Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

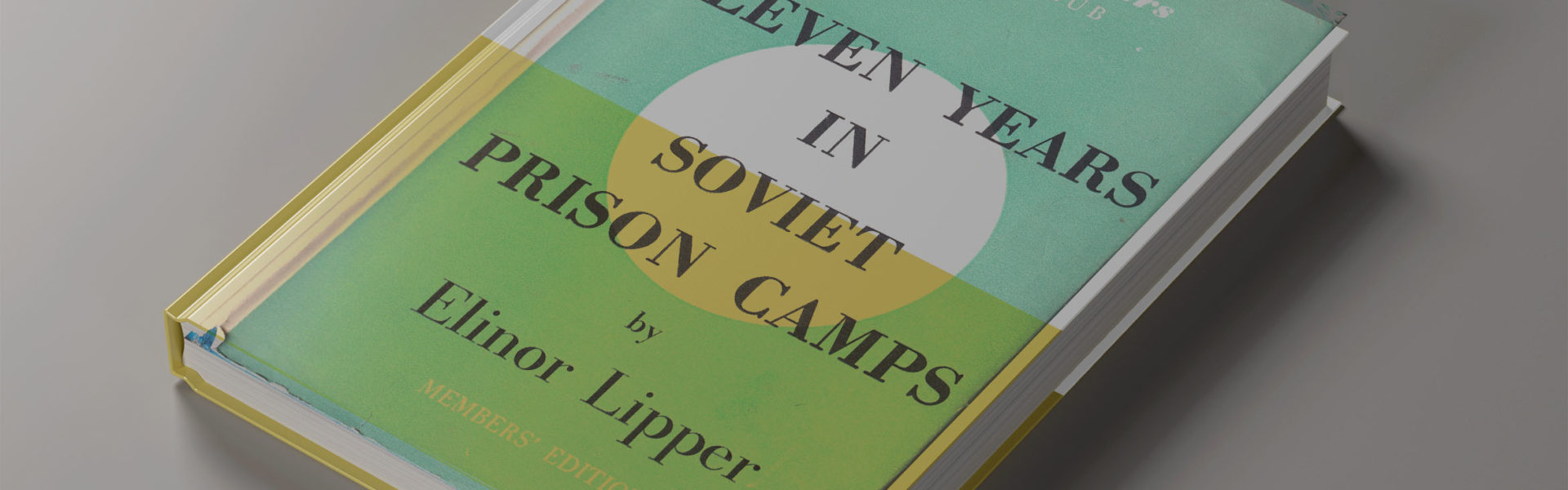

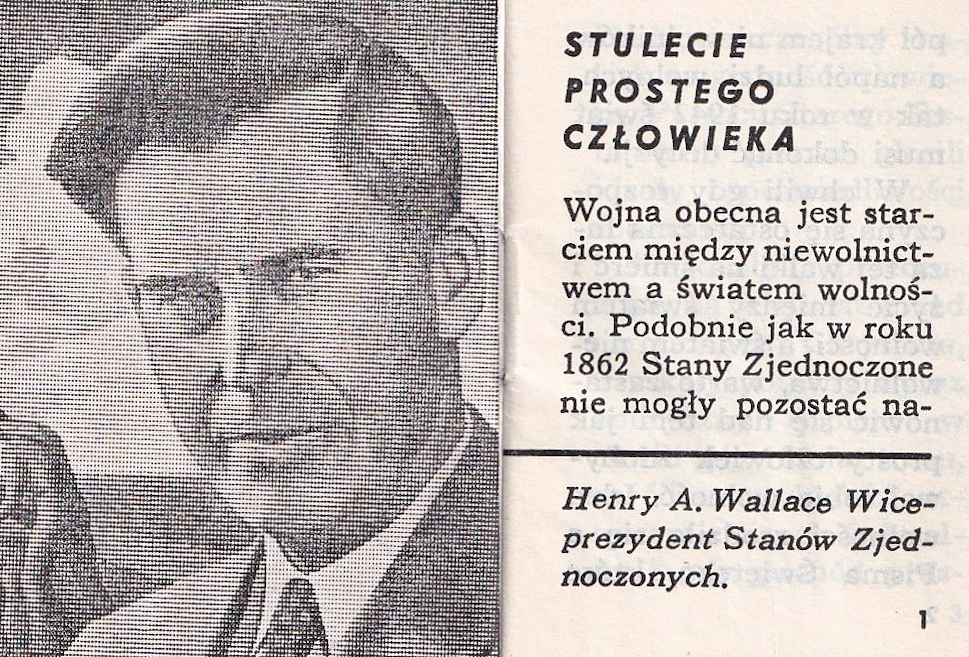

The March 25, 1951 Sunday edition of the New York Times had a review by journalist and writer Harry Schwartz of Elinor Lipper’s book Eleven Years in Soviet Prison Camps, in which the former Western political prisoner in Russia debunked various Soviet propaganda lies about the infamous Kolyma gold mines in the Gulag system of slave labor. What some discerning New York Times readers may have learned from the article was that Americans have been deceived about the Soviet Union by some of their own politicians, government experts, and journalists. Included in the German-Jewish ex-Communist’s book was the comparison of her experience as a Gulag prisoner with the pro-Soviet disinformation and propaganda published by the Office of Information (OWI) and Voice of America (VOA) official Dr. Owen Lattimore in his 1944 article in the National Geographic Magazine. In her book and in its condensed version in the June 1951 issue of Reader’s Digest, Lipper showed how U.S. Vice President Henry A. Wallace, who had visited Kolyma accompanied by Owen Lattimore as his translator (in Mongol and Chinese) and advisor, was duped by Soviet officials in a deliberate scheme to hide the slave labor camps and their prisoners who worked there to extract gold, and where they died in large numbers from malnutrition, illnesses, and being exploited beyond human endurance.

Whether Dr. Lattimore was also duped in the same manner as Wallace or was aware of the Soviet deception and chose to hide it from the Vice President is less clear. It was President Roosevelt who had told Wallace to take Lattimore with him on his trip to Soviet Russia and China as “one of the world’s great experts on the problems involving Chinese-Russian relationships.”1 In 1941, FDR appointed Professor Owen Lattimore, who advocated for a stronger Soviet and Communist Party role in China, to serve as U.S. advisor to Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek, a position he held for one and a half years.

Wallace described Lattimore in his 1946 book about his trip to Russia and China as “a statesman in Pacific affairs and a scholar in the Chinese language” and wrote that he was fortunate to have Lattimore’s advice.2 Quoting Lattimore’s political and cultural observations about Russia, Central Asia, Mongolia, and China extensively in his book, Wallace proudly pointed out that his advisor “has reached conclusions on a variety of Sino-Soviet problems that trouble American minds.”3 Most of Lattimore’s conclusions favored the Soviet Union and the Chinese Communists and matched Wallace’s political preferences and views.

The 1943 Official Register of the United States listing persons occupying administrative and supervisory positions in the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of the Federal Government, and in the District of Columbia Government, as of May 1, 1943, showed Owen Lattimore as Pacific Bureau Director at the Office of War Information San Francisco Regional Office, and thus responsible for Voice of America broadcasts to Asia, including China. In 1944, Lattimore was named OWI deputy director in Washington in charge of all Pacific programs but resigned at the end of the year to return to Johns Hopkins University.

Because of the subsequent controversy over his role in the U.S. government’s wartime information agency, Lattimore found himself among several founding fathers of the Voice of America, whose names have been written out later from VOA’s official history. OWI and VOA officials and journalists like him eagerly embraced Russian disinformation and supported Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin during World War II and, in some cases, even after the war’s end. After the beginning of the Cold War, their names started to disappear from books and articles about the Voice of America to prevent further embarrassment and damage that their past pro-Soviet and pro-communist Chinese sympathies and associations could inflict on the U.S. government broadcaster and its federal agency in charge of public diplomacy agency.

In the English-language edition of her book, Elinor Lipper devoted one subchapter to Vice President Henry A. Wallace’s visit to Kolyma and another to Owen Lattimore’s article about what the two Americans saw in Soviet Russia. She noted in her book that Dr. Owen Lattimore was a professor at Johns Hopkins University “who represented the Office of War Information” as a member of Vice President Wallace’s delegation, which conducted a tour of Soviet Siberia in May and June 1944. The Office of War Information was the federal U.S. government agency that produced Voice of America broadcasts for overseas audiences during World War II.

Elinor Lipper was a young, idealistic communist activist whose parents were German Jews. She had traveled to the Soviet Union in 1937 to work for a Soviet publishing company and was promptly arrested on suspicion of counterrevolutionary activity. At the time of Wallace’s visit, she was a political prisoner in the Kolyma forced labor camps. Some of her co-prisoners were German Communists and other refugees from Hitler’s Germany, including Jews, but the vast majority of slave laborers were Russians, those accused of political crimes, and common criminals.

Among the prisoners were also American citizens, American Communists who emigrated to the Soviet Union in the 1930s to support Communism, and ordinary American engineers and workers looking for work in Russia during the Great Depression who were later arrested by the Soviet secret police. Those who were not executed were sent to the Gulag. As documented extensively by British writer and filmmaker Tim Tzouliadis in his book The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin’s Russia, published in 2008, they were abandoned by the U.S. government and most of its diplomats in Moscow, who had made little effort to get them released. “In fear for their lives, American emigrants were turned away by their diplomats, often on the flimsiest of grounds.” If their passports had been lost or stolen by the NKVD, U.S. consular officials told them they would have to undergo a lengthy investigation. If they did not bring a photograph or the money for the application fee, they were told to come back later. Many were arrested immediately after leaving the embassy and were never heard from again.4

Among the disappeared Americans were hundreds of autoworkers who emigrated with their families from the United States to Russia to build automobiles at the plant in Nizhni Novgorod constructed under the forty-million-dollar deal signed with the Kremlin in May 1929 by Henry Ford.5 The story of the “captured Americans,” many of whom had been tricked into accepting Soviet citizenship or had their American passports confiscated, never became widely known in the United States. Writing about the American reporters in Moscow, including the New York Times‘s Walter Duranty, Greek-born, Oxford-educated British journalist and writer Tim Tzouliadis observed that not wanting their visas revoked and being expelled and subjected to official Soviet censorship, they “began to lose all measure of their critical faculties, lapsing unto a stupefying form of self-censorship.” He correctly noted that their continued employment in Moscow as American journalists “depended on the approval of the Soviet authorities.”6

Elinor Lipper reported seeing Polish, Latvian, German, Hungarian, and Romanian Gulag prisoners but did not mention Americans. Tzouliadis, whose work has been featured on BBC, NBC, and National Geographic television, wrote that in the first eight months of 1931 alone, the Soviet trade agency in New York received more than one hundred thousand applications from Americans hoping to work in Soviet Russia. The author noted, “It was the least-heralded migration in American history.7

One prominent African-American, Tzouliadis wrote about in his book was Lovett Fort-Whiteman, who had gone to the Soviet Union in 1924 and became a Comintern agent. He applied to the Soviet authorities for permission to return to the United States, but his exit visa request was refused, and he was denounced as a “counterrevolutionary” by a lawyer from the Communist Party USA and sent to a labor camp in Kazakhstan.8 According to a witness, he had been beaten for not meeting his work quota, his teeth had been knocked out, and he died of starvation in January 1939.9. Two other African-Americans, Associated Press journalist Homer Smith Jr. and engineer toolmaker Robert Robinson avoided being sent to the Gulag but spent years trying to get permission to leave the Soviet Union.10 Robinson accepted Soviet citizenship but later deeply regretted his decision. He wrote in his autobiography, Black on Red: My 44 Years Inside the Soviet Union, published in 1988 after his return to the United States, that every single Black he knew in the early 1930s who, like him, became a Soviet citizen “disappeared from Moscow within seven years.”11 Only the lucky ones were sent to the Gulag. The others were shot, Robinson wrote.12

The State Department knew about the American citizens who had disappeared in Russia and should have told Vice President Wallace about them. As a scholar and U.S. government’s expert on propaganda, whose job was to advise Wallace, Owen Lattimore should have had some knowledge of what Russia became under communist rule. In describing in his book in some detail Wallace’s visit to the Gulag camps area in Kolyma and the role of Professor Lattimore as his chief advisor, Tim Tzouliadis observed, “Unlike the remorseful Wallace, Owen Lattimore never apologized for his portrayal of their visit to Kolyma.”13

Instead, he attacked the veracity of Elinor Lipper’s account, accusing her of being a McCarthyite pawn.14

Lattimore never said that Elinor Lipper had lied in her book, but in a patronizing manner, he tried to cast doubt on her credibility by suggesting that American conservatives had manipulated her to attack people like him. There is no evidence to support his claim. Lipper was closely associated with liberal causes, including actions supporting political prisoners and refugees.

Tzouliadis observed in The Forsaken that Lipper’s description of Wallace’s visit to Kolyma “inflicted the very worst damage upon his reputation.”15 But Lipper had nothing to do with Senator McCarthy later accusing Owen Lattimore of being a Soviet agent—an unsupported charge based on hearsay. It is doubtful that Lattimore was ever recruited as a Soviet spy. He was, however, one of many helpful Soviet agents of influence in the United States and abroad, as can be seen in his articles and through his work at the Office of War Information and the Voice of America.

In his 1951 New York Times review of Lipper’s memoir, Harry Schwartz wrote about Henry Wallace and Owen Lattimore but did not identify Lattimore as a former Office of War Information official in the Roosevelt administration. He did not identify Henry Wallace as a former U.S. Vice President under FDR. He may have assumed that, in Wallace’s case, it was not necessary since he was a well-known politician. On the other hand, Owen Lattimore was a lesser-known academic and former U.S. government official.

Schwartz also did not mention the link between Lattimore’s position in the Office of War Information and the Voice of America. It is unclear whether he knew that VOA had operated within OWI during World War II and often broadcast pro-Soviet propaganda. But he emphasized Elinor Lipper’s rebuke of Soviet disinformation in Wallace’s and Lattimore’s published reports from their 1944 trip to Kolyma.

Lipper was not an eyewitness to the visit since she was imprisoned away from the area visited by Wallace, but as a nurse, she had been told by other prisoners about the preparations for it made by the Soviet NKVD. Her account of the American delegation’s stay in Kolyma was similar to what Thomas Sgovio, a young Italian-American artist and ex-Communist who, after his arrest in 1938, spent ten years in the Gulag mining for gold and another five years in Siberia, wrote in his memoir, Dear America! Why I Turned Against Communism, published in 1979. He subtitled his book, The Odyssey of An American Youth Who Miraculously Survived the Harsh Labor Camps of the Soviet Gulag. Only after returning to the United States in 1963 did Sgovio learn that one of the men in Wallace’s party was Professor Owen Lattimore, “a representative of the United States War Information Bureau (sic)”16 Sgovio wrote:

Before his death, Mr. Wallace admitted he had been naive and gullible. Lattimore has never admitted he was duped. I shall leave it to the American people to judge the Professor.17

The New York Times book reviewer wrote in 1951 that while Lipper’s account was not the first one published in the West about “the semi-starvation, inhumanity, moral corruption, and high death rates” in the Soviet forced labor camps, she focused her attention on the suffering of women prisoners, “much more than do similar volumes by males.”18

Like Vladimir Petrov earlier, Elinor Lipper raises the question of the great disparity between actual conditions in the Kolyma gold area and the reports on these conditions submitted to the American people by Henry Wallace [U.S. Vice President in President Roosevelt’s administration] and Owen Lattimore after their visit in 1944.19

In his review for the New York Times, which he titled “A Witness from Kolyma,” Schwartz noted that Lipper debunked as entirely false Wallace’s and Lattimore’s descriptions of Soviet secret police NKVD officials in charge of the camps as “the artistic and sensitive souls.” She shows them in her book as “monstrous and heartless slave drivers.”20

During World War II, the Office of War Information included the “Voice of America” broadcasting operations. Owen Latimore was responsible for VOA and other information programs targeting China and other Asian countries. Another Office of War Information U.S. government employee in 1943 was VOA’s chief English-language news writer and editor, Howard Fast, who resigned from VOA under pressure in 1944. In 1953, Fast, a best-selling writer of historical novels who remained a communist activist until 1956 and worked for the Party’s Daily Worker newspaper, received the Stalin Peace Prize.21 Fast’s boss and the program director in charge of the Voice of America in 1942-1943 was journalist Joseph F. Barnes, also a Soviet sympathizer.

Henry Wallace, whom FDR replaced in the 1944 presidential election with Harry Truman as his running-mate, thanked Lattimore and Barnes for helping him write his book, Soviet Asia Mission: 12,000 Air Miles Through The New Siberia and China. Published in 1946, it repeated the same Soviet propaganda lies about the Kolyma gold mines included in Owen Lattimore’s 1944 National Geographic Magazine article.

“The Kolyma gold miners are big, husky young men, who came out to the Far East from European Russia,” Wallace wrote in his 1946 Soviet Asia Mission book, informing Americans that they all had volunteered for their difficult job, then after Germany’s attack on the Soviet Union volunteered to join the Red Army to fight the Nazis but were asked by the Soviet government to continue mining gold and other minerals needed for the war effort.22 He thanked Joseph Barnes for “reading the text and offering editorial suggestions” and Owen Lattimore for “intimate observations of life in East Asia.”23 In 1946, Barnes and Lattimore were former Office of War Information/Voice of America officials. Lattimore was an academic; Barnes was a journalist and publishing house editor.

In his book, Wallace even heaped praise on the Soviet NKVD communist secret police. At that time, he was unaware they were behind the deportations, murders, and starvation of millions of people and were in charge of the Gulag slave labor camps providing workers for the Kolyma gold mines. Wallace was also unaware that NKVD officials carefully staged his entire trip and that his chief guide, Sergo Arseni Goglidze, was an NKVD colonel responsible for the Soviet Far East region and executions in the Gulag camps. Goglidze was a close associate and friend of Stalin’s NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria. Both he and Beria were executed after Stalin’s death in 1953. Wallace called Goglidze “a very fine man, very efficient, gentle and understanding with people.”24 He is quoted numerous times in Wallace’s book, almost as often as Owen Lattimore. Wallace did observe the presence of NKVD functionaries during his trip but did not grasp that they were the Soviet equivalent of the Nazi Gestapo.

In traveling through Siberia we were accompanied by “old soldiers” with blue tops on their caps. They are members of the Nkvd, which means the Peoples’ Commissariat of Internal Affairs. I became very fond of their leader, Major Mikhail Cheremisenov…25

Former U.S. government information experts and officials in charge of the Voice of America, Owen Lattimore and Joseph Barnes, obviously did not tell Wallace there was something seriously wrong with his observations about the NKVD and the Soviet Union when they read his book before its publication in 1946. As the Voice of America program managers, they misled earlier foreign audiences and helped Stalin achieve domination over Eastern Europe. But they also misled Americans and, by their advice, fatally damaged Wallace’s political career. As the first VOA chief news writer and editor, Howard Fast simply censored all information about Stalin’s atrocities by rejecting it as “anti-Soviet propaganda.” In his 1990 memoir, Being Red, he wrote, “As for myself, during all my tenure there [VOA] I refused to go into anti-Soviet or anti-Communist propaganda.”26

Fast’s patron, the future Hollywood actor John Houseman, declared later as the first Voice of America director, even though he had been merely the chief of radio production rather than the person responsible for program content, was quietly forced to resign by the strongly pro-Soviet Roosevelt administration because he hired Communists for VOA jobs, which became a political embarrassment and liability for the White House. The State Department refused to give Houseman a U.S. passport for official government travel abroad, thus forcing his resignation; many other Soviet sympathizers, including Owen Lattimore, kept their OWI and VOA positions.27 In the Voice of America under Joseph Barnes, John Houseman, Howard Fast, Owen Lattimore, Wallace Carroll, and other Soviet sympathizers, the truth about Stalin’s crimes became anti-Soviet propaganda, and Soviet propaganda lies became the truth.

OWI Director, broadcaster and journalist Elmer Davis, OWI and Voice of America executive and program manager Wallace Carroll, and OWI and VOA freelancer-volunteer Kathleen Harriman Mortimer, the daughter of FDR’s wartime ambassador in Moscow W. Averell Harriman, actively spread Soviet disinformation to protect Stalin from accusations of ordering the massacre of thousands of Polish military officers captured by the Soviets in 1939—which became known as the Katyn massacre.28 These top U.S. government information experts and journalists were all deceived by one of Stalin’s greatest propaganda lies, or, knowing the Soviet explanation for the Katyn massacre was a lie, decided to embrace it because President Roosevelt believed Stalin or chose to ignore the lie to keep the Soviet leader in the war against Germany and Japan and to get his cooperation for the post-war world order. Instead of post-war cooperation from Stalin and his successors, the United States got the Berlin Blockade, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Poland and other Central European nations got nearly five decades of communist repression and economic deprivation.

During World War II, the Office of War Information and the Voice of America covered up Stalin’s massive abuses of human rights and promoted the image of Soviet Russia as a country of social justice, racial, ethnic, and gender equality, and great economic progress. In her memoirs, Elinor Lipper refuted, one by one, Owen Lattimore’s assertions in the National Geographic Magazine (December 1944), including his comparisons of the Soviet Gulag gold mines to “a combination Hudson’s Bay Company and TVA [Tennessee Valley Authority].” Lipper wrote:

But the Hudson’s Bay Company is not run by the police nor does it make use of forced labor. Furthermore, neither the Hudson Bay Company nor the TVA shoots its workers if they refuse to go to work.29

The same comparison appears in Henry Wallace’s book published two years later, “At Magadan I met Ivan Feodorovich Nikishov, a Russian, director of Dalstroi (the Far Northern Construction Trust), which is a combination of TVA and Hudson’s Bay Company.”30

As to Owen Lattimore’s statement that Mr. Nikishov, the Soviet head of the Kolyma mines, and his wife “have a trained and sensitive interest in art and music, Elinor Lipper asked, “What would Dr. Lattimore think of a man who, having visited the Nazi camps of Dachau and Auschwitz, afterwards reported only that the SS commandant of the camp had ‘a sensitive interest in art and music’?”31

I do not know what [Mr. Wallace] saw in the rest of Soviet Asia, but in Kolyma the NKVD carried off its job with flying colors,” Elinor Lipper wrote.32

Wallace saw nothing at all of this frozen hell with its hundreds of thousands of the damned. The access roads to Magadan were lined with wooden watch towers. In honor of Wallace these towers were razed in a single night.33

Lipper observed that every prisoner owed Mr. Wallace a debt of gratitude for three successive days of being excused from work. During his visit, the prisoners were not allowed to leave the camp. This was the first and the last time the prisoners had such a holiday, Lipper wrote.

Elinor Lipper was born in 1912 in Brussels, Belgium, to an affluent German-Jewish family. Her father was a businessman who moved to Switzerland after her parents divorced. She lived in her younger years with her mother in the Hague in the Netherlands and also spent time with her father in Switzerland. She became a communist activist, first in Germany, where she studied medicine and was wanted by the Gestapo. She fled to Switzerland and married a Swiss citizen, Konrad Vetterli, to avoid being exiled after the Swiss police discovered her links to the Communist Party. It was a marriage of convenience arranged by the Party that provided her with a Swiss passport and the ability to travel internationally as a Comintern agent and courier.

In 1937, Elinor Lipper traveled to the Soviet Union, where she used the name Ruth Zander, and was arrested merely two months after her arrival. Convicted of engaging in counterrevolutionary activities, she spent most of her five-year sentence and the added years of forced exile in the Kolyma Gulag, where she worked as a nurse. Her medical training, which led to her being employed as a nurse, may have helped her to survive her imprisonment. She became pregnant at the camp and, in 1947, gave birth to a daughter, Eugenia. Through the intervention of the Swiss government, she and her daughter were released in 1948 and allowed to leave the Soviet Union.

In 1950, Elinor Lipper published a book, Eleven Years in a Soviet Prison Camp, and later went on lecture tours in the United States on behalf of the Iron Curtain Refugee Campaign of the International Rescue Committee.34 She became an advocate for refugees from communist-ruled nations who were not always welcomed with open arms in the West. In 1946 and 1947, the governments of the United States and Britain carried out forced repatriations of Soviet citizens, including some Russians who had escaped from Russia after the 1918 Bolshevik Revolution, to the Soviet Union. Many of them were sent directly to the Gulag.

The New York Times reported on November 1, 1951 that Elinor Lipper spoke in New York City at the fundraising dinner of the International Rescue Committee and said in her speech that escapees from the Soviet Union “only run into another Iron Curtain” in the West—”our indifference to them.” The article said that the International Rescue Committee was seeking funds to help these refugees and “to construct a ring of nine radio stations beamed eastward in the direction of the Iron Curtain from Istanbul to Stockholm.”35

In the authorized English translation of her book from the original German, Elf Jahre in sowjetischen Gefängissen und Lagern (Zurich, Verlag Oprecht, 1950), Lipper inserted a two-page subsection on Owen Lattimore Report from Kolyma:

If his report to the Office of War Information was in substance the same as this article [“New Road to Asia” in the National Geographic Magazine, December 1944], the Office could scarcely have profited by his work. … Instead of telling us what he has seen, he hands out unexamined Soviet propaganda.36

Under Owen Lattimore and other Soviet sympathizers who were duped by Soviet propaganda, World War II Voice of America broadcasts to China and other countries presented Stalin as a champion of democracy and progress. But Prof. Lattimore also propagandized to Americans in an article published in December 1944 in the National Geographic Magazine about his visit to the Soviet gold mines in Kolyma as a high-ranking Office of War Information official in the entourage of U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace.

Owen Lattimore on “Greenhouse Vitamins for Miners” in the Soviet Gulag

Owen Lattimore’s article may hint at what kind of pro-Soviet and pro-communist Voice of America broadcasts to China and other countries in Asia were produced when he held key executive positions at the U.S. Office of War Information. The Soviet handlers took the American delegation to the Gulag gold mines, where, before and after their visit, Stalin’s prisoners were kept under the harshest conditions, and hundreds of thousands were worked to death. For the sake of the visiting Americans, the Soviet authorities transformed the work camps shown to the delegation into Potemkin villages. Well-fed and well-dressed NKVD secret police guards, who appear in a photograph taken by Lattimore and used by National Geographic to illustrate his article, were substituted for slave laborers. The Gulag camps’ shops were filled with food and goods never before seen at the sites. Lattimore was either deliberately lying or wholly convinced this was a typical Soviet enterprise. He wrote for American readers in his National Geographic article about the concern shown by the communist authorities for the health of the Soviet workers:

Greenhouse Vitamins for Miners

We visited gold mines operated by Dalstroi in the valley of the Kolyma river… . It was interesting to find instead of sin, gin, and brawling of an old-time gold rush, extensive greenhouses growing tomatoes, cucumbers, and even melons, to make sure that the hardy miners got enough vitamins!37

The Voice of America, under the direction of such OWI officials and journalists as Owen Lattimore, Joseph F. Barnes, Wallace Carroll, John Houseman, and Elmer Davis, was deceiving not only foreign audiences. Some also misled millions of Americans at home about Soviet Russia and the Communists in China. Even though members of Congress, who were alarmed about the executive branch using government funds to propagandize to Americans, eliminated in 1943, in a bipartisan vote, almost all of OWI’s domestic propaganda budget, some of these fellow traveler-journalists were still promoting in the United States their highly deceptive views of Stalin and communism thanks to their government positions and having easy access to U.S. radio networks, newspapers, and magazines.

Owen Lattimore compared the Dalstroi (also written as Dalstroy – Far North Construction Trust) “to a combination of Hudson’s Bay Company and TVA.” 38 He wrote that the workers he saw had volunteered for war but were ordered to stay because of Russia’s need for gold.39 He described in glowing terms the head of Dalstroi, Mr. Nikishov, as a recent recipient of the Order of Hero of the Soviet Union. He added that Mr. Nikishov and his wife “have a trained and sensitive interest in art and a deep sense of civic responsibility.”40 Near the Gulag camps, where thousands of prisoners died, the American delegation was entertained by “a fine ballet group from Poltava, in the (sic) Ukraine.” Lattimore quoted one member of President Wallace’s delegation as saying, “high-grade entertainment just naturally seems to go with gold, and so does high-powered executive ability.”41 Ivan Fedorovich Nikishov was a Soviet NKVD Lieutenant General.

Elinor Lipper wrote in her memoir that NKVD officials like Nikishov “like the sound of the title ‘hero of labor,’ although their labor consists solely of dreaming up newer methods for extorting a little more work from the prisoners.”42For those Americans who were not well-informed about Soviet Russia, domestic radio broadcasts and articles by Office of War Information and Voice of America U.S. government executives, Elmer Davis, Owen Lattimore, and others, made it easier to accept or tolerate President Roosevelt’s decisions of political and territorial concessions to Stalin at the expense of the people in Eastern Europe and helped Moscow establish pro-Soviet governments in the region to rule over them for more than forty years.

Henry Wallace withdrew his support for the Soviet Union during the Korean War, possibly as a result of his meeting with Elinor Lipper. In an article written in 1952, Wallace called the Soviet Union a country “utterly evil,” a term similar to the “evil empire” that President Reagan used against Soviet Russia many years later.43 In 1952, Wallace invited Lipper to visit him at his farm near South Salem, New York, while she was traveling in the United States. The two met, and Wallace apologized to her for being misled by Soviet officials during his visit to Kolyma, near the slave labor camps, where she was a Gulag prisoner.44

Russian hospitality is proverbial, and it is not surprising that on this occasion the Russians should do everything possible to impress the Vice-President of the country which was sending them so many billions of dollars of vital necessities of many kinds. So on the whole these visits made a most favorable impression on me. But, as I now know, this impression was not the complete one. Elinor Lipper, who was a slave laborer in the Magadan area for many years, has subsequently described the great effort put forth by the Soviet authorities to pull the wool over our eyes and make Magadan into a Potemkin village for my inspection. Watch towers were torn down. Prisoners were herded away out of sight. On this basis, … a false impression. I was amazed that the Russians could do so much in such short time—as was Wendell Willkie, who had visited the same region in 1942. But unfortunately neither Willkie nor I knew the full truth. As guests we were shown only one side of the coin.45

However, even after the publication of Wallace’s article, Owen Lattimore remained unapologetic and, in a patronizing manner, accused Elinor Lipper of becoming a pawn in Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist witch hunt. He implied that the chapter about him in the American edition of her book was inserted by the publisher, Henry Regnery, without her knowledge.

Islandic historian Hannes H. Gissurarson, who conducted extensive research into Elinor Lipper’s life, disputes this claim by Lattimore.46 The first authorized English translation of her book, published in Britain in 1950 for the World Affairs Book Club, had already included the subchapter on Owen Lattimore, which also appeared later in the American edition of her book. The section on Lattimore was also included in the summary of her book in the June 1951 issue of Reader’s Digest.

After Robert Conquest’s The Great Terror was published in 1968 and reviewed by other scholars, including a review by British literary critic John Gross in The New Statesman newsmagazine, Prof. Lattimore, then with the Department of Chinese Studies of the University of Leeds, took strong exception to criticism and wrote in a letter to the Editor:

It is not mentioned that Mr. Wallace was then Vice-President of the United States, that he was on an official goodwill mission, and that he was accompanied by a suitably large party. … Is it assumed that a visit of this kind affords an ideal opportunity to snoop on one’s hosts?47

Lattimore objected to how Gross analyzed for The New Statesman what the British critic called the grotesque whitewashing of Stalin:

Perhaps the most extraordinary concerns Henry Wallace and Owen Lattimore, who actually visited Kolyma in 1944 and were given a VIP reception by the commandant, the unspeakable Nikishov, and his wife (herself an NKVD officer). Both men later published lyrical accounts of what they had seen. … Lattimore was especially struck by the Nikishovs’ ‘trained and sensitive interest in art and music’ and their ‘deep sense of civic responsibility’.48

In his letter to the Editor, Prof. Lattimore said that Conquest and Gross were trying to blame him for not writing “an intelligence report ‘exposing’ what one has not seen.” He added, “It is hard, sometimes to remember those days when the Russians were saving us all.” He ended his letter with a warning against “a possible second wave of Joe McCarthyism” reemerging in America after the 1968 U.S. presidential election should Democratic Party candidate Hubert Humphrey lose to Republican Party nominee Richard Nixon.

Robert Conquest responded to Lattimore’s letter with his own, in which he wrote that he was “not concerned with blame as such so much as with showing the nature and extent of the falsehood it is possible to get intelligent men to accept, or propagate.” He noted that when Prof. Lattimore published his article in the National Geographic Magazine, evidence about the true nature of Kolyma was already available

There were many accounts from, among others, Poles (equally our allies) released under the 1941 agreement.49

John Gross also responded to Lattimore’s letter:

My objection, to put it mildly, is that while ‘good will’ may have necessitated keeping quiet, it didn’t oblige him to publish an article in a popular magazine describing Kolyma as though it were the promised land.50

Gross also wrote that Lattimore’s “humour at the expense of Miss Lipper (who suffered for years where he was entertained for days and published the truth where he transmitted the official fake) was equally misplaced.”

In his letter, Lattimore described Elinor Lipper’s book as “honest,” as far as he could tell, and “certainly a moving one.” But he noted that while the original German edition of her book did not include his name, “but when the English translation was published in America, the Joe McCarthy hue and cry was already on, so lo and behold there was a new, interpolated passage. (I still wonder who put her up to it.)” 51

Robert Conquest responded to Lattimore’s claim that criticism of his writings smacked of McCarthyism by pointing out that “McCarthyism consisted of lying about people,” but added that it is equally “inappropriate” and “a declaration of intellectual and ethical bankruptcy—to shout ‘McCarthyism’ at criticism based on irrefutable, or at any rate, unrefuted facts.”52 Conquest added:

Lattimore was himself slandered by McCarthy. But this not give him total and lifelong immunity from censure on other points.53

There was never any firm evidence that either Owen Lattimore or Joseph Barnes was an actual Soviet intelligence agent, but there was abundant evidence that they were witting or unwitting agents of influence, helping to promote the Kremlin’s propaganda. An allegation that they might have been Soviet spies, which was based only on hearsay, was secretly provided to the FBI in 1948 and made public in 1951 by the Russian Branch of the Voice of America chief, Alexander Gregory Barmine.54 He was a former Soviet military intelligence officer with the rank of brigadier general, a Soviet diplomat, businessman, a Red Army soldier in the 1920 Polish-Soviet War, and a U.S. Army soldier in World War II, a Soviet spy, and an American spy, journalist, and writer. He had escaped the Stalinist purges by defecting from his post as chargé d’affaires in the Soviet Embassy in Athens in 1937 and lived in exile under a Soviet death sentence. He was hired in 1948 to be in charge of the VOA Russian Service.

Barmine told the McCarran U.S. Senate investigative subcommittee in 1951 that his boss in the Soviet intelligence GRU, General Berzin, had identified to him in the 1930s American journalists Joseph Fels Barnes and Owen Lattimore as “his men.” According to Barmine’s testimony, General Yan Karlovich Berzin, a Latvian Communist executed on Stalin’s orders in 1938, informed Barmine in the mid-1930s that Barnes and Lattimore could help in his intelligence work in China for the Soviet Union. Barmine also told the McCarran subcommittee that while working as an advisor for Reader’s Digest, he had convinced the editors not to publish another article by Owen Lattimore, which he described as presenting the straight communist and Soviet line “camouflaged,” as he pointed out, “in very devious ways.”55

After Barmine testified, Barnes immediately called him and General Berzin “specialists in the kind of unmitigated lying professionally engaged in by both Communists and ex-Communists.” He added that he had never been a Communist, a sympathizer with communism, or an agent for the Soviet Union.56

When General Berzin reportedly described Barnes and Lattimore to Barmine as “our men” who could be of help to him in his intelligence work in China, he might have been bragging without any factual basis or meant that these Americans could provide a journalistic cover to hide the real nature of Barmine’s GRU mission, just as Latimore’s article in the 1944 issue of National Geographic obscured slave labor in the Gulag camps, Barnes’ reporting from the Soviet Union in the 1930s minimized the Red Terror, and Howard Fast’s censorship at the Voice of America helped to protect Joseph Stalin from being seen as a brutal dictator.

At least one former VOA director seemed convinced that asking about Howard Fast’s Communist Party membership smacked of McCarthyism and that those who saw communist influence within the Office of War Information and the Voice of America were white supremacists.57 While it’s true that some of VOA’s critics were racists and segregationists, particularly among southern Democrats in the U.S. Congress, most of the congressional criticism came from moderate northern Republicans and Democrats.

Moreover, some of the earliest critics of pro-Soviet propagandists within the ranks of OWI and VOA were former Communists and communist sympathizers, including Julius Epstein; Elinor Lipper; Bertram Wolfe, who later worked in the State Department, producing VOA programs about the Soviet Katyn massacre, which VOA officials and journalists covered up; Alexander Barmine; journalist and writer Eugene Lyons, who, before his break with communism, interviewed Joseph Stalin; and Oliver Carlson, the founder of the Young Communist League of America. Some were Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe and could hardly be described as “white supremacists.” Even though they broke with communism, they remained socially progressive, and some, like Elinor Lipper, still called themselves Socialists. They were some of the best-informed and the most credible critics of the Soviet Union and Soviet propaganda in the Office of War Information and the early Voice of America programs.

Elinor Lipper was a remarkable and compassionate woman who, despite all the injustice and suffering she had experienced in the Soviet Union, never blamed the Russian people. She pointed out in the foreword to her book that they did not have the slightest chance to control their rulers.

It is easy to condemn “the Russians”—but to do so is to do the Russian people a great injustice.58

In June 1950, Elinor Lipper participated in the inaugural meeting in West Berlin of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an organization secretly funded by the CIA. Some of the most prominent participants were: American philosopher John Dewey, anti-fascist Italian novelist Ignazio Silone, French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain, former American Trotskyist who became a critic of Soviet imperialism James Burnham (the CIA secretly employed him to organize the meeting), English historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, American historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., British philosopher Bertrand Russell, Hungarian-born writer Arthur Koestler, and American playwright Tennessee Williams.

During that time, Lipper became acquainted with Russian-American composer Nicolas Nabokov, a cousin of writer Vladimir Nabokov of Lolita‘s fame. Nicolas Nabokov was greatly impressed, almost enchanted by this “extraordinarily beautiful” woman, describing her in his memoirs as having a “dark, sad, and tender eyes,” a gentle smile, soft voice, and “infinitely vulnerable warmth and a suspicious caution.”59 She told him the Berlin Congress was “silly,” and she felt exploited.60

Nicolas Nabokov had been employed earlier by the Voice of America to work on Russian-language VOA broadcasts. His boss as the first chief of the VOA Russian Service and later VOA director was State Department diplomat Charles W. Thayer. Vladimir Nabokov was apparently also considered for work with the Voice of America, but the job in the VOA Russian Service went to Nicolas, who was among Thayer’s many Russian friends. Before he became famous and rich, Vladimir complained about not getting the job he thought had been promised to him.61

VOA broadcasts in German and many other foreign languages were first launched in 1942. Strangely, VOA did not have programs in Russian before February 1947 because U.S. officials apparently had feared until some time after the war that direct broadcasting to the Soviet Union might offend Joseph Stalin. The VOA Russian-language broadcasts started by Charles Thayer in 1947 were not critical of the Soviet government. Congressional critics dismissed them as ineffective. Nabokov was not responsible for their content and had no experience working for a bureaucratic government organization. In an unpublished manuscript for his second book of memoirs, Nabokov described his brief employment with the Voice of America “as something hilariously funny, earnest in its aims, and as disappointing as sweet-sour pork in a third-class Chinese restaurant.”62 In the published version of his memoirs, Nabokov is less brutal about his brief government job, which he described as “helping Charlie Thayer, Charles Bohlen’s delightful brother-in-law, to organize, at the request of the State Department, the Voice of America to Russia.”63 He quit government service after six months, “vowing never to return.”64

Nicolas Nabokov held strongly anti-communist views, but since he had many gay friends, the FBI falsely suspected him of being a homosexual and also suspected Thayer of being gay and possibly being vulnerable to blackmail. Both Nabokov and Thayer, however, were married. Nabokov seemed genuinely fond of Thayer and did not suggest in any way that Thayer was soft on communism or Stalin, but as a State Department diplomat, he may have felt that VOA programs to Russia should not be critical of the Soviet government and should not try to expose Stalin’s many crimes, including the Katyn massacre.

After leaving his VOA job, Nicolas Nabokov became Secretary General of the CIA-supported Congress for Cultural Freedom, which helped many anti-Soviet writers and artists, including many left-leaning Western intellectuals who became disenchanted with communism. He was initially unaware that the CIA was paying his CCF salary and created and funded the entire organization.65

He wrote in his memoirs that Lipper felt exploited by people and organizations trying to make her into an “anti-Stalinist propaganda showpiece,” but she refused to go along.66

Rarely have I met a human being endowed with so much quiet courage and intelligence, so much gentleness and integrity.67

Nabokov explains in his book that Lipper belived her public role was done after she had written down her experiences in the Soviet prison camps. She wanted to provide a normal family life for her young daughter and married a doctor. Nabokov wrote that after September 1950, he never saw her again.68

Before she withdrew from public life, Elinor Lipper was a witness in a libel suit brought by French socialist writer and former Nazi concentration camps prisoner David Rousset, who was defending himself against attacks by the French communist newspaper Les Lettres Françaises, which claimed that Rousset slandered the Soviet Union by writing about the existence of forced labor camps in Russia. Rousset, who wrote books about Nazi and Soviet concentration camps, won the French court case in 1951.

Another witness in the trial initiated by Rousset was a former World War II prisoner of war in the Soviet Union, Polish military reserve officer, writer, and artist Józef Czapski, whose program about the Katyn massacre for the Voice of America Polish Service was censored by VOA management in 1950.69 Czapski and Elinor Lipper became acquainted during the Rousset case trial, but I found no evidence of any correspondence between them. Czapski also attended the Berlin Congress for Cultural Freedom meeting, at which Lipper was present.

While promoting her book in the United States, Lipper met in November 1951 the former prime minister of the World War II Polish government-in-exile in London, Stanisław Mikołajczyk, who, during the war, complained to the Roosevelt administration about the pro-Soviet propaganda in the Office of War Information’s Voice of America Polish-language broadcasts.70 According to one U.S. Foreign Service diplomat, the Voice of America reviewed Mikołajczyk’s book published after the war but censored information from his book about the Soviet responsibility for the Katyn massacre.71

The same diplomat, Chester H. Opal, wrote in a secret memo in January 1951 that the first chief of VOA’s Russian Service and later VOA director, Charles W. Thayer, was not convinced that the Russian NKVD secret police murdered thousands of Polish officers in Katyn.72

Among more than a dozen American and other Western journalists in Moscow whom the Soviet regime took to Katyn in January 1944, the only one who chose not to report anything for African-American newspapers rather than repeat Soviet lies was Homer Smith.73 Most of these elite white colleagues who were with Homer Smith reported for American, British, Canadian, and other Western media what the Soviet experts had told them, even though most realized they were being deceived. The U.S. ambassador’s daughter, OWI volunteer employee, and Thayer’s friend Kathleen Harriman concluded that the Germans had carried out the murders. Not a single Western journalist reported that the Soviet NKVD was the most likely perpetrator of this war crime.

Among more than a dozen American and other Western journalists in Moscow whom the Soviet regime took to Katyn in January 1944, the only one who chose not to report anything for African-American newspapers rather than repeat Soviet lies was Homer Smith.73 Most of these elite white colleagues who were with Homer Smith reported for American, British, Canadian, and other Western media what the Soviet experts had told them, even though most realized they were being deceived. The U.S. ambassador’s daughter, OWI volunteer employee, and Thayer’s friend Kathleen Harriman concluded that the Germans had carried out the murders. Not a single Western journalist reported that the Soviet NKVD was the most likely perpetrator of this war crime.

In his Black Man in Red Russia memoir, published in 1964 after his return to the United States, Smith wrote:

It has always been my opinion that American and British wire services or large newspapers which maintained bureaus in Russia were willy-nilly rendering a valuable, free service to the Soviet Government. These agencies and newspapers were devoting large sums of money toward spreading before foreign readers only what the Soviet authorities wanted them to read.74

Smith explained that unless the Soviet censors approved reports submitted to be cabled out of the Soviet Union, nothing could be sent abroad. Consequently, Western reporters “performed careful pre-censoring of their stories.”75

The journalist at the Office of War Information in New York during World War II, who realized that the Soviet regime was behind the Katyn murders, was OWI’s German editor Julius Epstein, an Austrian-Jewish refugee in the United States who, in his youth, had joined the Communist Party in Germany but quickly resigned and became of a critic of Stalinist Russia. After being laid off by OWI in 1945, he exposed the Voice of America’s censorship of the Katyn story and was attacked by VOA director, State Department diplomat Foy D. Kohler, who called him a “disappointed job seeker” and “not best type…of new American citizen.”76 In The Gulag Archipelago, Soviet dissident writer and Nobel Prize winner Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, whom the Voice of America management censored in the 1970s to prevent complications in the U.S. policy of detente with the Soviet Union, praised Julius Epstein’s investigative reporting—not in connection with VOA, but in Epstein’s book Operation Keelhaul (1973).77 In his book, Epstein revealed another shameful U.S. government secret—the forcible handing over to Stalin of hundreds of thousands of Soviet refugees, many of whom were innocent of collaborating with the Germans and did not want to go back to Russia.

Elinor Lipper was warmly received in the United States in the early 1950s but not among some pro-Soviet American intellectuals and Hollywood actors. During her lecture tour in the United States, she met some of them at actress Bette Davis’ Malibu home. According to Marvin Liebman, an American conservative activist and, later in life, a gay rights advocate, almost no one at the Hollywood gathering believed what she had said about Soviet Gulag labor camps was true.

The Hollywood guests sat on the floor and listened to this woman talk about the horrors of her life. Yet, almost to a person, they disbelieved her. How could she have been in a slave labor camp when her complexion was so good and she was so pretty?78

Liebman wrote that he had changed his early positive view of Soviet Russia and Soviet communism after meeting Lipper in 1951.

Her story overwhelmed me. I felt totally betrayed. What was worse, because I had believed in the Soviet Union, I felt personally responsible for what had happened to her.79

In her book, Lipper describes the sexual exploitation of women prisoners in the Soviet Gulag, rapes, torture, starvation, and countless other horrific crimes against men, women, and children. Before meeting Lipper, Liebman told his friend, who had suggested that he help organize fund-raising for her in San Francisco and Los Angeles on behalf of the International Rescue Committee, that she was “obviously a fraud” because he was convinced that there were no slave labor camps in the USSR.80 But his friend insisted that he should meet her and talk to her.

Liebman’s meeting with Lipper at the Algonquin Hotel lobby in New York had a profound impact on his life.81 He arranged for Lipper, at her request, to meet former Vice President Wallace in January 1952. According to Liebman, when Lipper told Wallace how he had been deceived during his tour of Siberia, his face paled, and he kept saying, “I didn’t know—please believe me—I just didn’t know.”82

Liebman also wrote that he sympathized with Owen Lattimore, who was the father of one of his friends, when he came under attack by Senator Joseph McCarthy. But when Liebman discovered what Lattimore had said in Siberia, he “felt betrayed by him, too.”83

In one of many ironies of the Voice of America’s history, VOA’s parent federal agency since 1953, the United States Information Agency (USIA), apparently promoted in the 1950s the translation into foreign languages and distribution of Elinor Lipper’s book about Soviet Gulag slave labor camps, while earlier, the U.S. government’s information agency during World War II, the Office of War Information and the wartime Voice of America, helped to cover up Soviet human rights abuses, with some of the coverup by VOA continuing until 1951. According to Henry Regnery, the American publisher of Lipper’s memoirs, the United States Information Agency distributed over 300,000 copies of Eleven Years in Soviet Camps in sixteen languages.84

Henry Regnery described Elinor Lipper as “a trim, bright, and attractive woman.” He wrote that she could impress any audience with her sincerity and conviction “whether she spoke before the executive board of the AFL-CIO, to an American Legion auxiliary, or at a New York press conference.”85 Regnery also noted that Henry Wallace, whom he called a “naive man,” personally expressed his regret to Lipper about what he had written after his 1944 trip to Soviet Siberia.

“But there is no evidence,” Regnery added, “that Owen Lattimore, who was not a naive man, ever expressed regret for his part in this inexcusable case of deception.”86 The management of the Voice of America and its current parent federal agency, the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM), likewise has never apologized for its part in misleading foreign audiences and Americans about Soviet Russia and Stalin during World War II, and even for some time after the war.

Most of the Office of War Information and the Voice of America officials who were duped by Soviet propaganda were New Deal Roosevelt Democrats, but many of the critics who first exposed communist influence within VOA were also liberals, and some were former Communists or former Soviet sympathizers, including Elinor Lipper, Julius Epstein, Alexander Barmine, Bertram Wolfe, Eugene Lyons, and James Burnham. The Democratic Truman administration forced many of the pro-Soviet bureaucrats and VOA broadcasters to leave and hired journalists who were refugees from communism in Eastern Europe, including the Polish anti-Nazi underground resistance fighter Zofia Korbońska.87 The Truman administration also oversaw the establishment of Radio Free Europe (RFE), the radio station initially secretly funded and managed by the CIA. Unlike VOA, RFE and similarly-established Radio Liberty never censored reports about the Katyn massacre and never banned Solzhenitsyn.

The Republican Nixon and Ford administrations banned the VOA Russian Service from interviewing Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, albeit not out of ideological sympathy for communism or Soviet Russia as in the early years, but in order not to upset the policy of detente with Moscow.88 However, the anti-communist refugee journalists, still treated as second-class employees by the American management and having their work censored much of the time until the beginning of the Reagan administration, finally managed to reverse most of the damage done by the early Soviet sympathizers and contributed to the winning of the Cold War. In today’s America, unlike in the earlier period, those most likely to be deceived by Russian propaganda of President Vladimir Putin are extreme right-wing Americans in the private media and in the radical right-wing of the Republican Party.

In 1951, Lipper married Just Robert Català, a specialist in tropical diseases. She went with her husband to Madagascar and was no longer politically active. She later returned to Switzerland and worked as a writer and translator. Elinor Lipper-Català died on October 9, 2008.89

NOTES:

- Henry A. Wallace, Soviet Asia Mission: 12,000 Air Miles Through The New Siberia and China (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1946), p. 17.

- Ibid., p. 156.

- Ibid., p. 197.

- Tim Tzouliadis, The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin’s Russia (New York: Penguin Books, 2008), pp. 104-105.

- Ibid., pp. 30-37.

- Ibid., p. 50.

- Ibid., pp. 1-11.

- Ibid., pp. 98-99.

- Ibid., p. 99.

- Ibid. p. 269.

- Robert Robinson and Jonathan Slevin, Black on Red: My 44 Years Inside the Soviet Union: An Autobiography (Washington, D.C: Acropolis Books, 1988), p. 13. Robinson may not have been the only one who was not arrested. African-American journalist Homer Smith apparently also accepted Soviet citizenship in 1938 so that his Russian wife “would not be sent to Siberia.” This information was included in the JET magazine article, “Newsman Who Became Russian, Seeks Entry to U.S.,” November 28, 1957, p. 45.

- Ibid., p. 14. Robinson was angry with Homer Smith, whom he had asked in 1935 to accompany him to see U.S. Ambassador William Bullitt about having his American passport extended. Smith, who at that time apparently still believed in communism, offended Bullitt by calling him “comrade” (p. 109) Robinson’s request was denied.

- Tim Tzouliadis, The Forsaken, p. 282.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 281.

- Thomas Sgovio, Dear America! Why I Turned Against Communism (Thomas Sgovio and Sgovio Family, 1979), pp. 329-330.

- Ibid. p. 331.

- Harry Schwartz, “A Witness From Kolyma,” The New York Times, March 25, 1951, p. 169, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1951/03/25/87196761.html?pageNumber=169.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ted Lipien, “Created 70 Years Ago, Stalin Peace Prize Went in 1953 to Former Voice of America Chief News Writer Howard Fast,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), December 21, 2019, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/created-70-years-ago-today-stalin-peace-prize-went-in-1953-to-former-voice-of-america-chief-news-writer-howard-fast/.

- Henry A. Wallace, Soviet Asia Mission, p. 35.

- Henry A. Wallace, Soviet Asia Mission, “Author’s Note.”

- Ibid., p. 82

- Ibid., p. 84.

- Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), p. 23.

- Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director Was a Pro-Soviet Communist Sympathizer, State Dept. Warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), May 5, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/.

- Wallace Carroll, Persuade or Perish (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1948), pp. 149-152. Also, Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Freelancer Who Promoted Stalin’s Propaganda Lie on Katyn Massacre, Cold War Radio Museum,” April 25, 2023, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-freelancer-who-promoted-stalins-propaganda-lie-on-katyn-massacre/.

- Elinor Lipper, Eleven Years in Soviet Prison Camps (London: The World Affairs Book Club, 1950), p. 115.

- Henry A. Wallace, Soviet Asia Mission, p. 33.

- Elinor Lipper, Eleven Years in Soviet Prison Camps, p. 117.

- Ibid., p. 266.

- Ibid., p. 267.

- José Vergara, “11 Years in Soviet Prison Camps,” Crime or Punishment: Russian Narratives of Incarceration, accessed June 19, 2023, https://crimeorpunishment.jvergara.digital.brynmawr.edu/crime-or-punishment/11-years-in-soviet-prison-camps.

- The New York Times, “Escape Held Futile: Those Who Flee Russia Are Said to Face Second Iron Curtain,” November 1, 1951, p. 12, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1951/11/01/issue.html.

- Lipper, Eleven Years in Soviet Prison Camps, p. 114.

- Owen Lattimore, “New Road to Asia,” National Geographic, December 1944, p. 567.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 642.

- Ibid., p. 657.

- Ibid.

- Lipper, Eleven Years in Soviet Prison Camps, p. 216.

- Henry A. Wallace “Where I Was Wrong”, The Week Magazine, September 7, 1952, https://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2013/02/henry-a-wallace-1952-on-the-ruthless-nature-of-communism-cold-war-era-god-that-failed-weblogging.html.

- Hannes Holmsteinn Gissurarson, Totalitarianism in Europe – Three Case Studies, “The Survivor – Elinor Lipper: A Brief Note on a Little-Known Episode of the Cold War,” (Reykjavik: ACRE, 2018), https://rafhladan.is/bitstream/handle/10802/23125/ACRE-Totalitarism-preview%28low-res%29.pdf?sequence=1 .

- Ibid.

- Gissurarson, Totalitarianism in Europe – Three Case Studies.

- Owen Lattimore, “Letters to the Editor,” New Statesman, October 11, 1968, p. 461.

- John Gross, “The Years of the Purges,” New Statesman, September 27, 1968, pp. 397-398.

- Robert Conquest, “Letters to The Editor,” The New Statesman, October 18, 1968, p. 496.

- John Gross, “Letters to The Editor,” The New Statesman, October 18, 1968, p. 496.

- Owen Lattimore, “Letters to the Editor,” The New Statesman, October 11, 1968, p. 461.

- Robert Conquest, “Letters to the Editor,” The New Statesman, October 18, 1968, p. 496.

- Ibid.

- Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Russian Branch Chief Alexander Barmine Was An Ex-Soviet General and Ex-Spy Who Testified Before Senator McCarthy,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), April 17, 2023, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-russian-branch-chief-alexander-barmine-was-an-ex-soviet-general-and-ex-spy-who-testified-before-senator-mccarthy/.

- United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on the Judiciary. Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws., United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on the Judiciary. Subcommittee Investigating the Institute of Pacific Relations. (1951-1952). Institute of Pacific Relations: Hearings before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee To Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws, Subcommittee Investigating the Institute of Pacific Relations, Eighty-Second Congress, First Session, Eighty-Second Congress, Second Session. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., p. 215, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d02120505q?urlappend=%3Bseq=225%3Bownerid=13510798903345995-229.

- William S. White, “Lattimore and Barnes Linked to Soviet Spies But Deny It,” The New York Times, July 31, 1953, p. 1, and p. 7, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1951/08/01/88438625.html?pageNumber=1.

- Ted Lipien, “A Stalin Peace Prize Laureate Still Waiting for Acknowledgement of His Soviet Agent of Influence Role at Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum, November 7, 2022, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/a-stalin-peace-prize-laureate-still-waiting-for-acknowledgement-of-his-soviet-agent-of-influence-role-at-voice-of-america/.

- Lipper, Eleven Years in Soviet Prison Camps, p. v.

- Nicolas Nabokov, Bagázh: Memoirs of a Russian Cosmopolitan, 1st ed (New York: Atheneum, 1975), p. 241. Also quoted in Vincent Giroud, Nicolas Nabokov: A Life in Freedom and Music (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 231.

- Vincent Giroud, Nicolas Nabokov, p. 234.

- Ibid., p. 202.

- Ibid., p. 203.

- Nicolas Nabokov, Bagázh, pp. 172-173.

- Ibid., pp. 232-234.

- Ibid. p. 243.

- Ibid., 241.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ted Lipien, “Pro-Stalin Voice of America Propaganda Revealed in 1984 VOA Interview with Józef Czapski,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), September 4, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/stalins-american-voice/.

- Gissurarson, Totalitarianism in Europe – Three Case Studies.

- Ted Lipien, “Secret Memos on How Voice of America Was Duped by Soviet Propaganda on Katyn Massacre,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), May 2, 2021, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/secret-memos-on-how-voice-of-america-was-duped-by-soviet-propaganda-on-katyn-massacre/.

- Ibid.

- Ted Lipien, “Black History Hero Homer Smith Fought Racism at Home and Soviet Propaganda Abroad,” Washington Examiner, February 28, 2022, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/restoring-america/patriotism-unity/black-history-hero-homer-smith-fought-racism-at-home-and-soviet-propaganda-abroad.

- Homer Smith, Black Man in Red Russia, (Chicago: Johnson Publishing Company, 1964), p. 90.

- Ibid.

- ”VOA CRITICS” Memorandum, Voice of America Historical Files 1946-1953 Reports-Psychologial Operations POC THRU Katyn Forest Massacres, RG59-Department of State-Entry#P315, National Archives at College Park, MD.

- Aleksandr Isaevich Solzhenit︠s︡yn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, 1st ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), p. 85.

- Marvin Liebman, Coming Out Conservative: An Autobiography (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1992), p. 88.

- Ibid., p. 87. Also quoted in Gissurarson, Totalitarianism in Europe – Three Case Studies.

- Ibid., p. 85.

- Ibid., p. 87.

- Ibid., p. 88.

- Ibid.

- Henry Regnery, Memoirs of A Dissident Publisher (Chicago: Regnery Books, 1985), p. 106.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ted Lipien, “LIPIEN: Remembering a Polish-American Patriot,” The Washington Times, accessed May 13, 2023, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2010/sep/1/remembering-a-polish-american-patriot/.

- Ted Lipien, “SOLZHENITSYN Target of KGB Propaganda and Censorship by Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), November 7, 2017, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/solzhenitsyn-target-of-kgb-propaganda-and-censorship-by-voice-of-america/.

- Gissurarson, Totalitarianism in Europe – Three Case Studies.