In 1941, President Roosevelt appointed Professor Owen Lattimore, who advocated for a stronger Soviet role in China, to serve as U.S. advisor to Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek, a position he held for one and a half years. The 1943 Official Register of the United States listing persons occupying administrative and supervisory positions in the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of the Federal Government, and in the District of Columbia Government, as of May 1, 1943, showed Owen Lattimore as Pacific Bureau Director at the Office of War Information San Francisco Regional Office, and thus responsible for Voice of America broadcasts to Asia, including China. In 1944, Lattimore was named OWI deputy director in Washington in charge of all Pacific programs but resigned at the end of the year to return to Johns Hopkins University.

Professor Lattimore is one of several founding fathers of the Voice of America, whose names have been written out from VOA’s official history. These officials and journalists eagerly embraced Soviet propaganda and supported Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin during World War II and, in some cases, even after the war’s end. After the start of the Cold War, their names started to disappear from books and articles about VOA.

Robert Conquest, a British-American historian who meticulously documented Stalinist crimes in his books The Great Terror: Stalin’s Purges of the 1930s (1968) and The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivisation and the Terror-Famine (1986), wrote about Owen Lattimore that he “was another noted apologist for the Stalin and similar regimes.”1 The other noted apologist named by Conquest in his book next to Lattimore was a British-American journalist, Walter Duranty, who, in his reports from the Soviet Union for The New York Times, lied about the famine in Ukraine engineered by the Soviet regime. The famine, known as the Holodomor, took the lives of several million Ukrainians.

Conquest noted that in the journal Pacific Affairs, which Lattimore edited, he wrote in the September 1938 issue that the Soviet show trials of the 1930s were an example of Soviet democracy in action because they “give the ordinary citizen more courage to protest, loudly, whenever he finds himself being victimized by ‘someone in the Party’ or ‘someone in the Government’.”2

Lattimore added, “That sounds to me like democracy,”3 and explained that he based his opinion on the accounts of Western correspondents in the Soviet Union.

The accounts of the most widely read Moscow correspondents all emphasize that since the close scrutiny of every person in a responsible position, following the trials, a great many abuses have been discovered and rectified.4

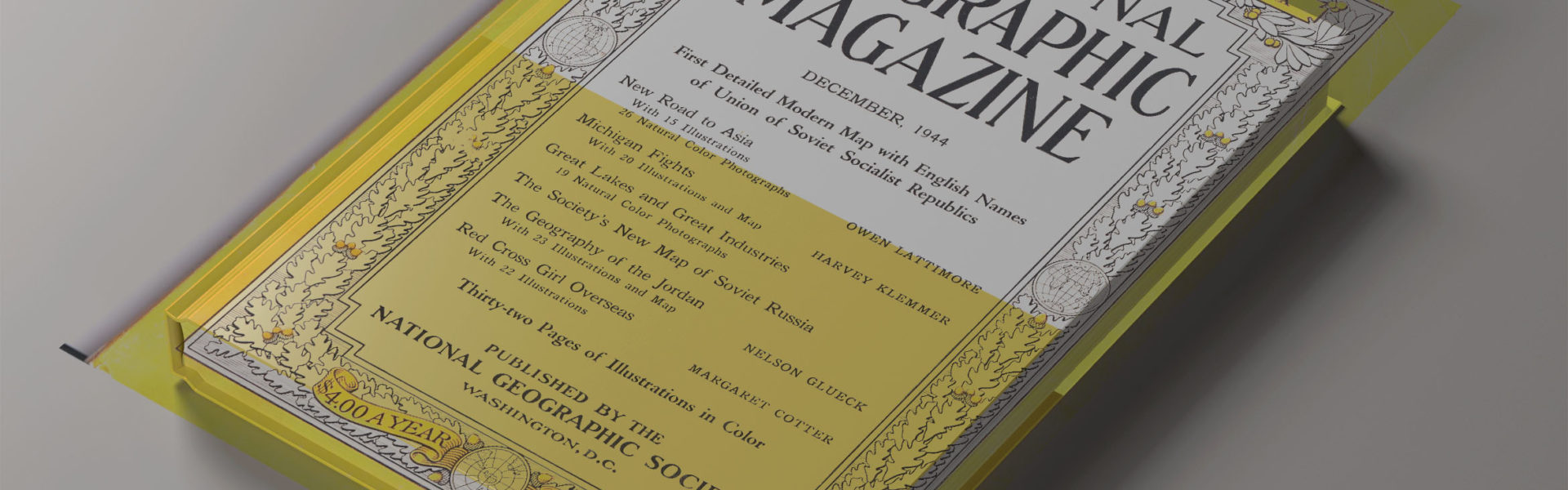

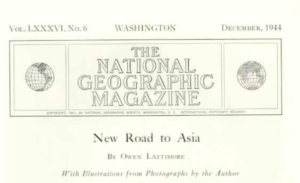

Under Owen Lattimore and other Soviet sympathizers who were duped by Soviet propaganda, World War II Voice of America broadcasts to China and other countries presented Stalin as a champion of democracy and progress. But Prof. Lattimore also propagandized to Americans in an article published in December 1944 in the National Geographic Magazine about his visit to the Soviet gold mines in Kolyma as a high-ranking Office of War Information official in the entourage of U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace.

Owen Lattimore on “Greenhouse Vitamins for Miners” in the Soviet Gulag

Owen Lattimore’s article, which appeared in the December 1944 issue of the National Geographic Magazine, may offer a hint of what kind of pro-Soviet and pro-communist Voice of America broadcasts to China and other countries in Asia were produced when he held key executive positions at the U.S. Office of War Information. Lattimore published the article after accompanying U.S. Vice-President Henry A. Wallace on his trip to Siberia, China, and Mongolia in 1944. The Soviet handlers took the American delegation to the Gulag gold mines, where, before and after their visit, Stalin’s prisoners were kept under the harshest conditions, and hundreds of thousands were worked to death. For the sake of the visiting Americans, the Soviet authorities transformed the work camps shown to the delegation into Potemkin villages. Well-fed and well-dressed NKVD guards, which appear in a photograph taken by Lattimore and used by National Geographic to illustrate his article, were substituted for slave laborers. The Gulag camps’ shops were filled with food and goods never before seen at the sites. Lattimore was either deliberately lying or wholly convinced this was a typical Soviet enterprise. He wrote for American readers in his National Geographic article about the concern shown by the communist authorities for the health of the Soviet workers:

Greenhouse Vitamins for Miners

We visited gold mines operated by Dalstroi in the valley of the Kolyma river… . It was interesting to find instead of sin, gin, and brawling of an old-time gold rush, extensive greenhouses growing tomatoes, cucumbers, and even melons, to make sure that the hardy miners got enough vitamins!5

The Voice of America, under the direction of such OWI officials and journalists as Owen Lattimore, Joseph Barnes, Wallace Carroll, John Houseman, and Elmer Davis, was deceiving not only foreign audiences. Some also misled millions of Americans at home about Soviet Russia and the Communists in China. Even though members of Congress, who were alarmed about the executive branch using government funds to propagandize to Americans, eliminated in 1943, in a bipartisan vote, almost all of OWI’s domestic propaganda budget, some of these fellow traveler-journalists were still promoting in the United States their highly deceptive views of Stalin and communism thanks to having easy access to U.S. radio networks, newspapers, and magazines.

Owen Lattimore compared the Dalstroi (also written as Dalstroy – Far North Construction Trust) “to a combination of Hudson’s Bay Company and TVA.” 6 He wrote that the workers he saw had volunteered for war but were ordered to stay because of Russia’s need for gold.7 He described in glowing terms the head of Dalstroi, Mr. Nikishov, as a recent recipient of the Order of Hero of the Soviet Union. He added that Mr. Nikishov and his wife “have a trained and sensitive interest in art and a deep sense of civic responsibility.”8 Near the Gulag camps, where thousands of prisoners died, the American delegation was entertained by “a fine ballet group from Poltava, in the (sic) Ukraine.” Lattimore quoted one member of President Wallace’s delegation as saying, “high-grade entertainment just naturally seems to go with gold, and so does high-powered executive ability.”9 Ivan Fedorovich Nikishov was a Soviet NKVD Lieutenant General.

For those Americans who were not well-informed about Soviet Russia, such articles by an Office of War Information and Voice of America U.S. government executive made it easier to accept or tolerate President Roosevelt’s decisions to make political and territorial concessions to Stalin at the expense of the people in Eastern Europe and helped Moscow establish pro-Soviet governments in the region to rule over them for more than forty years.

Henry Wallace withdrew his support for the Soviet Union during the Korean War. In an article written in 1952, Wallace called the Soviet Union a country “utterly evil,” a term similar to the “evil empire” that President Reagan used against Soviet Russia many years later.10

Russian hospitality is proverbial, and it is not surprising that on this occasion the Russians should do everything possible to impress the Vice-President of the country which was sending them so many billions of dollars of vital necessities of many kinds. So on the whole these visits made a most favorable impression on me. But, as I now know, this impression was not the complete one. Elinor Lipper, who was a slave laborer in the Magadan area for many years, has subsequently described the great effort put forth by the Soviet authorities to pull the wool over our eyes and make Magadan into a Potemkin village for my inspection. Watch towers were torn down. Prisoners were herded away out of sight. On this basis, … a false impression. I was amazed that the Russians could do so much in such short time—as was Wendell Willkie, who had visited the same region in 1942. But unfortunately neither Willkie nor I knew the full truth. As guests we were shown only one side of the coin.11

Even after the publication of Wallace’s article, Owen Lattimore remained unapologetic and, in a patronizing manner, accused Elinor Lipper of becoming a pawn in Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist witch hunt.

Elinor Lipper, born in Belgium in 1912 to a German-Jewish family, was a Communist Party member, first in Germany, where she studied medicine and was wanted by the Gestapo, and later in Switzerland, where she married a Swiss citizen to avoid being exiled. She later traveled to the Soviet Union and was arrested in 1937, merely two months after her arrival. Convicted of engaging in counterrevolutionary activities, she spent most of her sentence in the Kolyma Gulag, where she worked as a nurse. Through the intervention of the Swiss government, she was released in 1948 and allowed to leave the Soviet Union. In 1950, she published a book, Eleven Years in a Soviet Prison Camp, and went on a lecture tour in the United States.12

In the authorized English translation of her book from the original German, Elf Jahre in sowjetischen Gefängissen und Lagern (Zurich, Verlag Oprecht, 1950), inserted a two-page subsection on Owen Lattimore Report from Kolyma:

If his report to the Office of War Information was in substance the same as this article [“New Road to Asia” in the National Geographic Magazine, December 1944], the Office could scarcely have profited by his work. … Instead of telling us what he has seen, he hands out unexamined Soviet propaganda.13

In 1944, the Office of War Information included the “Voice of America” broadcasting operations and Owen Latimore was in charge of VOA and other information programs targeting countries in Asia, including China.

Elinor Lipper refuted one by one Lattimore’s assertions in the National Geographic magazine, including his comparisons of the Soviet Gulag gold mines to “a combination Hudson’s Bay Company and TVA [Tennessee Valley Authority].” Lipper wrote:

But the Hudson’s Bay Company is not run by the police nor does it make use of forced labor. Furthermore, neither the Hudson Bay Company nor the TVA shoots its workers if they refuse to go to work.14

As to Owen Lattimore’s statement that Mr. Nikoshov, the Soviet head of the Kolyma mines, and his wife “have a trained and sensitive interest in art and music, Elinor Lipper asked, “What would Dr. Lattimore think of a man who, having visited the Nazi camps of Dachau and Auschwitz, afterwards reported only that the SS commandant of the camp had ‘a sensitive interest in art and music’?”15

In the early 1950s, Owen Lattimore’s reputation was damaged by unsubstantiated accusations by Senator Joseph McCarthy (Republican – Wisconsin) that he was a Soviet intelligence agent. Senator McCarthy embellished and misinterpreted what Alexander Barmine, the former Brigadier General of the Soviet Army’s military intelligence and the then chief of the Voice of America Russian Branch (from about 1948 until 1964), said about Lattimore while testifying under oath before the United States Senate’s Special Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws, 1951–1977, known more commonly as the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS) and sometimes the McCarran Committee after its chairman, Senator Patrick Anthony McCarran (Democrat – Nevada). Barmine, who after his defection in 1937 from the Soviet Embassy in Athens was sentenced to death in absentia in the Soviet Union, told the subcommittee on July 31, 1951, that his boss in the Soviet military intelligence, General Yan Karlovich Berzin, had identified to him two Americans as “our men,” which, if true, meant that they were or could have been Soviet agents. Berzin, a Latvian Soviet communist, was shot during Stalin’s Great Purge of 1938.

According to Barmine, Joseph Fels Barnes and Owen Lattimore were the two men. From 1932 to 1934, Barnes was a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune based in Moscow and Berlin, and in 1942-1943 was in charge of Voice of America broadcasts. They both vehemently denied they were Soviet agents or spies.

Barmine was firmly convinced that Barnes and Lattimore were Soviet agents of influence. Still, he was careful to point out that his information about their possible work for the Soviet military intelligence was only based on what others had told him. He could not offer any concrete evidence to back up such an allegation.16

Prof. Owen Lattimore described Alexander Barmine’s testimony before the Senate’s subcommittee chaired by Senator McCarran as “one of the flimsiest yarns I have ever heard.”17 He added that Barmine “had bobbled the play” in his statements. Lattimore insisted:

Of course, I have never been connected with Soviet Military Intelligence in any way, shape or form, in any year A. D. or B. C.18

The information made public by Barmine could not be corroborated with documentary evidence, although several other witnesses testifying before congressional committees claimed Barnes and Lattimore had been either Soviet sympathizers or Communist Party members. Alexander Barmine also told the McCarran subcommittee that while working as an advisor for Reader’s Digest, he convinced the editors not to publish an article by Owen Lattimore, which he described as presenting the straight communist and Soviet line “camouflaged,” as he put it, “in very devious ways.” 19

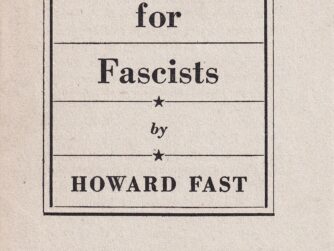

When General Berzin reportedly described Barnes and Lattimore to Barmine as “our men” who could be of help to him in his intelligence work in China, he might have been bragging without any factual basis or meant that these Americans could provide a journalistic cover to hide the real nature of Barmine’s GRU mission, just as Latimore’s article in the 1944 issue of National Geographic obscured slave labor in the Gulag camps, Barnes’ reporting from the Soviet Union in the 1930s minimized the Red Terror, and Howard Fast’s censorship at the Voice of America helped to protect Joseph Stalin from being seen as a brutal dictator. Howard Fast, a best-selling author, a Communist Party USA activist, and a future recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize, resigned under pressure from his position as the Voice of America chief news writer and editor, in effect, the job of VOA’s first news director, and left federal government employment in 1944.

After Robert Conquest’s The Great Terror was published in 1968 and reviewed by other scholars, including a review by British literary critic John Gross in The New Statesman newsmagazine, Prof. Lattimore, then with the Department of Chinese Studies of the University of Leeds, took exception to criticism and wrote in a letter to the Editor:

It is not mentioned that Mr. Wallace was then Vice-President of the United States, that he was on an official goodwill mission, and that he was accompanied by a suitably large party. … Is it assumed that a visit of this kind affords an ideal opportunity to snoop on one’s hosts?20

Lattimore objected to how Gross analyzed for The New Statesman what the British critic called the grotesque whitewashing of Stalin:

Perhaps the most extraordinary concerns Henry Wallace and Owen Lattimore, who actually visited Kolyma in 1944 and were given a VIP reception by the commandant, the unspeakable Nikishov, and his wife (herself an NKVD officer). Both men later published lyrical accounts of what they had seen. … Lattimore was especially struck by the Nikishovs’ ‘trained and sensitive interest in art and music’ and their ‘deep sense of civic responsibility’.21

Prof. Lattimore said in his letter to the Editor of The New Statesman that Conquest and Gross were trying to blame him for not writing “an intelligence report ‘exposing’ what one has not seen.” He added, “It is hard, sometimes to remember those days when the Russians were saving us all.” He ended his letter with a warning against “a possible second wave of Joe McCarthyism” reemerging in America after the 1968 U.S. presidential election should Democratic Party candidate Hubert Humphrey lose to Republican Party nominee Richard Nixon.

Robert Conquest responded to Lattimore’s letter with his own, in which he wrote that he was “not concerned with blame as such so much as with showing the nature and extent of the falsehood it is possible to get intelligent men to accept, or propagate.” He noted that when Prof. Lattimore published his article in The National Geographic Magazine, evidence about the true nature of Kolyma was already available.

There were many accounts from, among others, Poles (equally our allies) released under the 1941 agreement.22

John Gross also responded to Lattimore’s letter:

My objection, to put it mildly, is that while ‘good will’ may have necessitated keeping quiet, it didn’t oblige him to publish an article in a popular magazine describing Kolyma as though it were the promised land.23

Gross also wrote that Lattimore’s “humour at the expense of Miss Lipper (who suffered for years where he was entertained for days and published the truth where he transmitted the official fake) was equally misplaced.”

In his letter, Lattimore described Elinor Lipper’s book as “honest,” as far as he could tell, and “certainly a moving one.” But he noted that while the original German edition of her book did not include his name, “but when the English translation was published in America, the Joe McCarthy hue and cry was already on, so lo and behold there was a new, interpolated passage. (I still wonder who put her up to it.)” 24

Robert Conquest responded to Lattimore’s claim that criticism of his writings smacked of McCarthyism by pointing out that “McCarthyism consisted of lying about people,” but added that it is equally “inappropriate” and “a declaration of intellectual and ethical bankruptcy—to shout ‘McCarthyism’ at criticism based on irrefutable, or at any rate, unrefuted facts.”25 Conquest added:

Lattimore was himself slandered by McCarthy. But this not give him total and lifelong immunity from censure on other points.26

NOTES:

- Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: A Reassessment, Rev. ed. of the 1970 ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 486.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Owen Lattimore, “The Moscow Trials,” Pacific Affairs, VOL. XI, No. 3, September 1938, p. 371.

- Owen Lattimore, “New Road to Asia,” National Geographic, December 1944, p. 567.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 642.

- Ibid., p. 657.

- Ibid.

- Henry A. Wallace “Where I Was Wrong”, The Week Magazine, September 7, 1952, https://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2013/02/henry-a-wallace-1952-on-the-ruthless-nature-of-communism-cold-war-era-god-that-failed-weblogging.html.

- Ibid.

- José Vergara, “11 Years in Soviet Prison Camps,” Crime or Punishment: Russian Narratives of Incarceration, accessed June 19, 2023, https://crimeorpunishment.jvergara.digital.brynmawr.edu/crime-or-punishment/11-years-in-soviet-prison-camps.

- Elinor Lipper, Eleven Years in Soviet Prison Camps (London: The World Affairs Book Club, 1950), p. 114.

- Ibid., p. 115.

- Ibid., p. 117.

- Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Russian Branch Chief Alexander Barmine Was An Ex-Soviet General and Ex-Spy Who Testified Before Senator McCarthy – Page 9 – Ending Censorship of Katyn Massacre,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), April 17, 2023, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-russian-branch-chief-alexander-barmine-was-an-ex-soviet-general-and-ex-spy-who-testified-before-senator-mccarthy/.

- The New York Times, “Lattimore Assails ‘Flimsiest Yarn’,” August 2, 1951, p. 4, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1951/08/02/88440253.html?pageNumber=4.

- Ibid.

- Institute of Pacific Relations.: Hearings before the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, pp. 212-213, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d02120505q?urlappend=%3Bseq=223%3Bownerid=13510798903345995-227.

- Owen Lattimore, “Letters to the Editor,” New Statesman, October 11, 1968, p. 461.

- John Gross, “The Years of the Purges,” New Statesman, September 27, 1968, pp. 397-398.

- Robert Conquest, “Letters to The Editor,” The New Statesman, October 18, 1968, p. 496.

- John Gross, “Letters to The Editor,” The New Statesman, October 18, 1968, p. 496.

- Owen Lattimore, “Letters to the Editor,” The New Statesman, October 11, 1968, p. 461.

- Robert Conquest, “Letters to the Editor,” The New Statesman, October 18, 1968, p. 496.

- Ibid.