By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

for the Office of War Information (OWI), the parent agency of the Voice of America (VOA).

Kathleen Harriman Mortimer was an American journalist working during World War II in Great Britain and Russia as an occasional freelance news reporter for the U.S. government. She was also the daughter of the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union—young, attractive, rich, and made famous in the Soviet press. Toward the end of her stay in Russia, communist dictator Joseph Stalin gave her a gift—a horse who had served at the battle of Stalingrad— in an unusual gesture of gratitude to an American. He also gave a horse to her father, W. Averell Harriman, the fourth richest man in America in 1946, according to a British illustrated magazine article about Kathleen Harriman, as she prepared to be the embassy hostess at her father’s next post in London.1 In January 1944, as a journalist and her father’s representative when he was U.S. ambassador in Moscow, she helped to save Stalin’s reputation in a secret report she wrote for the State Department in Washington by misinterpreting the evidence of one of his most cruel atrocities, which became known as the Katyn Forest massacre. In a victory for Soviet propaganda, she exonerated him of the brutal murders of thousands of Polish military officers who became prisoners of war in Russian captivity after the Soviet Union attacked Poland in September 1939 in alliance with Hitler’s Germany. Stalin was grateful to the Harrimans for literally helping him get away with murder, but his gift of the two horses may have also been his twisted way of mocking the two Americans for allowing themselves to be easily deceived or for going along with his deception, knowing that he was guilty of the crime.

Cruel mockery was Stalin’s way of dealing with people whom he victimized. He had given earlier two horses and an old American Packard automobile to Polish General Władysław Anders, who was interrogated and tortured in the Lubyanka prison in Moscow.2 Anders was released after the German attack on the Soviet Union and needed officers for the Polish Army being formed in Russia to fight Germany. Stalin lied to Anders, telling him that the missing Polish prisoners, whom he knew the Soviet secret police NKVD had already executed, may have escaped to Manchuria. Suspecting the officers were dead and knowing he could not trust Stalin, Anders took his troops with tens of thousands of Polish civilian refugees from the Soviet Union to Iran. His army, the Polish II Corps, later fought against the Germans alongside British and American troops in Italy. Most of the Polish officers and soldiers in Anders’ army had their homes in the territories taken over by the Soviet Union in 1939 under the Hitler-Stalin Pact and again at the end of World War II as a result of the Yalta Conference. After the war, the vast majority of Polish soldiers in the West and their families chose not to return to Poland, governed by the Moscow-backed communist regime, and became refugees. Averell Harriman had a long career as an elder statesman. In 1947, Kathleen Harriman married Stanley G. Mortimer Jr., a member of the Four Hundred most prominent New York families.

Three years after she wrote her report about the Katyn massacre with her false conclusion that it was a German rather than a Russian war crime and two years after serving at her father’s request as a housekeeper of the Yalta Conference, Kathleen Harriman was back in the United States, working as a volunteer for the U.S. government to help launch Voice of America (VOA) Russian-language radio broadcasts. She was not responsible for the content of these programs, which went on air for the first time in February 1947. It was the job of a State Department diplomat put in charge of the Russian Service, Charles W. Thayer, who later became VOA director. It was Thayer who recruited her as a volunteer employee in violation of government regulations.

In agreeing to do work for the Voice of America on Russian programs, Kathleen Harriman did not have to worry about offending Stalin. It was not Thayer’s intention to cause any offense to the Soviet leader. He was not convinced that Katyn was Stalin’s crime, and Kathleen Harriman had reported earlier that it was not. As a popular figure with Stalin and the Russians, Kathleen Harriman was a perfect choice to help the head of the newly established Voice of America Russian Service to start the broadcasts to Russia. Their purpose was not to point out Soviet human rights abuses or to criticize communist leaders. It was to show that the United States was a friendly country wanting better relations with the Soviet Union.

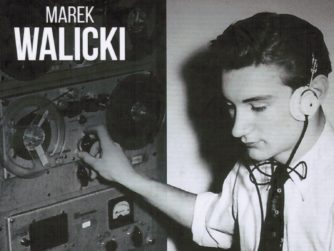

As one of the early VOA Russian broadcasters, Helen Yakobson, recalled, in the first broadcasts to Russia, “No direct criticism or attacks on the Soviet system were permitted.” She further noted, “After all, they had only recently been our allies.”3 A researcher, Edward Carleton Helwick, Jr., who had worked for the Voice of America, observed that the new program was not regarded in the United States as a great success against Soviet propaganda.

It was evident from newspaper accounts that the broadcast in America, at least, was received with something less than enthusiasm. Typical of the reactions was the New York World Telegraph headline, “Russians Restrain Joy Over U.S. Broadcast.”4

According to an Associated Press (AP) report several days before the launch of VOA Russian-language programs, all staff broadcasters were “carefully screened to eliminate any with either Communist or anti-Soviet feelings.” It was a clear sign to the Kremlin that the State Department and the Voice of America were not planning to confront Russia over human rights abuses. AP also reported that the selection of Russian broadcasters was ”understood to have been a major concern of Assistant Secretary of State William Benton.” All staff members were U.S. citizens.5 Helwick’s description of the first broadcast was less than flattering:

The first program [Voice of America Russian broadcast in February 1947], a widely publicized event, had consisted of a twenty minutes of straight news; a twelve minute lecture on the United States form of government, which said, among other things, that the U.S. had lost its fear of the “so-called despotism of the central government”; an interlude of cowboy tunes, including “The Old Chisholm Trail,” the refrain of which, “coma ti yi soupy, happy yay, happy ya, come ti yi soupy happy yay,” Time observed, “probably sounded like static to Russian ears”; a talk on a new cure for hay fever, revealing that the U.S. had 5 million sufferers; and details of a new method of exploring the Milky Way.6

Former U.S. Ambassador to Poland, Arthur Bliss Lane, who resigned from his post in 1947 in protest against the U.S. policy of ignoring Soviet violations of the Yalta Conference agreements on free elections and democracy, dismissed Voice of America programming policy as inappropriate to what was happening in Eastern Europe and in Stalinist Russia. He wrote in his book, I Saw Poland Betrayed, published in 1948:

As for radio broadcasts beamed to Poland as the “Voice of America,” my opinion of their value differed radically from that of the authors of the program in the Department of State. …I felt that the Department’s policy to tell the people in Eastern Europe what a wonderful democratic life we in the United States enjoy showed its complete lack of appreciation of their psychology. And, especially in Poland, which had suffered through six years of Nazi domination, it was indeed tactless, to say the least, to remind the Poles that we had democracy, which they also might again be enjoying, had we not acquiesced in their being sold down the river at Teheran and Yalta.7

Ambassador Lane added, “If appropriate material is used which will bring hope and cheer, instead of intensifying despair, there is much of a constructive nature that we can do. But the wisdom of statesmanship, not that of salesmanship, is a requisite.”8 His comments could also apply to the first Voice of America programs to Soviet Russia. Even four years later, Congressman John V. Beamer (Republican – Indiana) said on the floor of the House of Representatives on July 24, 1951, “Day by day, the evidence is mounting that the Voice of America, as now managed and operated, is about as hard-hitting as a creampuff. Improvements certainly are necessary.” He revealed that VOA had practically no audience in pre-Castro Cuba.9 By then, however, the Truman administration had already started changing VOA’s staff and reforming programs to make them more hard-hitting against communism.

Kathleen Harriman played only a small part in launching the Voice of America Russian broadcasts in 1947. Still, there was important symbolism in her involvement as the daughter of a former U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union and as a journalist who had saved Stalin from being confronted with a war crime that could have cost Moscow its hegemony over Eastern Europe. Yet, this historical controversy, her fascinating life, her connection to Russia, the U.S. government’s wartime propaganda, and the Voice of America remain unknown to most past and current VOA officials, editors, and reporters. She has been excluded from VOA’s official history because apologists for the taxpayer-funded broadcaster want to present the U.S. government’s media entity as having an unbroken record of telling the truth regardless of whether the news is good or bad.10 Kathleen Harriman accepted a blatant Soviet propaganda lie as the truth. Because she was mixed up in the Katyn controversy, although her mistake was not in a Voice of America broadcast, to protect the institution from public embarrassment, her name never appeared in VOA’s promotional materials, on PR websites, or social media pages

Kathleen Harriman’s report from Katyn had undeniably profound implications and, therefore, it could have provided a valuable lesson to new generations of Voice of America journalists if the management chose to discuss it. But journalists, in general, are not known for readily admitting their errors, failures, biases, and conflicts of interest. They have the skills to be better than most in hiding or excusing poor judgment. Government officials and employees who are also VOA journalists have even more reasons and resources to obscure the truth if they make a particularly tragic error. To protect their reputation and jobs and assure continued and increasing public funding for their programs, they do not hesitate to present their individual and collective failures in the entire period from World War II to Afghanistan as an unending string of Voice of America’s successes. There has been for many decades an unwritten institutional ban on discussing events and individuals who do not meet the criteria of “good news” about VOA. Kathleen Harriman is one of many persons who have disappeared from the official history of the Voice of America.

In 1952, Kathleen Harriman Mortimer was called to testify before a bipartisan congressional committee investigating the Katyn massacre, which also examined and sharply criticized VOA’s news reporting about this and other communist atrocities and human rights violations. In her testimony, she admitted that in 1944 she wrongly had blamed the Germans for the Katyn massacre. This admission may explain why the station’s management and journalists, with perhaps one exception in 1959, never mentioned her name in promotional materials, articles, and books. Charles Thayer wrote about employing her as a VOA Russian Service volunteer in 1947, but he did comment on her mistake in reporting from Katyn for the State Department or on her later congressional testimony. The Voice of America has ignored her, even though she had played a part in VOA’s early history for a brief period as one of the institution’s first female American-born freelance radio producers or broadcasters. While her employment as a volunteer in the VOA Russian Service has been documented, it is unclear what kind of work she had performed. Since her knowledge of Russian was limited, it could not have been anything substantial, but it could have had symbolic significance.

Most Americans know nothing or very little about Kathleen Harriman. During the war years, she did volunteer work as a journalist in the federal government agency—the United States Office of War Information (OWI) that managed VOA until 1945. Some may have learned who she was by reading a recently published book by Catherine Grace Katz, The Daughters of Yalta: The Churchills, Roosevelts, and Harrimans: A Story of Love and War. Katz’s book paints a highly idealized picture of the young American journalist from a wealthy and privileged family. It was translated into Polish and published in Poland (Córki Jałty: Sarah Churchill, Anna Roosevelt, Kathleen Harriman i kulisy wielkiej polityki). However, Kathleen Harriman’s witting or unwitting help in hiding Stalin’s responsibility for the murders of thousands of Polish military officers has not endeared her to the Poles. They may know more about her than most Americans, but even there she is not widely remembered, except among historians and those who have read books about the Katyn massacre.

Most of the scorn in Poland is reserved for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the results of the “Big Three” Yalta Conference (February 4-11, 1945), where Kathleen Harriman had housekeeping duties, but played no other role. Her father, however, was one of Roosevelt’s key advisors at Yalta. Poland’s borders were changed due to decisions made in Yalta and later confirmed at the Potsdam Conference (July 17 to August 2, 1945), with the Soviet Union taking over nearly half of the country’s pre-war territory in the east without the Poles’ knowledge or approval. While the Poles were partly compensated with some of the territories in the West, which before the war had belonged to Germany. Poland’s wartime government-in-exile in London was not consulted or even informed by President Roosevelt about the changes to their country’s borders he made with Stalin and Churchill at Yalta. As a result of the Yalta agreements, those Poles not already in the West and unable to flee were condemned to live under Soviet domination in socialist poverty without fundamental human rights for several decades.

Poland was not the only nation affected by Yalta. The U.S. President’s decisions, which incorporated his secret assurances about Poland’s future borders given to Stalin already at the Teheran Summit (November 28 to December 1, 1943), made other East-Central Europeans lose their freedom. A Soviet spy, Flora Don Wovschin, employed at the Office of War Information and the Voice of America library and research unit in New York, prepared a report justifying the move of Russia’s borders to the west along the Curzon Line per Stalin’s wishes.11 At Teheran and Yalta, President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill were not concerned whether the Ukrainians and the Belorussians, who had majorities in parts of pre-war eastern Poland, wanted their own independent and democratic nations. American and British leaders, in effect, allowed Stalin to keep Lithuania and the other Baltic countries, Latvia and Estonia, which, between the wars, during and after World War II, were recognized by the United States as independent states.

While Kathleen Harriman was helping to launch Voice of America broadcasts in Russian, VOA Polish programs initially supported the pro-Moscow communist-dominated government in Poland. At the same time, anti-communist Poles were being arrested and tortured and, in at least tens of thousands of cases, executed by the UB communist secret police. Other anti-communist Poles who had fought the Nazis were sent from Poland to the Gulag prison camps in Siberia, some for the second time. Atrocities similar to those in Poland occurred in all other nations dominated by Soviet Russia. Several former Office of War Information employees and Voice of America journalists left the United States after the war to work for the communist regime in Warsaw as its anti-American and pro-Soviet propagandists. The former VOA Czechoslovak Service chief, Adolf Hoffmeister, returned to Prague, joined the Communist Party, and became the Czechoslovak regime’s ambassador to France.12

For millions of people in East-Central Europe, the end of World War II was a defeat in victory, which was the title of memoirs of Poland’s wartime ambassador in Washington Jan Ciechanowski.13 Stalin and the communist regime in Poland quickly violated the weak conditions with regard to free elections agreed to in Yalta by Roosevelt and Churchill without any provisions for enforcement. The Poles understood that the loss of their country’s independence was mainly Stalin’s fault, but they also blamed the Western leaders. It is not surprising that for those Poles who knew about her, Kathleen Harriman has developed a somewhat infamous reputation in their country’s World War II and post-war history as one of the Americans who had betrayed Poland and handed it over to Stalin. Although her role was accidental, it was significant in its impact. However, she had nothing to do with the critical decisions of the American government made without the full knowledge of the American people. They were made by President Roosevelt and his advisors, including Ambassador Harriman.

Still, the Poles who knew of her earlier role during the Soviet investigation of the Katyn murders were dismayed by Kathleen Harriman’s conduct as a journalist and her father’s confidential assistant in misleading Americans and the rest of the world about the genocidal deaths of the Polish prisoners and deportees in Stalinist Russia. And yet, she was not by any measure an evil person with bad intentions. She was an ordinary young woman from a very wealthy American family with no particular distinction as a journalist, apparently easily influenced by those around her and duped by Soviet propaganda and American propaganda produced by the U.S. government agency, for which she did volunteer work as a journalist. As someone who had never experienced any hardship in her young life, the thousands of dead bodies in the Katyn graves were, for her, a statistic rather than a tragedy for the victims, their families, and their country. Perhaps she would have reacted differently if the United States had lost a war, was under foreign occupation, and she was shown the bodies of thousands of murdered American military officers.

Her private letters reveal a rather callous attitude about her visit to the scene of the mass executions, but she definitely was not a participant in the larger geopolitical calculations which decided the fate of East-Central Europe. Still, by the accident of history, she had a chance to influence the future, and she did, but not by choosing to support the truth. It would have been highly unlikely for someone with her background and in her position to act differently. As Ambassador Harriman’s hostess at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow and his public relations assistant, she could hardly start a public disagreement with her father. Later, Ambassador Harriman put her in charge of organizing the logistics of the Yalta Conference, where the fate of millions of East-Central Europeans was decided. The “Big Three” summit sealed the loss of their freedom and made them Russia’s “captive nations” for several decades. It is almost certainly not what President Roosevelt, Ambassador Harriman, and his daughter wanted to happen, but they made it happen through their inexplicable trust in Stalin.

In the immediate sense, it was Kathleen Harriman’s reputation as a private media and U.S. government journalist that became significant because her presence in Katyn had an impact on how other Western correspondents reported on the massacre and how it was viewed by the State Department in Washington. A year before the Yalta Conference, her father, not a career diplomat but a millionaire businessman, apparently decided to use her skills as a news reporter to help convince officials in Washington that Stalin was a reliable ally and not a mass murderer because he knew that was what President Roosevelt wanted to hear. The same message was delivered to the Americans and the rest of the world by the Western correspondents in Moscow, who cited Kathleen Harriman’s name and her government position to boost the credibility of their reports. The same message was spread in the United States by the Office of War Information and abroad by the Voice of America.

It is possible that Kathleen Harriman’s decisions in January 1944, could have changed what became the outcome of the Yalta Conference. The “Big Three” summit went according to Stalin’s wishes because she had been unable to discover and report the truth about the Katyn massacre, or she had found it but failed to report it. She was only 26 when she authored her secret report for the U.S. government about the horrifying mass murders of Polish military officers. Her conclusion that the Germans had committed these murders helped to give official U.S. approval to one of Stalin’s most damaging propaganda lies of the twentieth century designed to hide his crime. Keeping his crime secret allowed him to get President Roosevelt’s approval for his demands of political arrangements and territorial changes for the period after the war, which otherwise he might not have been able to achieve.

The war atrocity of which Kathleen Harriman helped to absolve Stalin and the Soviet regime was a series of mass executions of nearly 22,000 Polish military officers, state workers, and intelligentsia prisoners of war carried out by the NKVD (“People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs,” the Soviet secret police) in April and May 1940. At first glance, a report by a 26-year-old journalist somewhere in the State Department’s files, may not appear highly significant, but it likely changed Poland’s history and helped bring immense harm to millions of other people in East-Central Europe. Hiding Stalin’s responsibility for the Katyn massacre from the Americans and the British public is what helped him get what he wanted from Roosevelt and Churchill at Yalta. Although the report itself was secret and available only to high-level U.S. officials, its significance was in supporting and augmenting the journalistic accounts that misled the public opinion in the United States and Great Britain.

Both Western leaders already knew Stalin had committed this war crime. What they did not want was for the opposition politicians and the voters in their countries to discover that the Soviet dictator, on whose promises they had relied at their wartime summit meetings, was a mass murderer, not much different from Germany’s totalitarian and genocidal leader Adolf Hitler. Reporting by Kathleen Harriman and American and other Western news correspondents based at that time in the Soviet Union helped to safeguard for a few more years Stalin’s reputation in the United States and Great Britain as a defender of liberty and democracy and a champion of social progress. These were also some of the main propaganda themes of the Office of War Information and the Voice of America during World War II and, in VOA’s case, even for a few years after the war.

Kathleen Harriman was never a full-time employee on the agency or the VOA payroll but worked for OWI and VOA as an unpaid volunteer. She did not need money, but she enjoyed the attention and prestige of working for the U.S. government’s war agency and her work as a journalist for private media in London. To her credit later, she did not try to provide false excuses for her mistake in her report from Katyn when called to testify before a congressional committee in 1952. Although she did not apologize for its impact on U.S. foreign policy and the victim’s families, her answers to questions from members of Congress were polite and much more honest and straightforward than those of former Office of War Information and Voice of America officials, whose responses were often incomplete and misleading. They appeared defiant and not at all ashamed of their misjudgments. During the war, some were responsible for producing OWI propaganda films justifying to Americans the illegal internment of U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry. The forced relocation of innocent American citizens, although not nearly as brutal and deadly as similar actions in Russia, was based on the Stalinist model of collective responsibility, and Stalin’s deportations of ethnic groups suspected of disloyalty to the Soviet state provided a blueprint for the Roosevelt administration for a solution to a problem that did not exist.

Kathleen Harriman made a mistake but did not violate any U.S. laws. However, senior OWI officials did, including future U.S. Senator Alan Cranston (Democrat – California), who had forced some Polish-American radio broadcasters to stop blaming the Soviet Union for the Katyn murders by illegally applying pressure on the owners of private radio stations in the United States in the violation of the First Amendment provisions against government interference with a free press. The Office of War Information officials also tried to shut down a Polish American newspaper, which pointed out that OWI distributed false and misleading information to American media about Polish war orphans who were transiting through California on their way to a refugee camp in Mexico (the Roosevelt administration did not allow them to stay in the United States and be adopted by Americans) to help hide information that their parents were murdered or died as prisoners in Stalin’s Russia. To prevent U.S. media from contacting the children and their guardians, the Roosevelt administration kept them under U.S. military guard in a former relocation center for Japanese-Americans near Los Angeles.14 The agency for which Kathleen Harriman volunteered became infamous for hiding the truth, misleading Americans and the world with pro-Soviet propaganda, and violating U.S. laws. In 1943, the highly displeased U.S. Congress, in a bipartisan vote, cut OWI’s domestic propaganda budget to almost nothing. In the middle of the war, Congress also cut funding for the Voice of America, but not as drastically. Considering the behavior of the leadership of the government organization for which she volunteered, it is hard to imagine that a 26-year-old would have had the knowledge and the boldness to question Stalinist propaganda, which the Office of War Information promoted on a daily basis.

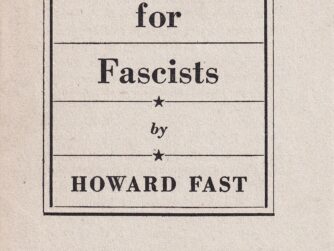

The Yalta Conference and the Katyn massacre were two history-changing events that have not lent themselves easily to helping advance the narrative of the Voice of America’s journalistic integrity in those years. Even though the station’s federal management likes to refer to the promise of always giving the world truthful news, journalists like Kathleen Harriman or VOA’s first communist chief news writer and editor Howard Fast, who in 1953 won the Stalin International Peace Prize (later renamed the Lenin Peace Prize), have been always omitted from the institution’s official history. The station also employed many foreign-born fellow travelers. The chief anti-U.S. propagandist in communist-ruled Poland, a denier of Stalin’s responsibility for the Katyn massacre, and a harsh critic of the U.S. Congress’s investigation of the Stalinist crime was a former United States Office of War Information and Voice of America editor Stefan Arski (employed by OWI and VOA as Artur Salman).15 His name also does not appear in any official VOA history or books documenting the organization’s early years, including Alan Heil’s highly hagiographic book, Voice of America: A History (Columbia University Press, 2003). Heil also does not mention Howard Fast, the misleading reporting on the Katyn massacre, and the later censorship of the Katyn story. Also not mentioned in any books about VOA is Mira Złotowska Michałowska16, a former OWI and VOA Polish editor who had returned to Poland, married a high-level communist diplomat, and translated Howard Fast’s books into Polish while publishing soft and misleading pro-Warsaw regime propaganda in such U.S. periodicals as Harper’s Magazine.17 But also never or rarely mentioned by most American historians and former U.S.-born Voice of America officials and journalists are anti-communist refugee journalists, women, and men, whom the Truman administration hired to replace the initial editorial team of Soviet and communist sympathizers.

The Voice of America’s record as a journalistic entity charged with providing truthful news to defend freedom has been mixed. It was far from perfect but included at least one spectacular success—the peaceful end of the Cold War. President Truman made it possible by demanding staffing and programming reforms at the U.S. government’s broadcaster. In Poland, until Ronald Reagan’s presidency, VOA’s role was not nearly as significant as that of the Polish Service of Radio Free Europe, which President Truman secretly helped to launch. After the Truman administration reforms of the early 1950s, VOA was somewhat more popular in the Soviet Union. However, communism in Poland fell because of strong and persistant internal opposition, including, the independent Solidarity trade union, and the economic and political decline of the Soviet Union. Not to be discounted in the collapse of communism and the Soviet empire was the consistent leadership provided by the United States government under both Democratic and Republican administrations from President Roosevelt’s death until the end of Reagan’s presidency.

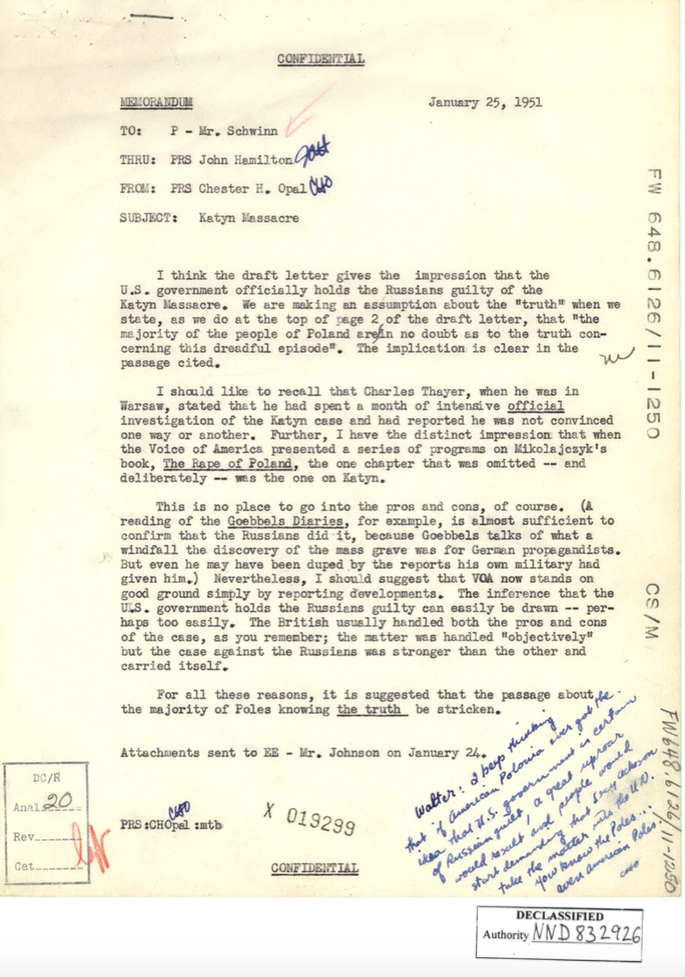

For a better understanding of how the Voice of America performed in the twentieth century, I would divide VOA’s history into two broad periods. The VOA broadcasters of the first period produced anti-Nazi propaganda, which did not appear effective in shortening the war. They also helped to bring communist rule and socialism to East Central Europe. The VOA broadcasters of the later period contributed to the fall of communism in East-Central Europe and the dissolution of the Soviet empire. I had the good luck and privilege to be working for VOA when it was no longer under major influence of Soviet propaganda, but even those successful decades can be divided into three different timespans with different levels of impact: 1. From the later years of the Truman administration when censorship in favor of the Soviet Union almost completely disappeared until the later years of the Eisenhower administration when it started to creep back; 2. From the later years of the Eisenhower’s presidency until the start of Ronald Reagan‘s presidency, when limited censorship was still applied from time to time to the Katyn story; 3. The Reagan years, which brought an end to such censorship.

The institutional censorship in the 1970s included banning Soviet Nobel Prize-winning author Alexandr Solzhenitsyn from being interviewed by the VOA Russian Service during Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations.18 In his monumental work, The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn wrote about the Katyn massacre. He blamed it on the Soviet leadership, which may explain why the VOA management would not allow long excerpts from his book to be read on the air. Such censorship against Solzhenitsyn and restrictions on extensive reporting about Soviet and other communist atrocities were never imposed by Radio Free Europe’s and Radio Liberty‘s American management.

VOA’s wartime journalists were different from those of the later period who were refugees from communism. The first group hired during World War II did not advance the defeat of Germany and Japan with their anti-Nazi and anti-Japanese, but also pro-Soviet and pro-Stalin propaganda. The Germans and the Japanese fought almost to the bitter end. Instead, the wartime Voice of America made Stalin’s communist takeover of East-Central Europe somewhat faster and easier than it otherwise might have been. From 1942 until about 1950—VOA supported communist dictators in the Soviet Union, China, and elsewhere in the hope that they would be most effective in fighting fascism, as well as facilitated Soviet Russia’s domination over East-Central Europe in the hope of securing peace and social progress after the war. From about 1950 until the end of the Cold War—VOA tried to reverse the mistakes of the first period and restore freedom and democracy in East Central Europe, Russia, and China, but without admitting any mistakes had been made previously and, from time to time, still using limited censorship to protect the policy of détente with the Soviet Union and its satellite countries. To better understand the overall U.S. government response to the Soviet betrayal of the Yalta agreements, one must also weigh in a much more robust and effective response to the Soviet and other communist propaganda from Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. Like VOA, they were also funded by U.S. taxpayers and initially secretly managed by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) but with considerable journalistic independence granted to their service chiefs, editors, and broadcasters—far more than at the Voice of America.

Kathleen Harriman is linked to the first period in VOA’s history and to the fellow travelers and Soviet agents of influence who had helped Stalin cover up his crimes and deceive the American President during World War II. These wartime U.S. government propagandists had also misled a large segment of the American public into believing that communist Russia was not a dictatorship but a noble experiment in a progressive democracy. Kathleen Harriman was part of the group of idealistic but naive journalists in the early years of VOA’s existence. If it were not for some independent private media and some members of Congress of both parties who raised the alarm over the domestic and international propaganda activities of President Roosevelt’s Office of War Information, the damage from the Voice of America wartime broadcasts glorifying Stalin and hiding or excusing his crimes could have been even greater and longer lasting. Kathleen Harriman’s mistake in absolving Soviet Russia of murdering Polish prisoners of war and the handling of her fateful report from Katyn by U.S. government officials were investigated, discussed, and condemned by a bipartisan congressional committee, the United States House Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation of the Facts, Evidence, and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, which was established in 1951 and held public hearings in 1952. Also known as the Madden Committee, after its chairman, Rep. Ray J. Madden (Democrat — Indiana), it questioned numerous witnesses, including Kathleen Harriman, and published extensive reports. However, the committee’s findings have also been later forgotten and omitted from the official VOA history.

Untangling the early history of the Voice of America and U.S. government propaganda operations, both domestic and international, is not an easy task because almost everybody who played any role in helping Stalin gain control over Eastern Europe and helping the Chinese Communists win power in China had a reason to hide it or present it later as legitimate U.S. foreign policy goals and objective and successful journalism. To her credit, Kathleen Harriman did not engage in such sophistry in her 1952 testimony before the congressional committee studying the Katyn massacre. Private sector journalists usually try to avoid calling attention to their mistakes. On the other hand, some U.S. government journalists and officials not only hide information from Congress and the American public but often feel the need to describe their failures as successes to justify their salaries and calls for increased budgets. Some government officials, journalists, and scholars writing books about the Voice of America may have worked for VOA or hoped to work for it or its government agency. This may explain the dearth of objective analysis. It may also explain the disinformation by former and current Voice of America officials about the history of VOA broadcasting during World War II and the unofficial ban on mentioning journalists like Kathleen Harriman and Howard Fast in connection with VOA because bad publicity may lead to more congressional scrutiny and could affect future funding. A former Voice of America director Sanford J. Ungar, who had served under President Clinton from 1999 to 2001, said in response to a question during a panel discussion on February 3, 2022, organized to commemorate the 80th anniversary of VOA’s first broadcast, that the information about Howard Fast, a World War II VOA chief English news writer and editor receiving the Stalin Peace Prize in 1953, was merely “amusing,” and that asking such questions amounted to McCarthyism. He implied that past critics of VOA were white supremacists. However, while it is true that the critics included some segregationist southern Democrats, most were moderate Republicans and Democrats, and some of the most credible critics were former Communists who became anti-communists but never renounced their support for liberal and progressive causes.

The majority of the members of the Madden Committee, which investigated the Katyn massacre and criticized the Voice of America operations during and after the war, were northern Democrats, as was the committee’s chairman. The Republican members were also from districts in northern states. When Kathleen Harriman testified before the committee in 1952, she did not thoroughly explain her participation in hiding the truth about Stalin’s crimes. While she was a cooperating witness, committee members may have felt sorry for her because of her young age in 1944 and being under her father’s influence. They should have pressed for more detailed answers. Later in her life, she tried to stay out of the public limelight. However, some of the other American reporters, who were silent about communist atrocities and helped to spread Soviet propaganda but were not called to testify, presented themselves or were later hailed in the United States as giants of truthful and objective journalism. One of them was Kathleen Harriman’s boss in London’s bureau of the Office of War Information, Wallace Carroll, who became a news editor in the Washington bureau of the New York Times (1955-1963) and subsequently editor and publisher of the Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel.

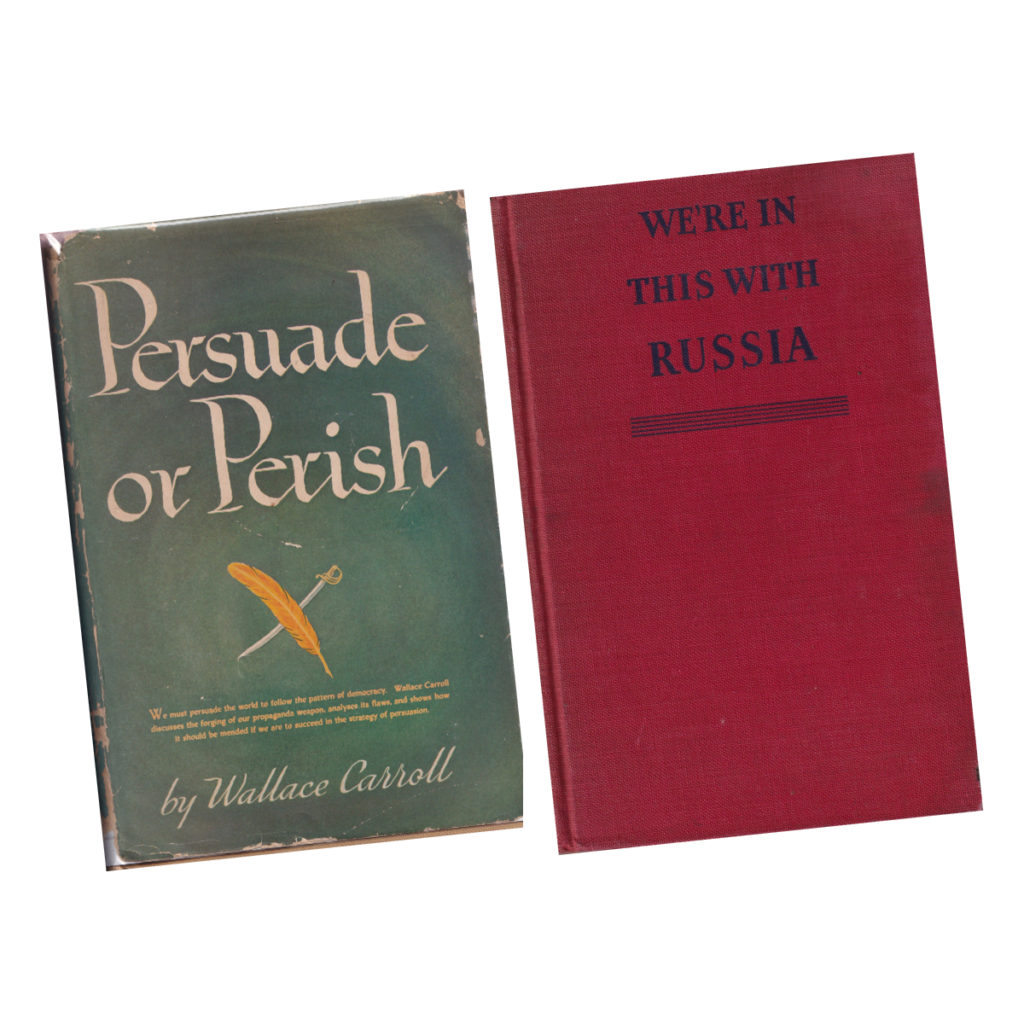

For a journalist who has acquired such a stellar reputation, even eight years after the Katyn Forest massacre, Carroll still defended one of Stalin’s greatest propaganda lies as truthful in his 1948 book, Persuade or Perish, designed to teach Americans how to recognize and fight propaganda. Yet this fact is strangely omitted from his biography by Mary Llewellyn McNeil, Century’s Witness: The Extraordinary Life of Journalist Wallace Carroll, published in 2022, even though she devotes several pages to discussing his Persuade or Perish book. The jacket of Century’s Witness includes a quote from Donald Graham, former publisher of the Washington Post, saying, “Only after reading this wonderful book, did I understand how great Carroll was.”19 His biographer, however, failed to mention that Carroll was duped by Soviet propaganda. If the Office of War Information should be blamed for brainwashing a young and inexperienced journalist like Kathleen Harriman to accept Soviet propaganda at face value, especially on the Katyn story, Wallace Carroll, her boss in London, would probably share most of the blame. His aggressive advocacy from London may have persuaded the OWI Director Elmer Davis that the Russians were telling the truth about Katyn. Elmer Davis then may have convinced President Roosevelt to place OWI and VOA in the forefront of defending Stalin’s innocence, although Davis never publicly admitted that he had discussed this issue with his boss in the White House.

The chances of Davis not speaking to Roosevelt about Katyn and giving him advice in line with the recommendations from his representative in London, Wallace Carroll, a naive journalist like Davis, seem very small. It would have been the advice Roosevelt wanted to hear since he rejected the opposite advice from others, even his closest friends. Carroll was correct in arguing in his earlier book, We’re In It With Russia (1942), that the Soviet Union would play a key role in defeating Germany militarily, but in that book, published after he had traveled to Russia in 1941 as a newspaper reporter, he also accepted and repeated without challenging many Soviet propaganda claims and did not warn that Stalin could not be trusted as America’s long-term ally. Instead, Carroll regretted that Stalin did not have a better public relations image in the United States.

This unwillingness to make intelligent use of the “capitalist press” was only one of a number of weaknesses in the Soviet propaganda organization. After all the commotion which has been made about Russian propaganda, I was surprised to find that the Soviets were overlooking many ways of influencing world opinion, not only through the press, but through the movies, the radio, and other media. They seldom missed a trick in the propaganda directed at their own people, but the machinery they employed to put their case before the world would have been considered inadequate by any other great power.20

Carroll vastly underestimated Stalin’s ability to manipulate the “capitalist press,” including his own writing, the Office of War Information, and the Voice of America. In his book, he repeatedly refers to warnings about Stalin, communism, and the Soviet Union as invoking “the Bolshevik Bogy.” Robert E. Sherwood used the same expression in a May 8, 1944 confidential telegram from London to Wallace Carroll at the OWI. Carroll, more than anybody else, could have influenced Kathleen Harriman’s view of the Katyn massacre even before she got to Moscow since he was in charge of the Office of War Information operation in London when she was working there as a volunteer.

When in April 1943, the Germans announced the discovery of the Katyn graves, Carroll strongly urged the OWI office in Washington to launch a major propaganda offensive to counter the German claim that it was a Soviet crime.21 Carroll later served in one of the top positions in charge of Voice of America programs. After the war, he was executive editor of the Winston-Salem Journal and Sentinel, served as news editor in the Washington bureau of the New York Times from 1955 to 1963, and was a member of the Pulitzer Prize Board. In his book, Persuade or Perish, published almost three years after the war, he still insisted that the Soviet version of the Katyn massacre was true. Carroll wrote in 1948:

... the dissension which was permitted to arise over the Katyn massacre was still working to the advantage of defeated Germany after the war. In July, 1946, more than three years after Goebbels opened his campaign, the German leaders on trial for war crimes at Nuremberg revived the allegations against the Russians in an obvious attempt to drive a wedge between the Soviets and the Western Powers.22

Wallace Carroll was utterly wrong and misleading by implying that the German leaders had revived the Katyn allegations against the Russians at the Nuremberg trials. It was the Soviet prosecutor at Nuremberg who had introduced the Katyn charges and tried to blame the mass murder on the Germans. It soon became apparent that the Russians could not prove their case with their poorly fabricated evidence. Seeing his claims refuted, the Soviet prosecutor quietly dropped the Katyn charges against the German defendants. These facts, which Carroll as a journalist could have easily checked with minimal effort by looking at news reports but failed to do so and did not present in his book, were confirmed to the Madden Committee by Robert H. Jackson, who, during his legal career, was United States Solicitor General, Attorney General, Supreme Court Justice, and chief United States prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials. Justice Jackson was an outstanding liberal jurist. Even though he was appointed to the Supreme Court by President Roosevelt, he was one of the dissenting judges in the 1944 Korematsu v. United States case brought by a U.S. citizen challenging the forced internment of Japanese-American citizens during the war. While the Office of War Information defended President Roosevelt’s decision, Justice Jackson argued that it was racially discriminatory and unconstitutional. The court’s majority sided with the Roosevelt administration. Some OWI officials, including Elmer Davis, claimed later that they were against the forcible deportations of Americans, but they may have been more concerned about how the Japanese could exploit them in their propaganda abroad against the United States. None resigned over this issue, and the agency, under their leadership, produced propaganda films supporting the internment policy and falsely claiming that the Japanese-Americans collaborated willingly in their imprisonment.

Justice Jackson was proven right when the Supreme Court in 2018 finally overturned the Korematsu decision. At the Nuremberg trial, he was not fooled by the fabricated Katyn evidence presented by the Soviet side. He explained to the Madden Committee how the Soviet prosecutor tried but failed to get the international tribunal to convict the Nazi war criminals for a war crime ordered by Stalin and other members of the Soviet Communist Party Politburo. In 1946, Justice Jackson knew that the Soviets were lying. Wallace Carroll, the celebrated journalist, still did not know it in 1948. Until 1981, the Voice of America was still afraid to accuse the Soviet Union of carrying out the Katyn executions. Another celebrated journalist, Harrison Salisbury, claimed he was still not certain in the 1980s that the Soviets had committed this atrocity.

STATEMENT OF HON. ROBERT H. JACKSON, ASSOCIATE JUSTICE, UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT [November 11, 1952] Chairman MADDEN. For the purposes of the record, Mr. Justice, would you state your name and your title? Mr. Justice JACKSON. Robert H. Jackson. At the present time I am associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. I was representative and chief of counsel for the United States at the Nuremberg prosecutions, at the international trial only. Chairman MADDEN. Do you have a statement you wish to read? ... Mr. Justice JACKSON. The first proposal that the Nuremberg trial should take up examination of the Katyn massacre came from the Soviet prosecutor during the drawing of the indictment. Preliminary drafts were negotiated in London at a series of conferences where I was represented, but not personally present. At the last London meeting, the Soviet prosecutor included among crimes charged in the east the following: In September 1941, 925 Polish officers who were prisoners of war were killed in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk. Both British and American representatives protested, but they finally concluded that, despite their personal disapproval, if the Soviet thought they could prove the charge they were entitled to do so under the division of the case. The indictment was brought to Berlin for final settlement and filing, where I objected to inclusion of the charge and even more strongly when, at the last moment, the Soviet delayed its filing by amending the Katyn charge to include 11,000 instead of 925 victims. ... The Soviet prosecutor appears to have abandoned the charge. The tribunal did not convict the German defendants of the Katyn massacre. Neither did it expressly exonerate them, as the judgment made no reference to the Katyn incident. The Soviet judge dissented in some matters but did not mention Katyn.23

Carroll does not mention in Persuade or Perish his Office of War Information volunteer London employee Kathleen Harriman. Her reporting contributions to OWI in Britain must not have been very significant. Still, while working in the London OWI office, when he was in charge, she had to be exposed to his pro-Soviet views and his uncritical acceptance of Soviet propaganda. In 1948, he repeated, without any challenge, the Soviet Communist Party Pravda newspaper’s denunciation of the Polish government-in-exile in London as “Hitler’s Polish collaborators”24 for asking the International Red Cross to conduct an impartial investigation to find out who had murdered thousands of Polish officers.

It would appear that even before going to Moscow with her father in October 1943, Kathleen Harriman had already received a strong dose of Soviet propaganda indoctrination in the OWI office in London before being exposed to more of it in Russia. The irony in Wallace Carroll’s 1948 Persuade or Perish book and in his role as one of the Voice of America’s “founding fathers” was that he had presented himself as a propaganda expert and bragged about his success in countering Nazi propaganda about Katyn after being completely duped by Soviet propaganda over this very issue not only during World War II but even three years after Stalin had established his brutal dominance over East-Central Europe and more evidence emerged that he had ordered the killings of the Polish POWs. On the cover of Persuade or Perish, Carroll was described as being in London “to direct psychological warfare operations in the European Theater and to supervise the American information program in the British Isles.” He had a falling out with the OWI deputy director Robert Sherwood and resigned from his position in London. Sherwood came to London to replace him after his own disagreements with the OWI Director, Elmer Davis. However, all three agreed on coordinating Soviet and American propaganda. In 1944, Carroll “returned to Washington to direct the planning of American psychological warfare operations over the entire European Continent,” the note said.

Therefore, in addition to being Kathleen Harriman’s boss in London, Wallace Carroll was later one of the numerous wartime officials responsible for Voice of America broadcasts to Europe who continued to cover up Stalin’s crimes at the end of the war and for a few more years after the war. Wallace Carroll, Robert Sherwood, and Elmer Davis were in charge of many wartime VOA journalists, Americans by birth and foreign-born, who were strongly pro-Soviet. Some were communist sympathizers, and probably more than a dozen were Communist Party members.

Carroll and other OWI and VOA executives had little regard for foreign refugee journalists unless they agreed with them and supported Stalin as much as the American management asked of them. In Persuade or Perish, Carroll praised the talents and enthusiasm of VOA’s “émigrés” but generally wrote about them disparagingly for having “passions and political convictions which sometimes proved too much for their good intentions.”

There was another fault of American propaganda from New York [Voice of America broadcast from New York until 1954] that we strove to overcome with just as little success—a fault that can only be described as the émigré imprint.25

Carroll’s lofty view of the “émigrés” was not dissimilar to FDR’s attitude toward the small East-Central European nations. Both thought they knew better what was good for the East Europeans. Both were convinced that Soviet Russia was socially progressive, even more than the United States, and deserved to be the region’s dominant power and guarantor of post-war peace. At least one émigré VOA broadcaster who dared to object to pro-Soviet propaganda about Katyn was threatened with dismissal.26 Konstanty Broel Plater resigned in 1944 in protest against VOA’s broadcasting of Soviet propaganda lies about the Katyn massacre.

One remarkable émigré journalist who did not yet work for the Voice of America during the war but who would become the VOA Russian Service chief in 1948 was Alexander Barmine, a former general in the Soviet military intelligence. He defected in 1937 from the Soviet Embassy in Athens, Greece, and was condemned to death in absentia in the Soviet Union. In an article published by Reader’s Digest in October 1944, he warned about pro-Soviet VOA officials and journalists like Wallace Carroll and Owen Lattimore but did not name them.

The United States is waging a deadly struggle against Nazi totalitarianism. All its energies, labor, wealth, thousands of its lives, are being sacrificed to destroy this enemy of democracy. Yet, at the same time, in the press, on the radio, in the Government and among liberal circles supposed to represent the vigilant conscience of the nation, there is in process a moral and psychological disarmament before another totalitarian conspiracy—that of the Communists—which threatens our democracy even more seriously. It is dismaying to see how our Left intelligentsia, swayed by subtle Communist propaganda, have transformed the triumph of superhuman fighting will of the Russian people into a triumph of the totalitarian Communist regime. The Russians had no choice but to fight under whatever regime they had, and they rightly decided that foreign tyranny would be worse than native. But what shall we say of American "democrats" who, instead of praising the Russian people and hoping they may reap the reward of freedom, praise the regime that oppresses them and compare it favorably with our democratic way of life? The unspeakable tragedy of the Russian people is that they are compelled to fight the foreign aggressor without any rights or liberties of their own. Every second family of these Russian fighting men has lost someone in a purge, or to one of the concentration camps in which at least ten million victims of the dictatorship are still enduring a living death.27

With approval and encouragement from the Truman administration, Barmine included reports about the Katyn massacre in VOA Russian broadcasts in the early 1950s.28

At least one American journalist in London during the war did not fall for Stalin’s lies about Katyn. It was not anybody connected with the OWI offices in London, Washington, or New York. In defending himself from false accusations by Senator Joseph McCarthy (Republican – Wisconsin), Edward R. Murrow pointed out in a CBS’ See It Now television program broadcast on April 13, 1954, that he had gotten the Katyn story right when it was first reported by the Germans. Murrow blamed it on the Russians. However, contrary to what some Voice of America officials and journalists still believe, he had nothing to do with the Office of War Information or the Voice of America during World War II and did not become the United States Information Agency (USIA) Director until 1961.

I require no lectures from the junior Senator from Wisconsin as to the dangers or terrors of Communism. Having watched the aggressive forces at work in Western Europe, having had friends in Eastern Europe butchered and driven into exile, having broadcast from London in 1943 that the Russians were responsible for the Katyn massacre, having told the story of the Russian refusal to allow allied aircraft to land on Russian fields after dropping supplies to those who rose in Warsaw -- and then were betrayed by the Russians—and having been denounced by the Russian radio for these reports, I cannot feel that I require instruction from the Senator on the evils of Communism.29

Soviet newspapers made Kathleen Harriman famous in Russia during the war when she was in Moscow with her father because Stalin and Soviet propagandists wanted to gain their support. She is now largely forgotten in Russia.

U.S. news reports in January 1944 listed Miss Harriman as being present in Katyn as a Moscow representative of the Office of War Information. This U.S. government agency was created in 1942 to be an authoritative source of war news for Americans and to produce radio information programs and propaganda for foreign audiences. Her affiliation with OWI gave the official stamp of approval for the only conclusion readers could draw from the news reports of American correspondents—the Soviet Union was innocent in this tragedy. This was the stated conclusion of the secret report Kathleen Harriman wrote to be sent by her father to the State Department. But her official report and the news reports by her colleagues were deceptive and wrong. She and the other journalists all became witting or unwitting participants in spreading a blatant Soviet propaganda lie.

The correspondents did not warn the American public that they were subject to severe censorship by Soviet officials and intimidation by the NKVD. Apparently, most did not believe in what they had reported or, at least, did not think the Soviets had proven their claims. Kathleen Harriman was in a somewhat better position than the other journalists because her diplomatic cable did not have to go through the Soviet censors. But she went even further in misleading U.S. government officials by presenting her own view in her secret report to the State Department that the Germans were responsible for carrying out the murders in Katyn.

The United Press dispatch, which appeared in American newspapers around January 16, 1943, after being delayed by the Soviet censors for several days, was typical of reports by Western correspondents who had gone with Kathleen Harriman on the trip organized by the Soviet government and supervised closely by the NKVD. It was most likely authored by the newly arrived UP correspondent Harrison Salisbury, later the first regular New York Times correspondent in Moscow after World War II, the first American journalist invited by the North Vietnamese government during the Vietnam War, and a Pulitzer Prize winner. In January 1944, Salisbury went with the group to Katyn, but some assumed that Salisbury’s UP Moscow boss Henry Shapiro wrote and sent the report.30 The headline of the UP report read:

Russia Hurls Charge: Nazis Murdered 11,000 Officials Aver.

Kathleen Harriman is prominently mentioned in the second paragraph of the UP dispatch, which also states that the murders occurred in 1941 and, therefore, much more likely to have been committed by the Germans.

The conclusions regarding the slaughter in 1941 were announced in the presence of 17 American, British, and Canadian correspondents and two representatives of the United States Office of War Information—Kathleen Harriman, daughter of the American ambassador to Russia and John Melby, acting Moscow chief of the OWI.31

There was nothing in the UP report on the circumstances of the Polish prisoners’ capture and detention by the NKVD, and, of course, nothing about Stalin’s other war crimes and communist atrocities. The report did not examine some of the significant weaknesses in the evidence presented by the Soviet government experts and had a most banal ending for a story about a human tragedy of such immense magnitude:

The correspondents were taken slightly less than 10 miles west of Smolensk to the Katyn Hills, rolling slopes above the Dnieper. The region is known locally as "Goat’s Hill" because goats grazed there in peace time.32

The Western correspondents and Kathleen Harriman deceived Americans and the world’s public opinion with a Soviet propaganda lie. Her failure as a journalist and, at the same time, a representative of the U.S. government in Soviet Russia should not, however, be judged too harshly. Nothing in her carefree life prepared her for the task she was given. Other journalists and political leaders—men older, much more experienced, and considerably more powerful and influential than her—failed even more spectacularly by allowing themselves to be fooled by Soviet communist dictator Joseph Stalin and his propaganda or, in many cases, knowingly using and spreading Soviet disinformation. Still, this 26-year-old journalist had a critical role in history at a highly decisive moment. She had an opportunity to discover the truth and most likely knew what it was, but—because of her father’s position, the pro-Soviet blindness of her Office of War Information bosses, Soviet propaganda influence, intimidation by the NKVD, and her self-interest—she made the fateful error of reporting what everybody who mattered to her seemingly wanted to hear.

But even if she had made different decisions as a journalist investigating the scene of a war crime, it is not clear whether it would have changed much that happened to the East-Central Europeans after the war. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was too determined to appease Stalin at all costs. He would have probably found a way to cast aside and hide any information that might have stopped him from giving the Soviet dictator what he wanted because he thought America needed his full cooperation and goodwill to defeat Germany and Japan and secure world peace after the war.

President Roosevelt was right about Germany if the lives of American soldiers were to be spared and the fighting and dying done mainly by the Russians. He was wrong about needing Russia’s help against Japan, but he could not have known that the atomic bomb would work. He was entirely and tragically wrong in assuming that Stalin would help the United States maintain peace and stability in international relations and allow some measure of democracy in Eastern Europe. In his plans for the post-war world, FDR relied on the word of a dictator and a mass murderer. Furthermore, the Red Army was already preparing to occupy the countries that Stalin wanted for himself and Russia. Stalin was unwilling to give up the territories he had already annexed once before, thanks to his 1939 alliance with Hitler’s Nazi Germany, which led to World War II. Still, President Roosevelt could have brought up the question of Stalin’s guilt in the Katyn massacre and demanded specific and enforceable guarantees of free and democratic elections in East-Central Europe. Whether this would have changed the course of history is anybody’s guess, but the Harrimans and the Western journalists who went to Katyn did not provide information with which he could have made such demands, assuming he would even want to use it.

Roosevelt’s decisions about Russia most likely saved the lives of many American soldiers in the short run and brought victory over Nazi Germany much faster. But his miscalculations before and during the Yalta Summit also had another profound impact— bringing Stalinist communism, death, suffering, and socialist poverty to millions of people for many decades. His decisions strengthened the Soviet Union as America’s ideological and military adversary. They helped Stalin to instigate the Korean War, with over 30,000 U.S. battle deaths and allowed Russia to start other wars and conflicts through its proxies. The Roosevelt administration’s concessions to Stalin, its support for the Chinese Communists, and the World War II pro-communist propaganda by OWI and VOA could also be blamed for setting the stage for the victory of the Chinese Communists and the Vietnam War, with over 58,000 U.S. military deaths in Vietnam, and a genocide in China. Other civilian and military Cold War casualties were also in the millions. Korea, Vietnam, and other Cold War conflicts cost the United States trillions of dollars. The Cold War was not cold.

Whether these deaths and suffering could have been averted if a young woman and a group of Western journalists had been courageous enough and found a way to tell President Roosevelt and Americans that Stalin was not much different than Hitler and Red Fascism was not much different from Black Fascism will never be known. They, together with Office of War Information officials and Voice of America journalists and editors, followed instead in the footsteps of Walter Duranty, another Pulitzer Prize winner, who lied in his reporting from Russia in the 1930s about the famine in Ukraine and attacked Welsh journalist Gareth Jones, who accurately reported that the starving of the Ukrainians ordered by Stalin took millions of lives.

However, very few progressive Americans have asked whether honest journalism by OWI and VOA during World War II, keeping these institutions free of Soviet agents of influence, and not relying on a report of a 25-year-old daughter of the U.S. businessman-ambassador to the Soviet Union could have made a difference for millions of East Europeans. This question is rarely posed because many politicians, scholars, and journalists do not want to damage the legacy of President Roosevelt and his administration, harm the Democratic Party in the United States, and, in general, cast doubt on progressive causes. What also should be said, however, is that the administration of President Harry S. Truman, who was a Democrat and Roosevelt’s Vice President, changed the course of history by resisting further Soviet aggression against other nations with the Truman Doctrine, the creation of NATO, and the Marshall Plan. President Truman abolished the Office of War Information in 1945 and placed the Voice of America in the State Department. He also supported the establishment of Radio Free Europe (RFE) and the initially secret U.S. government funding for its operations. The Truman administration also initiated significant management and programming reforms to make VOA broadcasts more effective against Soviet propaganda by hiring anti-communist refugee journalists. Despite decades of discrimination and renewed pro-Soviet censorship by new teams of American-born left-leaning managers and editors, they still managed to undo some of the damage done by the original group VOA’s Stalin’s admirers and fellow travelers.

For her personal role in shaping history, what Kathleen Harriman was asked to do as a journalist and her father’s emissary had a much more profound impact than her volunteer work for the Office of War Information and later for the Voice of America when both institutions were still strongly pro-Soviet and engaging in spreading disinformation about communism in Eastern Europe. A year before the Yalta Summit, at her father’s request, she helped Stalin hide from the Americans and the rest of the world his responsibility for one of his most gruesome genocidal murders—the extermination of thousands of Polish military officers held in Russia as prisoners of war, including prominent members of Poland’s political and intellectual elites. She did some unspecified volunteer work for the Voice of America when President Truman had already started changing U.S. policy toward the Soviet Union, but before VOA hired such anti-communist journalists as future Russian Service chief, former Soviet military intelligence General Alexander Barmine, who had defected in 1937 and joined VOA in 1948. The same year, VOA hired Zofia Korbońska, a former anti-Nazi Polish resistance member, at the recommendation of former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane.33 Ambassador Lane, a former elite American diplomat, and former OWI refugee editor Julius Epstein played a crucial role in getting the U.S. Congress to start the Katyn investigation. Thanks to President Truman’s “Campaign of Truth,”34 VOA’s new emigre journalists like Zofia Korbońska were able to begin correcting the lies about Katyn initiated by the Kremlin and embraced and amplified earlier for Americans and the world by Ambassador Harriman, his daughter, Western reporters in Moscow, and the early officials, editors, and journalists at the Office of War Information and the Voice of America.

What is unclear and perhaps will never be clear is whether, at his father’s request and with his help, Kathleen Harriman wrote her infamous report absolving Stalin of responsibility for the Katyn war crime, with both knowing or strongly suspecting it contained a false conclusion, or whether they were both tragically influenced by Soviet propaganda and inexplicably arrogant and naive. It was, however, the finding President Roosevelt expected them to deliver, and they may not have wanted to disappoint him. FDR believed, not unreasonably, that it was in U.S. political and military interest while fighting Germany and Japan to keep Russia at war, maintain the wartime alliance, and prevent Stalin from seeking a separate peace with Hitler. He was also willing, however, in trying to accommodate Stalin’s demands, to sacrifice the interests and territories of the smaller allies in the anti-Nazi coalition, such as Poland, without their knowledge and agreement.

The crime, for which Ambassador Harriman and his daughter assigned the blame to the wrong totalitarian dictator, became collectively known as the Katyn Forest massacre, after an area near Smolensk in western Russia, where the German Army discovered in April 1943 some of the graves of thousands of Polish military officers who had mysteriously disappeared in the spring of 1940 when they were prisoners of war in the Soviet Union. The massacre’s victims were active duty and reserve Polish Army officers captured by the Red Army in September 1939 when Hitler and Stalin jointly attacked and divided Poland under the secret terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed in Moscow on August 23, 1939. Many prominent Polish leaders were among the murdered reserve officers. Among the killed in all the 1940 NKVD executions were 14 Polish generals, 20 university professors, and more than 100 writers and journalists. A military pilot Janina Lewandowska, a daughter of a Polish general, was the only woman POW executed during the massacre at Katyn, but more women were killed at other execution sites. About 8% of the Katyn massacre victims were Polish Jews[efn]Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (New York: Basic Books, 2010), p. 140.[/efn_note], including Baruch Steinberg, Chief Rabbi of the Polish Army.

The Katyn murders were only one of several mass executions of Polish prisoners, military and civilian, carried out by the NKVD secret police in the spring of 1940 at various locations in the Soviet Union. After Hitler broke his alliance with Stalin and invaded Russia in June 1941, the German Army occupied the sites where the Polish POWs were secretly buried. In the spring of 1943, the Germans only discovered the Katyn graves. The locations of the graves of several thousand more Polish victims of the 1940 Soviet executions were still unknown. An international commission of experts convened by the Germans in 1943 issued a report on April 30, stating that the Russians had committed the Katyn murders. After the Red Army retook the area in September-October 1943, the Soviet government established a commission of its experts to prove the massacre of Polish prisoners was a Nazi war crime.

Kathleen Harriman went to Katyn in January 1944 on a trip for foreign journalists organized by the Soviet authorities as one of two U.S. Embassy and Office of War Information representatives. The Soviets would not have organized the show and invited Western journalists if they had not been sure they could deceive them or otherwise get them to agree with the Soviet version of the crime because of self-interest, indoctrination, intimidation, or outright blackmail. They made the same assumption about Kathleen Harriman and her father, who were under additional pressure from President Roosevelt and his pro-Soviet advisors not to do anything that might upset FDR’s personal relationship with Stalin and Russia’s participation in the war. The consequences of publicly disagreeing with the Soviet government on this issue would have been most profound for the journalists. They knew they could be expelled from Russia and face severe reprisals from the Soviet secret police. For Ambassador Harriman’s and his daughter, accusing the Soviet Union of committing a major war crime would most likely bring an immediate end to their stay in Moscow. They would be asked to leave by the Soviet government, President Roosevelt, or both.

Averell Harriman most likely already knew that the Russians had killed the Polish officers, as did FDR. Neither wanted this information to reach Americans, especially the Polish-American voters. Kathleen Harriman and the other journalists almost certainly knew that the Soviet Commission’s presentation was a farce and that its members and other officials were lying about who had committed the crime, but none had the courage to put it in their respective reports. None wanted to be expelled from Russia, and none wanted to leave Russia to write a truthful news report and never be permitted to return.

The fact that the Western correspondents in Moscow did not believe in what they had reported after their visit to Katyn was confirmed for the Madden Committee by a Roman-Catholic priest, Father Léopold L. S. Braun (1903-1964). He was a member of the North American Province of the French Assumptionist Order (Augustinians of the Assumption). Since March 1,1934 to December 27, 1945, under a diplomatic agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union, Father Braun served as chaplain to the American Catholics working at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow and to other permanent and temporary Western residents in the Soviet capital. He was also a priest at the St. Louis des Français Church, located across the street from the infamous NKVD Lubianka prison. As assistant to French Bishop Pie Neveu, apostolic administrator of Moscow and senior foreign Catholic prelate in Russia during that period, Father Braun was invited to live at the French embassy compound, except for the period of three years from 1941 to 1944 when the French Vichy government recalled its ambassador to the USSR. His semi-diplomatic status and contacts with Western ambassadors and other diplomats protected him to a large degree from open reprisals by the Soviet secret police. His access to Western diplomats, Soviet officials, and ordinary Russians made him one of the best-informed foreigners in Moscow. Before arriving in Russia, he spoke fluent English and French and knew German and Spanish but did not speak Russian. He had to learn the Russian language, study Russian literature, and familiarize himself with Soviet life. Throughout his stay in the Soviet Union, he was constantly harassed by the NKVD.

In his extensive and excellent testimony on February 7, 1952, Father Braun told the committee that after the Western journalists went to Katyn in January 1944, he had talked to many of them but not to Kathleen Harriman. He was questioned by Congressman Thaddeus M. Machrowicz, who was a Polish-American Democrat from Michigan. Born in 1899 in Prussia to a Polish family in a town now in modern-day Poland, Machrowicz emigrated to the United States with his parents when he was three years old. He served in Congress from 1951 to 1961. He resigned from Congress after being appointed federal district judge in Michigan.

TESTIMONY OF FATHER LÉOPOLD BRAUN, A.A., NEW YORK, N.Y. Mr. MACHROWICZ. All right. Now, I believe you testified that you knew of the delegation of foreign correspondents who were taken to the Katyn Forest. Father BRAUN. Yes. Mr. MACHROWICZ. Did Kathleen Harriman join that group? Father BRAUN. I know that when the press body was invited to go to the Soviet demonstration, shall be call it, or investigation, the Ambassador's daughter got to know about it and manifested an interest in accompanying this press body there. That I happened to know. Mr. MACHROWICZ. Is there anything else that you know that you can tell this committee of any value relative to that group that went to the Katyn Forest? Father BRAUN. Not having been there, personally, I have nothing to say that could elucidate that question. Mr. MACHROWICZ. Is there anything you know on the basis of any conversations you had with any of the group that went to the Katyn Forest? Father BRAUN. For example? Mr. MACHROWICZ. Well, did any of the group indicate to you its conclusions? Father BRAUN. I know this, that practically every one of the American gentlemen who represented the American press, having returned from this trip—not a single one was convinced of the Soviet demonstration. That I know. But I never talked to Miss Harriman following her trip and I have nothing to say with regard to her testimony, not having spoken to her directly. Mr. MACHROWICZ. That is exactly what I wanted to know. You have answered my question.35

Earlier, during Father Braun’s testimony, he made an interesting and largely accurate observation about officials in Stalinist Russia deciding who would get visas to visas to visit the Soviet Union.

Father BRAUN. As a method of general procedure, the Soviet Government allows into that county people whom they can rely for propaganda purposes exclusively.36

The Soviet Foreign Ministry and its diplomats abroad were not always correct in making that assumption while issuing visas to foreigners, but officials in Russia worked hard, using bribery, intimidation, and blackmail to subvert visitors who were of particular interest to the Kremlin or the NKVD.

Congressman Machrowicz asked Father Braun whether he knew Ambassador Harriman and Miss Kathleen Harriman.

Father BRAUN. I knew them very well.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Did she have any diplomatic post at that time?

Father BRAUN. To my knowledge, Miss Harriman had no diplomatic post as such.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. Did she hold office, any office, any office that you know of, in Moscow?

Father BRAUN. I am inclined to think that she was employed in some undetermined manner in the OWI, which is the Office of War Information.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. You say you are inclined to think that she was. Do you know whether she was?

Father BRAUN.I don't definitely know whether or not she was officially employed, and if she was, in plain English, on the payroll, if that is what you mean.

Mr. MACHROWICZ. What leads you to that conclusion?

Father BRAUN. Well, because she was the Ambassador's daughter, you see.37

In the unpublished version of his memoirs, In Lubianka’s Shadow: The Memoirs of an American Priest in Stalin’s Moscow, 1934-1945, Father Braun wrote that the United States Office of War Information”greatly contributed to the spreading of plain Bolshevism under color of mutual cooperation for military ends.”38 However, this comment did not refer specifically to Kathleen Harriman’s volunteer work for OWI. He used her name when he described how she had intervened on his behalf to arrange for his travel out of Russia on a U.S. government plane and praised her as being “much liked by everybody.” However, in another part of his memoirs, he is highly critical of her report from Katyn sent to the State Department but does not identify her by name as its author. He was evidently trying to protect her reputation.