By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

Soviet influence at Voice of America during World War II — documents and analysis

Soviet influence at WWII Voice of America

From VOA to communist regime journalist

Choices of VOA’s pro-Soviet journalist

VOA journalist marries Communists

A pro-Soviet propagandist at OWI and VOA

VOA communist partner Stefan Arski

Pro-Soviet collaborators at OWI and VOA

A VOA friend of Stalin Peace Prize winner

Among Soviet sympathizers at VOA

Critics of her communist influence at VOA

Was she VOA’s communist ‘Mata Hari’?

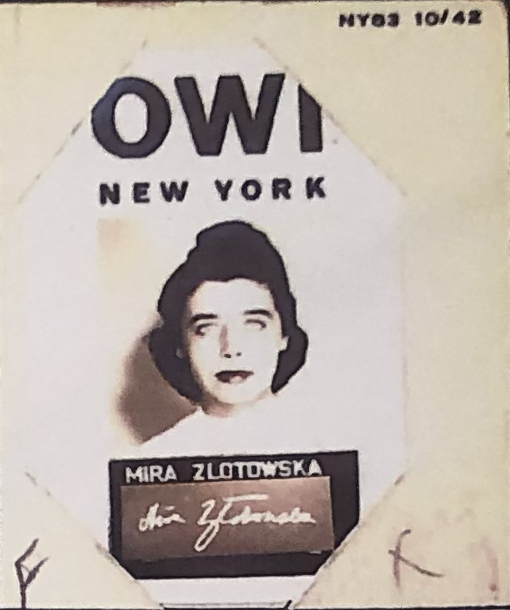

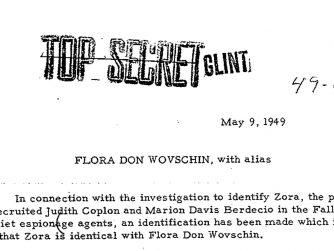

Mira Złotowska, later known as Mira Michałowska who published books and articles in English as Mira Michal and used several other pen names, was one of many radically left-wing journalists who during World War II worked in New York on Voice of America (VOA) U.S. government anti-Nazi radio broadcasts but also helping to spread Soviet propaganda and censoring news about Stalin’s atrocities. While not the most important among pro-Soviet propagandists at the Voice of America during the war, Michałowska later went back to Poland, married a high-level communist diplomat, and for many years supported the regime in Warsaw with soft propaganda in the West while also helping to expose Polish readers to American culture through her magazine articles and translations of American authors. One of the American writers she translated was her former VOA colleague and friend, the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize winner Howard Fast who in 1943 played an important role as VOA’s chief news writer. Despite today’s Russian attempts to undermine journalism with disinformation, the Voice of America has never officially acknowledged its mistakes in allowing pro-Soviet propagandists to take control of its programs for several years during World War II. Eventually, under pressure from congressional and other critics, the Voice of America was reformed in the early 1950s and made a contribution to the fall of communism in East-Central Europe.

Geopolitics, censorship and journalism in post-war Poland

If pro-Soviet former Voice of America journalists like Mira Złotowska and Stefan Arski were right and honest about anything, both while they worked for the U.S. government in New York and later when they returned to Poland to support the government controlled by pro-Moscow communists, these early VOA propagandists were right that any armed resistance against the Red Army troops and the regime’s army and militiamen would have been both bloody and pointless. The Polish Catholic bishops and most political leaders in Poland and abroad quickly came to the same conclusion on their own. Nearly all Poles, regardless of their political views, wanted to see their country rebuilt after the killings and the devastation of World War II. Poland’s Primate, Stefan Wyszyński, was even willing to have a dialogue with the regime as long as the basic principles of faith and freedom were not compromised. He had the full backing of other Polish bishops, including Kraków’s Archbishop Karol Wojtyła, future Pope John Paul II. Despite his agreement not to oppose the regime, the Communists imprisoned Wyszyński from September 1953 to October 1956 and launched a media campaign against the Catholic Church.

Media attacks on the Church slightly eased after 1956 and later resumed. When I interviewed Cardinal Wojtyła for the Voice of America during his visit to the United States in 1976, two years before he became Pope, he still had to speak in cautious and coded language, but he said pointedly that people everywhere in the world were hungry for God, for liberty and for the truth.[ref]Ted Lipien, “‘Hunger for God and Love’: Interview with Cardinal Wojtyła,” TedLipien.com, http://tedlipien.com/blog/2010/10/16/hunger-for-god-and-love-interview-with-cardinal-karol-wojtyla-future-pope-john-paul-ii/.[/ref] While Catholic and non-Catholic Poles knew that not even Wyszyński and Wojtyła could openly declare the regime illegitimate, they also knew that, unlike the communist media, the Polish bishops did not lie to them. Everyone in Poland also understood that the Soviet Union to a large degree controlled the communist regime and dictated the limits of public discourse and tolerance, which were somewhat greater in Poland than in the USSR. If state-employed journalists did not want to constantly lie, they had to specialize in non-political reporting on topics of general human interest, which was the path chosen by Mira Michałowska. When she wrote for Americans, she used soft political propaganda to drum up support for the communist regime.

While far above some of the most strident communist propagandists, she and other more liberal regime journalists did not rise to a level of intellectual honesty the Poles could get from the Church or from Radio Free Europe broadcasts. When the Communist Party allowed them some limited freedom of expression briefly after 1956 and again in the 1970s, fully independent newspapers still could not be published in Poland. Catholic Church publications, constantly harassed and printed in limited numbers, likewise could not cross certain lines.

What journalists like Mira Michałowska did was to create an illusion of a free press in a communist state. Being more worldly than some of the hardline regime media hacks, they correctly identified a niche of unmet demand for Western information. Being well-connected with the ruling communist elite, they knew what the censors would allow to be published during different periods of communist rule. To the state’s economic and propaganda benefit, and their own, they filled the niche which could not be completely served by Radio Free Europe which had no technical ability to broadcast television. There were Polish émigré newspapers and book publishers in the West, most notably Kultura in France, but newspapers and books could not be smuggled to Poland in large numbers. Regime journalists would argue that what they were doing was better than nothing, and it was true to some degree for many people, including themselves. However, as soon as communist censorship disappeared, their special role and value to the regime disappeared with it. They were only important for as long as communist censorship existed in Poland and the power of the Soviet Union kept it in place.

A communist ambassador’s wife

After returning to Poland shortly after the war to report for Harper’s Magazine, Mira Michałowska’s pro-regime propaganda work in the United States continued in the 1950s and the 1960s in a new role. As the wife of Polish communist diplomat Jerzy Michałowski, whom she had married in 1947, Mira Michałowska hosted diplomatic receptions in New York and Washington and, according to various rumors and publicly made allegations, may have done a little bit of spying on American diplomats for the communist government in Poland. This activity may have started even earlier when her husband was posted as the regime’s ambassador to London and might have been just routine gathering of information and reporting to Warsaw about contacts with important foreigners, which Polish communist diplomats and their spouses had to do, or perhaps something much more, involving an illicit love affair and sharing of diplomatic secrets. None of these rumors can be unraveled without access to still secret Polish and U.S. intelligence files, some of which in Poland may have been destroyed. It would not be surprising, however, that her ability to develop multiple friendships with well-known figures in the world of actors, artists, writers, journalists and politicians in Great Britain and in the United States in the Cold War era caught the attention of intelligence and counterintelligence services. According to an article published this year in Poland, there are 1,600 pages in the communist regime’s intelligence file pertaining to Michałowska. The author claims that she herself was constantly monitored by the regime’s intelligence service.[ref]Piotr Oczko, “Wybór Miry. O Mirze Michałowskiej, Miesięcznik Znak, nr 769, June 2019.[/ref]

Whether she was or was not a real spy will remain for now without a definite answer. The spying accusations against her, which at the time were raised in a few minor American newspaper articles and mentioned by at least two members of the U.S. Congress, cannot be definitely proven with any currently publicly available documentary evidence. Very few people in the United States or in Poland remember these rumors. Practically, no one has heard about them because, although not secret, they were never widely publicized even at the time when they were made. Mainstream American media did not report on them to the best of my knowledge. Communist media in Poland would completely ignore such reports, unless they wanted to ridicule them. I did not find any indication that they did in her case. If mainstream American media did not report on these accusations, the Voice of America would almost certainly ignore them out of the station’s management’s overwhelming concern for not damaging U.S.-Polish diplomatic relations. While Radio Free Europe would have reported on any serious serious cases of communist espionage, as would VOA, allegations against Michałowska, which could not be proven with any documents or witnesses, apparently did not qualify as sufficiently newsworthy even during the Cold War. Partially archived recordings of RFE Polish Service broadcasts accessible online from Polish Radio’s “Radia Wolności” (“Freedom Radios”) website do not show any results when searching for Michałowska’s or her husband’s names.[ref]PolishRadio.pl, “Radia Wolności,”https://www.polskieradio.pl/129,Radia-Wolnosci, accessed December 8, 2019.[/ref]

In her book published in English, she revealed that she and Jerzy Michałowski met for the first time in 1946 when she was covering the United Nations Security Council meeting in Lake Success, New York “for a weekly magazine” and he was “a deputy delegate from Poland.”[ref]Mira Michal, Nobody Told Me How: A Diplomatic Entertainment (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1962), 15.[/ref] Whether at that time she was still married to Professor Złotowski is unclear. The weekly magazine she was reporting for was Time. Her entire book written for English speakers as gossip and subtle propaganda is remarkably void of any references to the government in Warsaw as being controlled by a pro-Soviet Communist Party. There is no mention of the lack of political and cultural freedoms in Poland or the fact that her husband who was named ambassador to Great Britain had at some point joined the Communist Party. As one reviewer of her book observed, “there is not one hint of the Cold War in these pages.” [ref]Kirkus Review, undated, https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/mira-michal/nobody-told-me-how-a-diplomatic-entertainment/.[/ref]

It is generally assumed that as the wife of a Polish ambassador, Michałowska had to report in some form to the regime’s intelligence service on her contacts with Westerners of special interest, although at least one journalist in Poland claims that she had consistently refused such requests This claim seems highly improbable, especially when she and her husband were abroad in the early years of the Cold War. Even Voice of America journalists had to report to their security office on all their contacts with diplomats from communist bloc countries. Whether she was an active participant in intelligence gathering operations against the United States, as it was alleged in the late 1960s, may, however, never be known with any degree of certainty, but her family and other defenders insist that she had refused to spy on her Western friends.[ref]Piotr Oczko, “Wybór Miry. O Mirze Michałowskiej,” Miesięcznik Znak, nr 769, June 2019.[/ref] Her refusal was tolerated, they claim, because she was the wife of an important regime ambassador. They also claim that the regime and the Communist Party never fully trusted Michałowski and his wife. This claim seems difficult to reconcile with the fact that the couple was representing the regime in London during the most paranoid period of Stalinist rule in Poland in the 1950s. The mistrust may have developed somewhat later.

Family members also said that when her husband was no longer in diplomatic service, she was requested to spy, refused, and in retaliation for her refusal was prevented by the regime for a number of years in the 1970s to travel abroad to visit her friends. Some of these claims cannot be confirmed without access to still secret government intelligence files, but it would be highly improbable that she would have been able to refuse all cooperation while still at a diplomatic mission abroad. Such a refusal would have been especially dangerous during the period when her husband was the ambassador to Great Britain while Poland was ruled by the notoriously repressive Stalinist regime headed by Bolesław Bierut. The whole system of communist rule was based on a fear of spying by the West and on the regime’s own spying on Poland’s citizens and accusing its political opponents of being Western agents and Nazi sympathizers.

In my research, I did not find any mention or proof that Michałowska was herself a dues-paying member of the Polish United Workers’ Party, a Communist Party known in Poland as Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza (PZPR), but I also did not find in any of her writings I have reviewed any direct criticism of the party or the communist system in Poland, or criticism of the Soviet Union. Her family claims that she never joined the Communist Party. Her diplomat-husband was, however, a Communist Party member and, according to her family, was expelled from the party in the early 1970s as part of the communist regime-inspired anti-Semitic purge which started in 1968. He served as the regime’s ambassador in the United States until July 1971.[ref]Sue A. Kohler, Jeffrey R. Carson, Sixteenth Street Architecture (Volume 2), (Washington: The Commission of Fine Arts, 1988), 515.[/ref] The family claims that he was forced to retire early (he was 62) because he was Jewish on his mother side. Neither he nor his wife claimed their Jewish heritage or emphasized it in any way, but anti-Semites within the Communist Party leadership were targeting Jews in and out of government regardless of whether they proclaimed their ancestry or were communist non-believers. According to a recent article published in Poland, their children did not find out about their partial Jewish roots until they were nearly adults.[ref]Piotr Oczko, “Wybór Miry. O Mirze Michałowskiej,” Miesięcznik Znak, nr 769, June 2019.[/ref]

What was newsworthy and what was being reported by Radio Free Europe from the 1950s on were the communist regime’s attempts to subvert and split Polish ethnic and refugee organizations abroad. Like all regime diplomats and their spouses, Michałowska had to contribute to this effort. These attempts ultimately failed for the most part, but at the time they looked particularly threatening to anti-regime Poles living in exile. However, most Polish journalists working in exile also understood that diplomatic relations and various forms of exchanges between Western countries and Poland were necessary and, if conducted under scrutiny, could help Poland gain a small measure of freedom even under Soviet domination. They also supported some of the strategic goals of benefit to Poland, which the regime diplomats also worked on, such as the recognition of Poland’s western borders. However, Polish journalists still viewed regime diplomats with some contempt while recognizing that in bilateral exchanges and business deals, its embassies could not be bypassed as the authorities maintained a strict control over who could or could not get visas to travel to Poland.

Michałowska’s role as the wife of a diplomat was to organize embassy receptions and engage in other forms of public diplomacy to win greater support in the West for the regime and improve its reputation, which involved using soft propaganda to manipulate public opinion, particularly in two Western countries, Great Britain and the United States. In the historical context of the period before the Cold War ended, Polish people needed friends in the United States more than ever, but such friends did not have to be also good friends of the communist authorities, although in some cases they could not avoid dealing with the regime. That is where Michałowska played an important role as the wife of the ambassador. This soft propaganda role could not have been played without using disinformation. Because the regime lacked popular support and legitimacy, certain facts had to be hidden and lies and half-truths had to be used on naive Westerners. This is quite evident from her book about being the wife of the regime ambassador in London and in New York at the UN. She presented Poland as a normal country ruled by a normal government and represented abroad by a normal diplomatic service. She may have become convinced, however, that it was also normal to mislead her Western readers since she was working on getting both sides together, Americans and pro-regime reformists, in an effort to benefit Poland, and perhaps also America, Russia and the cause of global peace. A lot of self-interest no doubt also played a significant role.

At that time, as events in Hungary in 1956 and in Czechoslovakia in 1968 had shown, Poland could not be taken out of the Soviet orbit without risking a bloody Soviet military invasion of the country or perhaps even a nuclear war with the West. Several options available to the Poles were: to withdraw into private life; to strongly but peacefully resist the communist regime through strikes, protests, underground publications and listening to the reformed Voice of America and to even more honest, journalistically superior and much more hard-hitting Radio Free Europe; to work with the system to try to topple it down from within; or to work within the system as supporters or more or less loyal participants while trying to reform it through mild criticism and limited exposure to Western ideas and culture. Michałowska chose the latter path and never altered her course, while many others, including some former communists, sooner or later, switched sides and joined the open opposition or left for exile in the West. Warsaw regime ambassador to the United States, Romulad Spasowki, initially an ardent Communist, defected to in 1981 in protest against the introduction of martial law by General Wojciech Jaruzelski. The regime confiscated his family’s property and condemned him to death in absentia. In 1989, Spasowski’s death sentence was revoked. In 1993, Polish President Lech Wałęsa restored Spasowski’s Polish citizenship. Ambassador to Japan Zdzisław Rurarz also defected in 1981.

A co-creator of regime TV

Somewhat related to Mira Michałowska‘s public role abroad was her busy journalistic and writing activity in Poland, which was welcomed by many in the country as bringing some previously banned Western ideas and culture to the Poles. Others and even those who enjoyed reading her articles also saw it, however, as the regime’s cynical attempt to manipulate and control state media and public opinion for its own safety and ultimate benefit.

There were definite limits to what Michałowska could and could not write. The only fully uncensored sources of information for the Poles in Poland were Radio Free Europe, and to a lesser extent the BBC and the Voice of America. Even VOA journalists after the war were still restricted at various times by the management on how far they could go in reporting highly critical information about the communist governments in East-Central Europe or even about the Soviet Union. Radio Free Europe fortunately never practiced similar censorship and was the Western radio station most feared by the communist authorities in Warsaw.

By helping the party and the government develop modern television programs in Poland, Michałowska would have contributed to the creation of less harsh but at the same time more effective political and non-political propaganda to help the communist elite maintain their hold on power and to keep her position of importance to the authorities in charge of the country. These modernized and slightly more free regime media after 1956 were designed to lure the Poles away from listening to Radio Free Europe. This attempt failed as the Poles continued to listen to RFE and VOA in increasing numbers, but the Communist Party tried hard to prevent that number from becoming even larger and having an even greater impact on the population.

The rationale for loosening some of the media censorship was that if the Poles were going to learn about the West, it would be better if they learned about it from Michałowska through her cultural reporting rather than from RFE and VOA because ultimately, she still had to follow the rules imposed by the communist censors on all journalists and writers who wanted to have their work published in Poland. Not surprisingly, this model has been greatly advanced and improved in today’s Russia by Vladimir Putin and his propagandists. Putin is using the same tactics to either silence journalists who criticize his rule, or he buys them off. This includes not only Russian journalists but also some media commentators, news reporters, and think-tank analysts in the United States and in other countries.

Most of Michałowska’s writing in the later years of the Cold War can be viewed from different angles, as helpful to both the regime and her Polish readers, but there is little doubt that through her work at the Voice of America and later at Time and Harper’s magazines during and immediately after World War II, Michałowska had made her most significant contribution to the propaganda effort by Soviet sympathizers in the United States to help win support for the installation of a pro-Soviet communist government in Poland. She may have later regretted it, but to my knowledge she never admitted publicly that she did, even when she could have safely say it later in her life.

Role and reputation in Poland

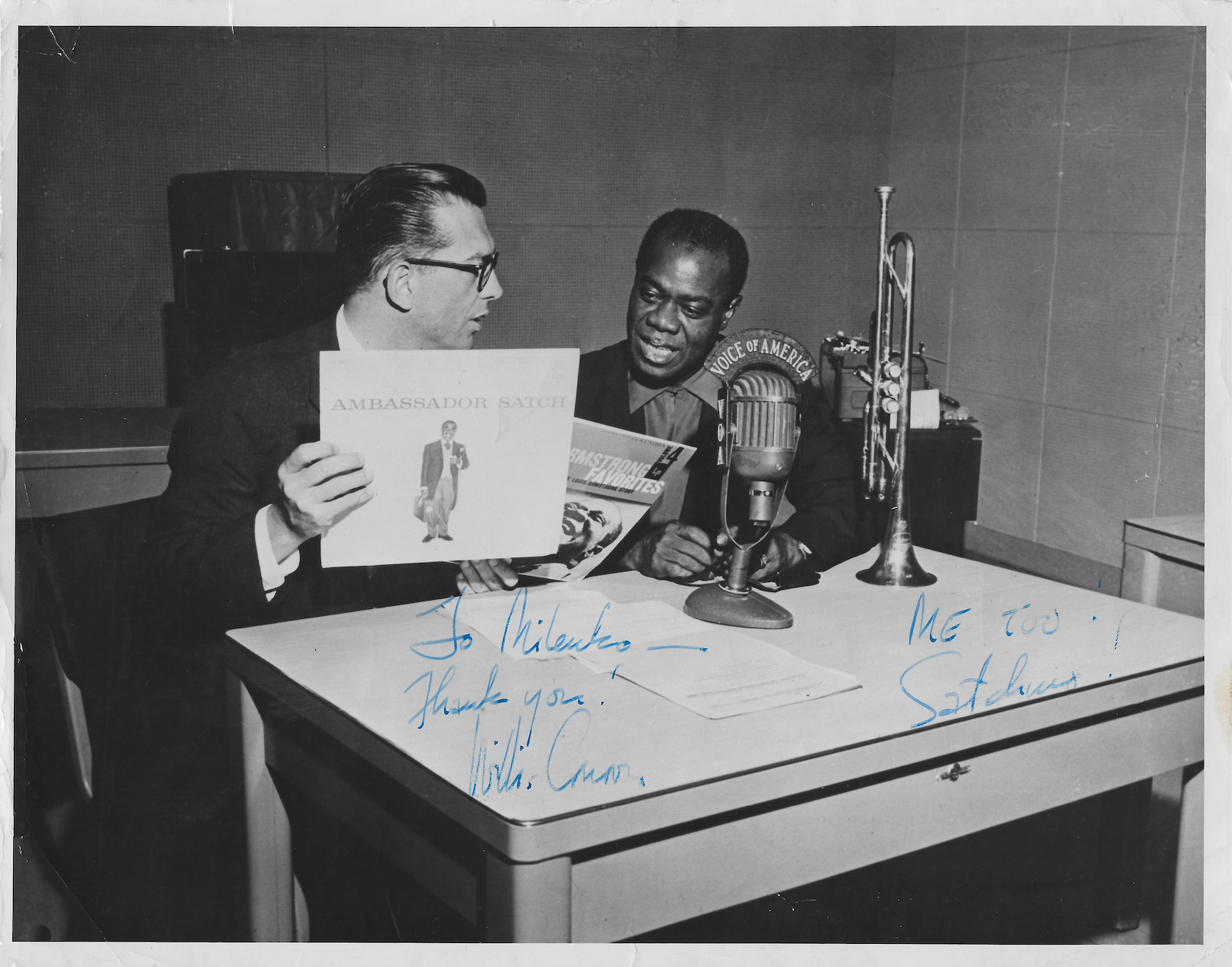

Mira Michałowska is generally well regarded in Poland as the author of popular articles written for the weekly magazine Przekrój which under communism had a reputation of being pro-Western and promoting Western culture, including American jazz. At the same time, the Voice of America was airing Willis Conover’s jazz programs, which in the 1950s also became highly popular among audiences in a Poland, in the Soviet Union and in other Soviet Block countries seeking news about new trends in Western culture. In her own way, Michałowska was doing public diplomacy for the United States, but it could also be said that with her various journalistic activities, she and other less dogmatic journalists employed by the state provided a safety valve for the regime. Because of her knowledge of Western media, regime officials consulted her in the 1950s on how to create some of the first television programs in Poland. Przekrój articles written under her pen name Maria Zientarowa, full of sharp humor and irony about the life of two fictional Polish families, were later published in two books and turned into a highly popular 1960s television serial. She penned about a dozen popular novels and translated books by several American authors.

The communist authorities understood the need for allowing creative individuals, even those who could not be fully trusted or controlled, to function within the system, thus preventing them from joining the open or underground opposition. Within the restrictions of censorship, the regime needed them to write for popular magazines and appear in radio and television programs to distract the rest of the population from the grim realities of life under the socialist economy. Following the Stalinist period some subtle humor against the communist system and limited exposure to Western culture were tolerated, as was some investigative journalism as long as none questioned the illegitimacy of the regime and the Communist Party or criticized the Soviet Union and its leaders. Within these limits, some of these more talented individuals who made an important contribution to cultural life in Poland under foreign-imposed communism, perhaps in some ways undermined the system while at the same time perhaps also helping it to survive longer than necessary.

It is not easy to make an overall assessment of their role because for as long as the Soviet had troops in and around Poland and were willing to use them, the system could not be changed or even substantially reformed. Regime journalists like Michałowska deceived themselves and their readers by claiming or pretending that it could be reformed even under Russia’s tutelage. Polish workers and Solidarity labor union Lech Wałęsa who listened to Radio Free Europe and Voice of America broadcasts knew that it could not be reformed, but they generally limited their demands and tried to negotiate with the regime while waiting for the right moment to bring about its downfall without resorting to violence and causing bloodshed. Their intellectual advisors, many of whom were left-leaning, as well as the Catholic Church hierarchy, advocated for compromises and a gradual transition to democracy. Michałowska is not associated in Poland with this group.

In presenting Western cultural news to her readers in Poland, While Michałowska did not highlight in her articles and books her previous U.S. government employment and her work at the Voice of America. During the Cold War, publicizing this part of her biography could have been harmful for her literary career even if she had described herself as a progressive, left-leaning VOA broadcaster in support of what became the communist government in Poland. When it became safer after the death of Stalin in 1953 and the regime change in 1956 to a more tolerant but still repressive communist rule, she presented herself as a good friend of Americans and a promoter of American literature. It no longer required courage or carried any significant risks being viewed as an expert on American culture and a moderate supporter of more contacts with progressive Americans who were not hostile toward communism and the government in Warsaw. Post-Stalinist communist governments in Poland were generally in favor of good relations with the West that would benefit their ailing state economy while at the same time not straying from the foreign policy line dictated by the Soviet Union. Gradually, even the Communist Party leadership realized that allowing U.S. and other Western politicians and artists to visit Poland and promising friendlier ties with the West helped its image In the country and abroad.

By translating American authors, Michałowska contributed in her own way to making America more familiar to the Poles and gained some respect and popularity in Poland. It could be said that in her own way she also countered anti-American propaganda produced by hardline regime journalists, including her former VOA colleague Stefan Arski. Despite her earlier political writing and choices, she was not later a one-dimensional writer and journalist but appeared to be a rather complex and conflicted personality, which was true also of many other talented Polish writers, artists and intellectuals. Not all of them could or wanted to escape to the West. Realizing their own, similar dilemma, some of the prominent left-leaning political dissidents in Poland also saw her in that light and socialized with her despite her much closer regime connections, both her own and through her husband, a communist diplomat. It does not appear, however, that at any point she openly joined and was active in the anti-regime opposition movement by publishing in the underground press or participating in anti-regime demonstrations, as many of her left-leaning liberal friends eventually did. She chose to work within the communist system, even if she at times appeared to work against it or at least perhaps tried to see it reformed.

However, largely because of her secretiveness, only few people in Poland have heard of Michałowska as someone who had created propaganda for both the U.S. government and the post-war communist regime in Poland, was married to a high-level communist official or was accused by some Americans of spying. Most Poles remember her as a good writer of generally non-political and interesting articles and novels. Yet for a period of time, this charming, vivacious, mysterious and well-connected woman played an important role in the realm of World War II and Cold War propaganda, politics, and most likely also political espionage.

A tribute from a regime journalist

When Mira Michałowska died in 2007, Daniel Passent, another former pro-regime journalist, like her regarded as a reformist for the system that was ultimately unreformable, praised her for winning for Poland many friends in Great Britain and in the United States. He also described her as being a shining jewel in gray and sad Warsaw.[ref]Daniel Passent, “Mira,” EnPassant, August 30, 2007, https://passent.blog.polityka.pl/2007/08/30/mira/.[/ref] They both served the same regime that produced both grayness and above all sadness for many Poles, which does not mean that millions of people in Poland during the Cold War did not lead lives that were meaningful in terms of personal happiness, entertainment and even many fulfilling careers that did not require excessively difficult moral choices. Writers, journalists, most academics and some artists, however, were put in a position of having to make sometimes painful compromises to get well-paying jobs and have their work published or performed in their respective fields. Poland, even under Soviet domination, still needed local press and television journalists for everyday domestic news and information that Radio Free Europe could not easily fully provide since its reporters were completely banned by the regime. If they could somehow appear in Poland (all RFE visa requests were refused), they would be arrested and put on trial. Ironically, the visa ban protected RFE from the visa blackmail which the regime used to put pressure on and try to influence other Western journalists, including during various periods VOA reporters. Today authoritarian regimes in Russia, Iran, China, North Korea, Cuba and in several other such countries still use such visa and dual citizenship blackmail against journalists, making the knowledge of its past use once again critical for today’s news organizations.

With some of the best exile writers and reporters being banned from visiting Poland, as members of the communist elite, Michałowska and Passent were able to gain positive publicity as authors of articles and books with somewhat more liberal and reformist messages than those produced by the regime’s more hardline supporters among other journalists and writers. Perhaps they both wanted to see the system gradually change through a convergence of Polish-style communism with some form of left-wing Western liberalism. In the end, it did not happen despite some gradual loosening of political repression in response to protests, strikes and demonstrations. In 1981, the communist regime introduced martial law under pressure from the Kremlin and workers’ strikes organized by the Solidarity trade union. Within a decade, communism in Poland collapsed. Mira Michałowska’s usefulness to the regime and the regime itself had reached their end, mostly because the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev no longer had the stomach for yet another invasion of one of its socialist neighbors.

Ted Lipien was Voice of America acting associate director in charge of central news programs before his retirement in 2006. In the 1970s, he worked as a broadcaster in the VOA Polish Service and was the service chief and foreign correspondent in the 1980s during Solidarity’s struggle for democracy in Poland.