirmed his full support for President Kennedy’s Cuba policy and for an intensified American information offensive.

Speaking to journalists at the National Press Club on May 24, 1961, Murrow declared unequivocally that the United States was no longer content to remain on the defensive in the ideological struggle with communism:

We are taking the offense in this war of ideas. We shall be more alert in exposing Communist techniques and tactics. Distortion and duplicity about this land will not go unanswered.63

Murrow left no ambiguity about how USIA and the Voice of America should describe Fidel Castro’s regime. Rejecting euphemism and moral relativism, he stated that American international broadcasters must make clear to their audiences:

We shall ask them [USIA and VOA audiences] to recognize the nature of his totalitarian dictatorship, his betrayal of the ideals of the revolution that brought him to power, his suppression of basic human liberties, his treason to the ideals of civilization, and his atrocities, his calculated reliance on the Sino-Soviet bloc and the danger that this threatens to free institutions in the Western Hemisphere.64

In light of these explicit statements, it is difficult to reconcile Murrow’s own record with later claims — advanced by some former USIA and VOA officials—that he would have tolerated the glorification of revolutionary violence, the uncontextualized dissemination of anti-American imagery or the use of U.S.-funded media to run one-sided electoral campaign commercials against a sitting American president. Under Murrow’s leadership, it would have been unthinkable for USIA or VOA to praise figures such as Che Guevara, distribute material showing the burning of American flags without critical context, or function as platforms for domestic political campaigning while invoking journalistic independence as a shield against oversight during the last two decades.

Murrow understood that journalists employed by the U.S. government and funded by American taxpayers did not occupy the same role as private reporters in the domestic press. Their mission, as he defined it, was to tell the truth — but to do so in the service of democratic values, American foreign policy, and a clear moral understanding of the totalitarian adversaries the United States confronted.

Murrow was notably more hawkish in his expectations of VOA programming directed to and about Cuba than in broadcasts aimed directly at the Soviet Union. With respect to VOA’s Russian-language output, he accepted the argument — advanced by Foreign Service officers within USIA — that the Soviet audience required a different approach. He supported an increased emphasis on cultural programming and believed that VOA’s Soviet Division needed both a strategic reset and new leadership.65

This shift became visible after Murrow’s tenure. A short item in the conservative weekly Human Events reported on February 1, 1964, that Alexander Barmine — a former Soviet general and outspoken anti-communist — had been removed from his position as head of VOA’s Russian desk. According to the column, Barmine had fallen into disfavor with USIA superiors for inserting what they viewed as “provocative” programs into broadcasts beamed to the Soviet Union. The same report noted that Murrow’s successor as USIA director, Carl Rowan, planned to expand “non-controversial radiocasts to Russia.”66

Foreign Service Officer Hans H. Tuch, who served in multiple senior roles at both USIA and VOA, later confirmed Murrow’s personal involvement in Barmine’s removal. In a 1989 oral history interview, Tuch stated that Murrow had supported transferring Barmine from his VOA Russian Service post to a largely marginal position at USIA headquarters. According to Tuch, Murrow wanted “an American with experience in the Soviet Union, an American officer who spoke Russian with recent experience,” to head the VOA Soviet Division.67

Mark Pomar, former assistant director of the Russian Service at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and former director of the USSR Division at the Voice of America, wrote in his Cold War Radio book that when he joined VOA, “Barmine was long gone, but stories about him still circulated. He had been feared by many of the old timers but also deeply admired for the way he stood up to American management and supported an independently minded Russian Service.”68

Taken together, these episodes further undermine the later portrayal of Murrow as a defender of a restrained or purely non-ideological Voice of America. His record as USIA director shows a pragmatic and strategic actor — willing to intensify information warfare where he deemed it effective, cautious where he believed it was not, but consistently committed to the view that U.S. international broadcasting was an instrument of national policy rather than an independent journalistic enterprise.

One Small Inaccuracy

Murrow, or those who drafted his narration for the VOA Christmas broadcast about RIAS, included one somewhat misleading statement: that for most listeners in the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany, RIAS broadcasts “constituted their only link with the free world.” In reality, many East Germans could listen to radio stations broadcasting from the Federal Republic of Germany, and in some areas of the GDR they could even receive West German television. Still, RIAS broadcasts were a powerful symbol of American commitment to the freedom of West Berlin and to the eventual restoration of democracy in the Eastern Bloc.

This clarification does not diminish Murrow’s narrative power but helps situate his rhetoric in reality. Some VOA journalists, USIA officials, and officials of USIA’s successor agencies often exaggerated the size of their audience and the impact of their programs, especially English-language broadcasts, which had a limited audience and limited effectiveness in countering Soviet propaganda. The largest audiences for VOA were for foreign language broadcasts to Easter and Central Europe. USIA and VOA leadership tended to highlight English-language broadcasts, partly to justify maintaining a large American-staffed newsroom. Murrow placed a number of his former CBS colleagues in USIA and VOA jobs.

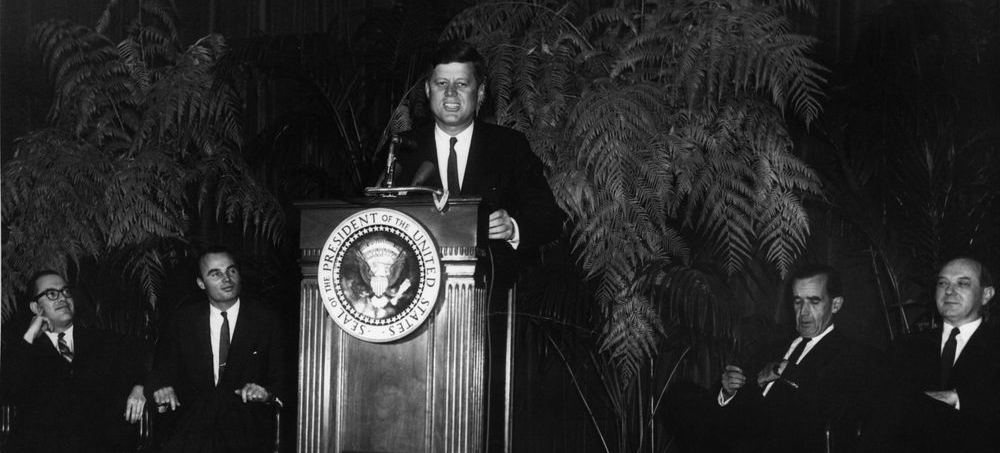

Ich bin ein Berliner

While Murrow’s 1961 RIAS Christmas introduction offered hope and human connection across the Wall, another moment of symbolic communication came more than two years later. On June 26, 1963, President John F. Kennedy delivered his now-famous Ich bin ein Berliner speech in West Berlin, declaring solidarity with the people of the divided city nearly two years after the Wall’s construction.

The speech — aimed as much at the Soviet Union as at West Berliners — affirmed that “all free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin,” and concluded with Kennedy’s emphatic “Ich bin ein Berliner” (I am a Berliner).”  Kennedy’s words gave a morale boost to West Germans living under the shadow of the Wall and became one of the most iconic moments of Cold War public diplomacy.

Kennedy’s speech was developed over weeks of preparation. His chief speechwriter and presidential adviser, Ted Sorensen, played a significant role in drafting the address, though Sorensen himself later wrote that the famous line may ultimately have originated with Kennedy or emerged in rehearsal. Kennedy also practiced the German phrase with Robert H. Lochner, an interpreter and former RIAS official who helped Kennedy with pronunciation and phonetic cues.69

Edward R. Murrow did not have a direct role in drafting or delivering the Ich bin ein Berliner speech, and there is no evidence that he was physically present for it. Nonetheless, this moment—like the RIAS broadcast in 1961 — underscores the importance of symbolic speechmaking and messaging in U.S. efforts to counter communist domination and affirm democratic identity during the Cold War. His reported remark that even a child could have stopped it (“a little girl with a lollypop“) expressed moral outrage, but it also invites sober historical reflection.70 It is unclear whether anything short of massive East German civilian resistance — which did not materialize — could have altered the course of events, as eventually occurred in Poland during the Solidarity movement, supported morally by Pope John Paul II and, decisively, by President Ronald Reagan. Even then, neither Solidarity nor Reagan advocated violent resistance, and the risk of Soviet military intervention — with consequences comparable to Hungary in 1956 — remained real.

Western military intervention in Berlin might have changed history — or led to catastrophe. The unanswered question underscores a recurring lesson of the Cold War: public diplomacy and broadcasting can illuminate truth, moderate repression, and stiffen resolve over time, but they cannot substitute for political power, internal will, or the strategic and historical-political realities on the ground. This is not a judgment on any nation or culture, but an observation that history, institutions, and trauma of occupation or colonialism shape what a society can or cannot risk at any given moment.

Kennedy’s View of U.S. Broadcasting – VOA vs. Radio Free Europe

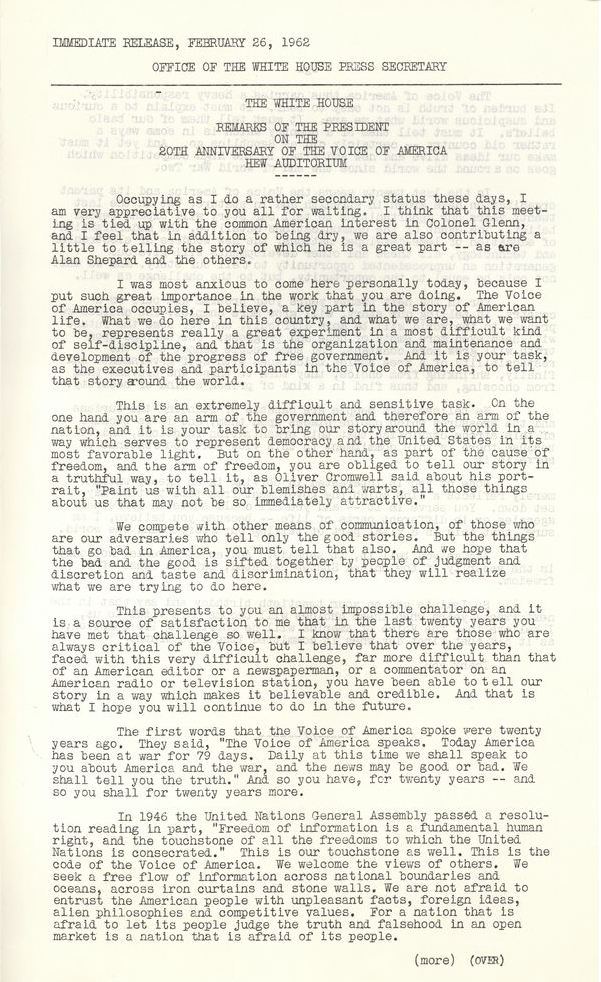

President John F. Kennedy’s public remarks on U.S. international broadcasting help clarify the policy environment in which Murrow operated. On February 26, 1962, in a speech marking the 20th anniversary of the Voice of America, Kennedy praised VOA’s commitment to accuracy while emphasizing that its mission differed fundamentally from that of private American media:

🎧 LISTEN FIRST

President John F. Kennedy delivers remarks at the 20th anniversary observance of the Voice of America (February 1962).