Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

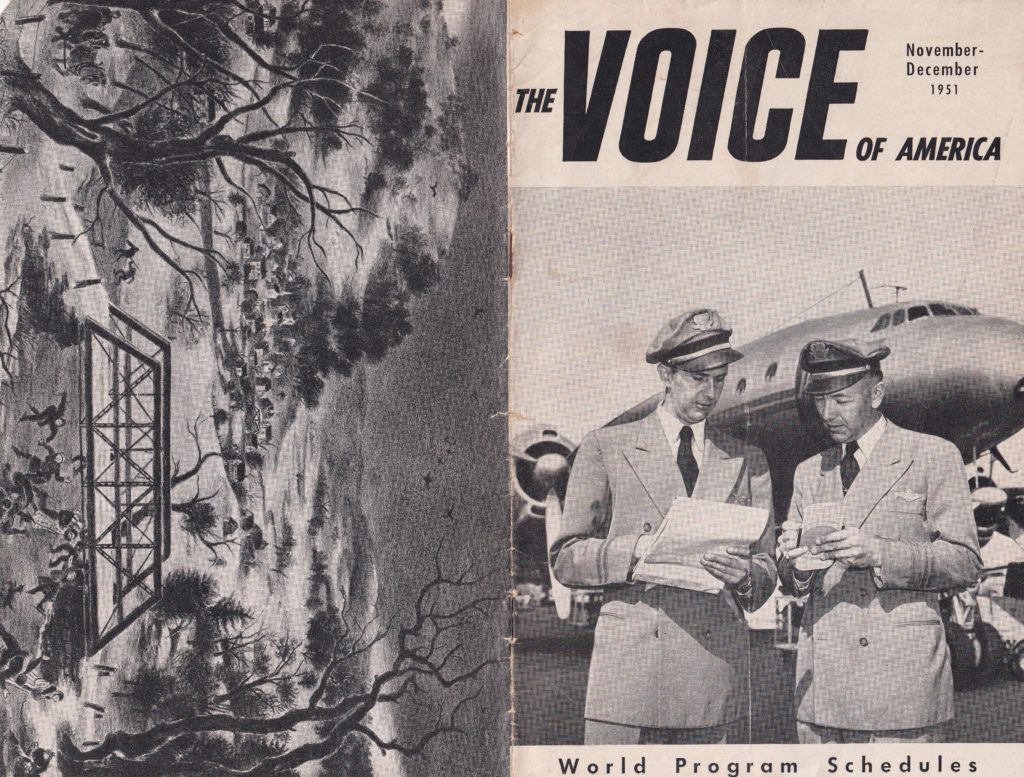

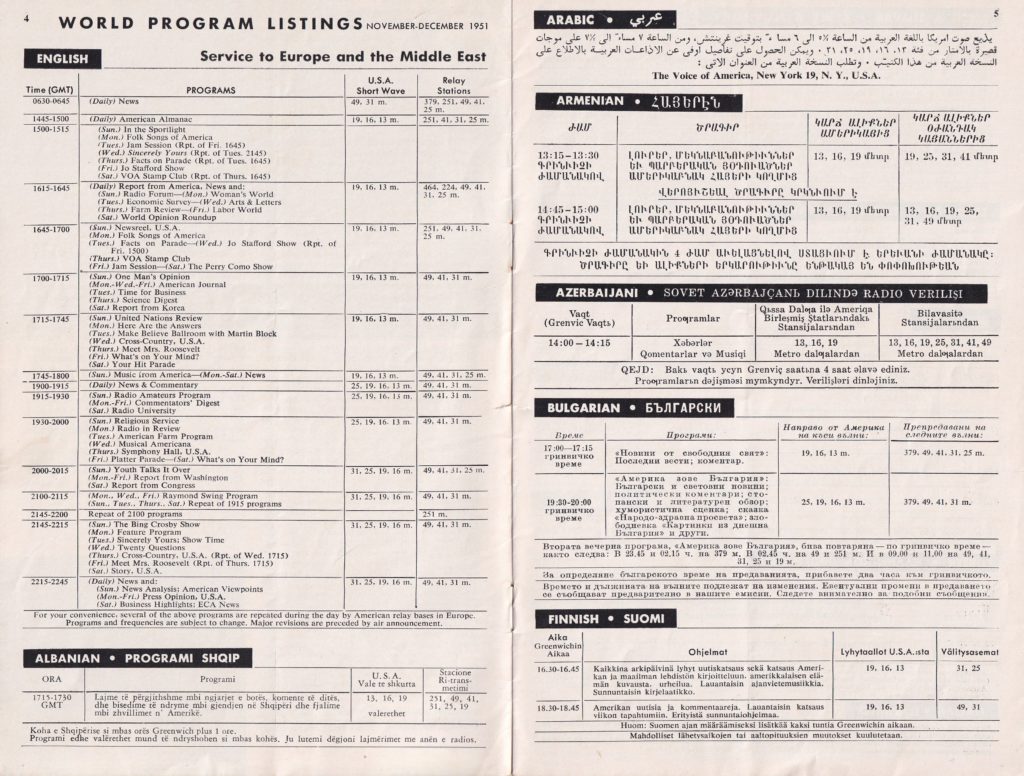

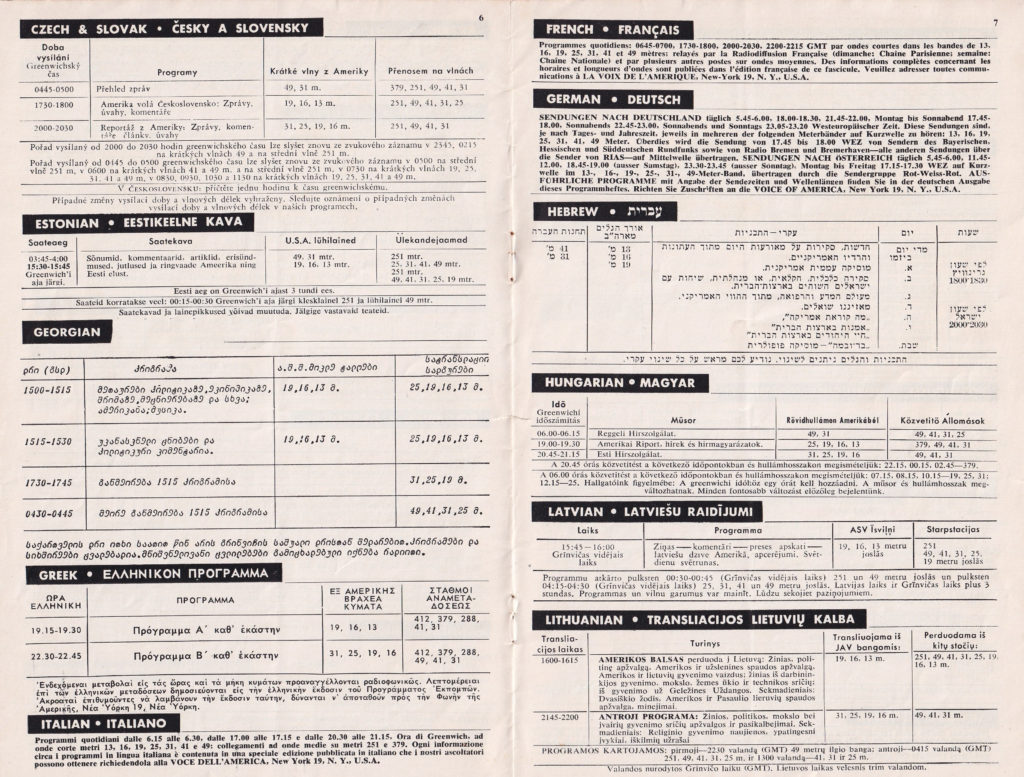

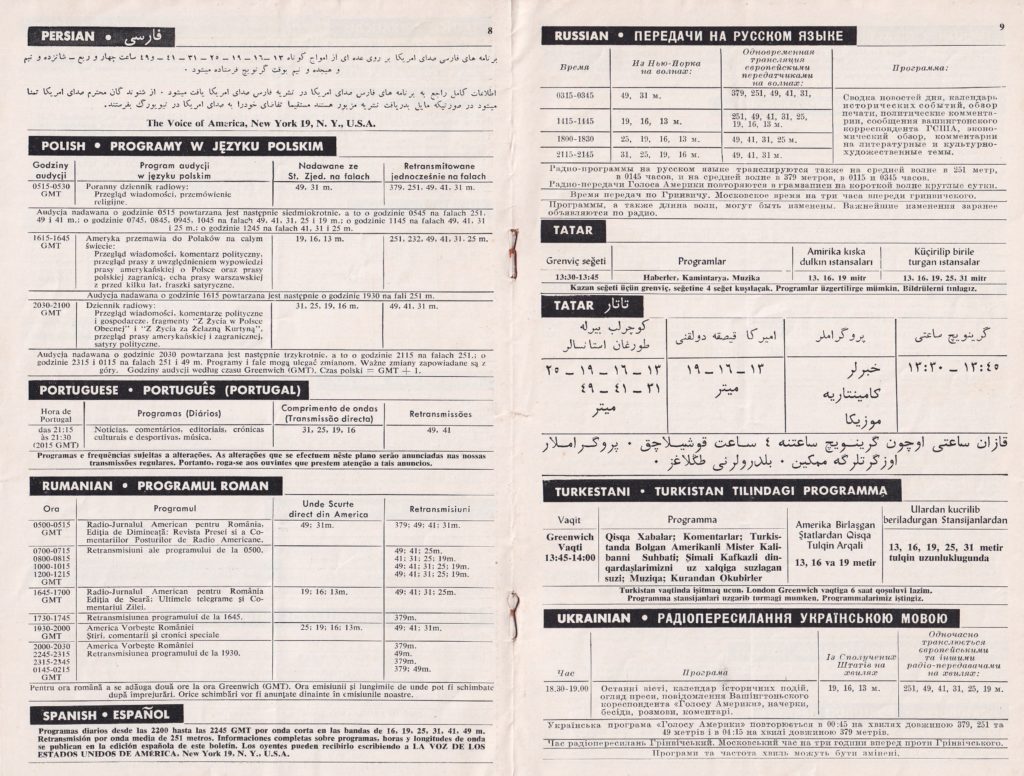

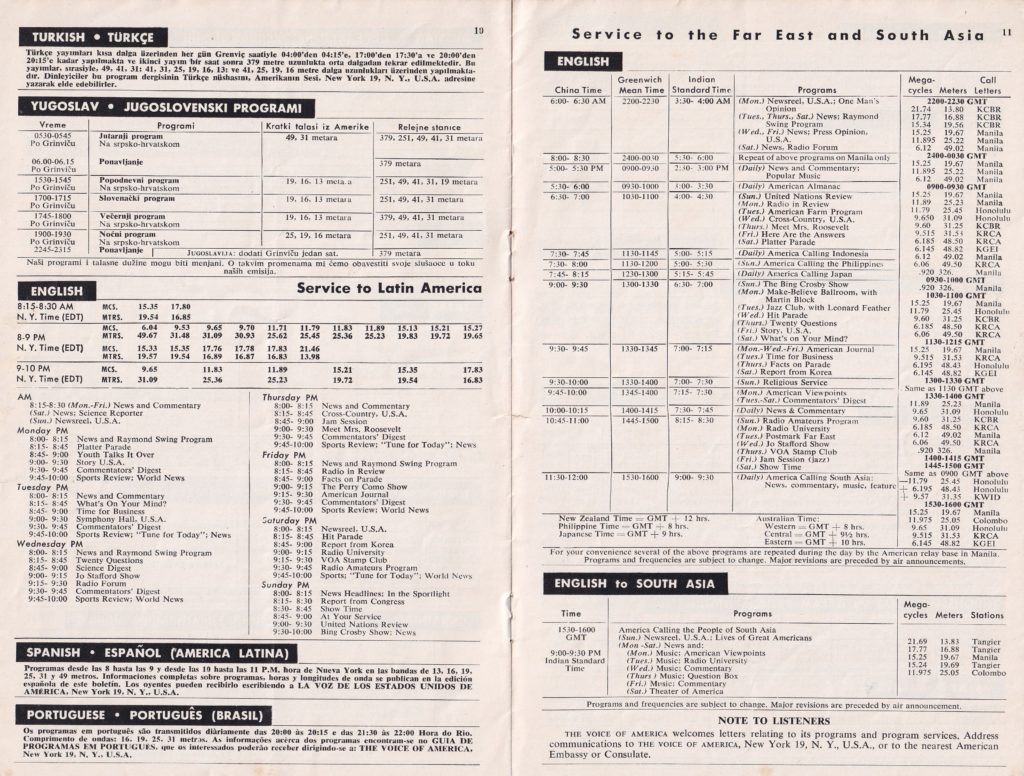

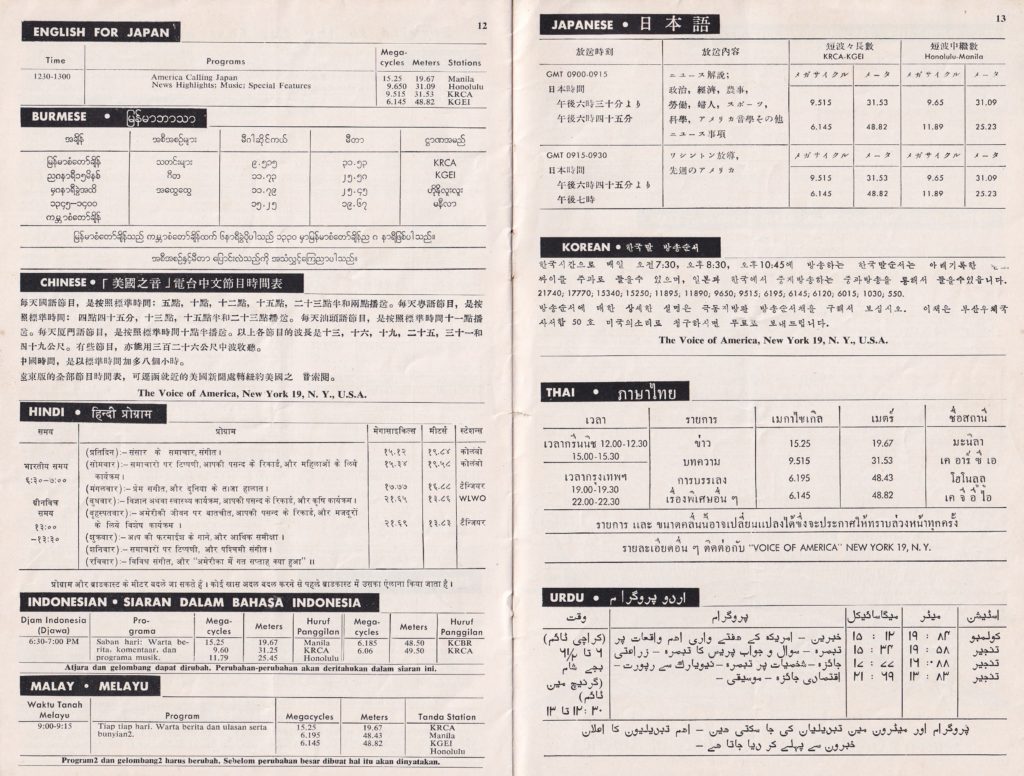

The Voice of America Program Schedule for November-December 1951 reveals a year of program expansion and programming changes at the U.S. government’s radio station for overseas audiences, which was managed by the Department of State diplomats and hired communications experts at that time.1 The original brochure is part of the Cold War Radio Museum collection. It includes full or partial program listings of VOA English and almost all VOA foreign language services broadcasting at the end of the year in 1951. Some of the new VOA foreign language broadcasts launched that year would be later eliminated or reduced to feed services, while others would continue until the end of the Cold War. A few VOA language services established in 1951 are still broadcasting today.

The primary reason for the expansion of VOA broadcasts in 1951 was the start of the Korean War on June 25, 1950, with the North Korean attack on South Korea. The North Korean invasion was instigated and supported by the Soviet Union, whose totalitarian leader Joseph Stalin had already broken the promises to U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill given at the Yalta Conference in 1945 to allow free elections and democracy in East-Central Europe after the war.

Even before the Korean War, the Truman administration secretly supported the creation of Radio Free Europe (RFE) to launch radio broadcasts to the so-called captive nations. RFE was described in official press releases as an initiative independent from the U.S. government and supported by donations from individual Americans and private institutions and businesses. However, the station was, in fact, secretly funded and managed by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)—an arrangement that lasted until the early 1970s. Because the U.S. government’s involvement and funding for Radio Free Europe were kept secret, and RFE was presented as a private initiative, President Truman and his administration never received full credit for creating a highly effective institution for countering censorship behind the Iron Curtain. On January 27, 1948, President Truman signed into law the bipartisan U.S. Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 (Public Law 80-402), popularly called the Smith–Mundt Act. The bill authorized the State Department’s and Voice of America’s informational activities abroad while banning the distribution of VOA programs in the United States and imposing much stricter security clearance requirements for VOA personnel.

However, Truman administration officials did not believe the Voice of America alone, as a U.S. government entity within the State Department, would be capable of breaking through the censorship barrier with hard-hitting programs and proceeded with plans to establish Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. Still, the administration wanted VOA to respond more vigorously with new and more focused programs to the start of the Korean War and the threat of Soviet propaganda and potential aggression in other parts of the world, including the Middle East. In a foreign policy speech on April 20, 1950, to American Society of Newspaper Editors members, President Truman unveiled the “Campaign of Truth”– a multi-faceted U.S. government’s international information response to harsh Soviet propaganda attacks on the United States and its allies.2

As one part of this effort, VOA programs in Hebrew went on air for the first time on April 15, 1951. It turned out, however, to be a short-lived undertaking. The Eisenhower administration ended VOA Hebrew broadcasts on May 23, 1953, for reasons still not fully explored. Some State Department officials claimed these programs could not attract any measurable audience in Israel.

But the announcement of plans to close down the VOA Hebrew Service during the intensifying anti-Semitic campaigns in the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia resulted in criticism within VOA and in the U.S. Congress. Critics accused the Voice of America’s management in the State Department of being soft on communism and unwilling to confront human rights violations in countries ruled by repressive regimes with which the United States maintained diplomatic relations.

Several other VOA language services on the air in 1951 would also be terminated in the following years because of the lack of effectiveness combined with declining audiences, changing priorities of U.S. foreign policy, and the establishment of Radio Free Europe and later Radio Liberty (RL), which was initially called Radio Liberation.

REF and RL had better area experts, better managers, more funding, more airtime, and, unlike VOA, did not broadcast in English. VOA English broadcasts, both then and now, had minimal audiences except for a few English-speaking countries in Africa, but VOA managers preferred to protect English-language programs from cuts and preserve federal government jobs they could offer to their American associates in private media. When budget cuts were required, the American management’s first targets were always VOA foreign language services.

At Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, CIA-trained American managers allowed their foreign-born broadcasters much more editorial independence than U.S. diplomats and American media executives running the Voice of America. One reason for maintaining the pretense of RFE’s and RL’s independence from the U.S. government was to permit these stations to be much more direct than the Voice of America in their criticism of the Soviet Union and other communist regimes. VOA was the official station of the United States, but the State Department would claim that Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty did not speak for the U.S. government.

The need for some VOA services outside of the Soviet Bloc was rapidly diminishing in the late 1940s and the early 1950s as local free media outlets became the primary news sources. That was not the case in Eastern Europe, but by the early 1950s, VOA had lost much of its audience in Western Europe, where VOA’s audience was never large to begin with. VOA could not compete effectively with Britain’s BBC, especially as a provider of news in English.

VOA was not doing much better in some of the countries in Asia which had a free press. However, VOA Japanese broadcasts, which were abolished in October 1946, were reinstated in September 1951 due to the Korean War. They originally started out in San Francisco in early 1942 after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Voice of America radio programs to Japan were eliminated for the second time in November 1962. The 1951 program schedule, in addition to the VOA Japanese-language broadcasts, also lists separate VOA English programs prepared especially for radio listeners in Japan.

Broadcasting in the languages spoken in the Soviet Union became a priority for the Truman administration. One of the lesser-known initiatives during that period was the creation of the VOA Tatar Service, which started broadcasting on June 24, 1951. Tatars living in the Soviet Union needed uncensored news in their own language, but after Radio Liberty was established, it took over broadcasting in Tatar. Radio Liberty, based at that time in Munich, West Germany, started broadcasting in Tatar-Bashkir and Turkmen in 1953. The VOA Tatar Service was closed down in 1953. The VOA Turkestani Service, broadcasting to the Soviet Union in 1951, was also soon abolished.

RL’s greater expertise in the various nationalities in the Soviet Union and the proximity to the target area were likely the main reasons for eliminating these two VOA services. Radio Free Europe services to Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania were established in 1950, but VOA broadcasts to these countries continued. Most of RFE’s East-Central European services would soon gain much larger audiences than the VOA audiences in the same countries, especially in Poland.

Several VOA services still broadcasting to Western Europe in 1951 would stay in operation for only a few more years due to declining interest and shrinking audiences. VOA broadcasts in Finnish, which started on April 16, 1942, were canceled on September 13, 1953. The VOA Spanish Service broadcasting to Spain was abolished in 1955. The VOA Italian Service closed down in 1957. Direct broadcasts in German were discontinued in 1960. French broadcasts to Europe were abolished in 1961. VOA could not attract substantial audiences in West European countries with free media or even in countries with partially independent media.

The Voice of America, however, did have measurable audiences in some communist-ruled countries without a free press. President Truman had already initiated programming and management reforms at the Voice of America as part of his “Campaign of Truth” initiative to make VOA programs more effective in opposing communism.3 Nevertheless, VOA was still criticized in 1951 for being “soft” on the Soviet Union.

Speaking on the House of Representatives floor on July 24, 1951, Congressman John V. Beamer (Republican – Indiana) said that the Voice of America was “about as hard-hitting as a creampuff.” He also revealed that VOA had practically no audience in pre-Castro Cuba, where free media existed before the 1952 coup led by General Fulgencio Batista.4 There was also limited press freedom even under the Batista regime. Press freedom in Cuba ended completely with Castro’s communist coup in 1959.

1951 was still the year of growth for the Voice of America. An impressive number of new VOA language services started broadcasting that year. They included VOA Armenian, VOA Azerbaijani, VOA Estonian, VOA Georgian, VOA Hebrew, VOA Hindi, VOA Latvian, VOA Lithuanian, VOA Swatow (Chinese dialect), VOA Tatar, and VOA Urdu. VOA Turkestani Service was most likely also launched in 1951.

Voice of America broadcasts in Russian to the Soviet Union started earlier but were relatively new in 1951. The Russian Service was at that time undergoing a major change from avoiding criticism of the Soviet Union under its first service chief and later VOA director, State Department diplomat Charles Thayer, to becoming strongly anti-Soviet under its new chief, Alexander Gregory Barmine, a former Soviet military intelligence officer with the rank of brigadier general who defected to the West.5

VOA programs in Russian went on air for the first time in February 1947. VOA officials had been reluctant to start them earlier because they feared that U.S. government-sponsored Russian broadcasts would offend Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin during World War II and, in the period immediately after the war, complicate U.S.-Soviet relations.

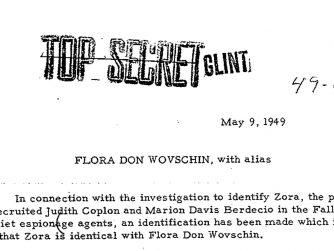

When the United States and the Soviet Union were allies against Nazi Germany, pro-Soviet VOA officials and journalists covered up Stalin’s crimes and repeated Soviet propaganda.6 The first VOA director, John Houseman, was quietly forced to resign by the Roosevelt administration for hiring communist broadcasters, even though President Roosevelt tried to appease Stalin and agree to almost all of his demands for control over East-Central Europe.7

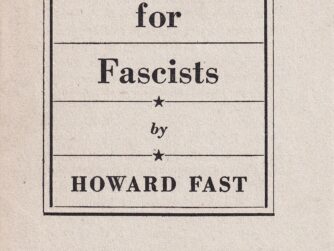

VOA’s first chief English news writer and editor under John Houseman was American Communist Howard Fast. After being also forced to resign from VOA in 1944, Fast, who was a prolific writer of historical fiction, worked for the Communist Party newspaper The Daily Worker, and in 1953 received the Stalin Peace Prize.8 After being targeted by Senator Joseph MacCarthy (Republican – Wisconsin), Fast spent several months in federal prison after being convicted of contempt of Congress for refusing to name members of a communist front organization.

By 1951, the Truman administration replaced pro-communist VOA broadcasters with anti-communist refugee journalists from Eastern Europe and carried out personnel changes in the State Department among officials in charge of Voice of America programs to make them more effective in countering Soviet propaganda. One of the journalists hired in 1948 by the VOA Polish Service was a former anti-Nazi Polish underground resistance member, Zofia Korbońska, who escaped from Poland. Former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane recommended her for a broadcasting job with VOA.9

Meanwhile, some of the anti-American propaganda in Eastern Europe in 1951 was being generated by former VOA journalists, who, after the war, returned to their native countries and served the Soviet-dominated communist regimes. One of the most aggressive anti-U.S. communist propagandists in Poland was a former Voice of America Polish Service editor, Stefan Arski, aka Artur Salman.10

At the Voice of America, still located at that time in New York before the move to Washington in 1954, refugee journalists from Eastern Europe and Russia were given more independence in reporting on human rights abuses in the Soviet Bloc, but as late as the end of 1951, the VOA director (from October 1949 to September 1952), Foy D. Kohler who was a career State Department diplomat, still lashed out against a former Office of War Information (OWI) German editor and internationally-published journalist Julius Epstein for daring to expose the impact of Soviet propaganda on Voice of America broadcasts during World War II and in the period after the war.

Kohler called Epstein, who was laid off from his OWI job in 1945, most likely due to his criticism of the management, “not best type of new American citizen,” and suggested that he should be investigated.11 Foy Kohler was later U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union during the Cuban Missile Crisis and, from 1974 to 1977, member of the Board of International Broadcasting (BIB), which oversaw the management of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.

In The Gulag Archipelago, Soviet dissident writer and Nobel Prize winner Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, whom the Voice of America management censored in the 1970s to prevent complications in the U.S. policy of detente with the Soviet Union, praised Julius Epstein’s investigative reporting—not in connection with VOA, but in Epstein’s book Operation Keelhaul (1973).12 In his book, Epstein revealed another shameful U.S. government secret—the forcible handing over to Stalin of hundreds of thousands of Soviet refugees, many of whom were innocent of collaborating with the Germans and did not want to go back to Russia.

Even though personnel and programming reforms had already begun under the Truman administration, criticism of the Voice of America continued in the U.S. Congress in 1951.

Speaking in the U.S. House of Representatives on July 24, 1951, Congressman Richard B. Wigglesworth (Republican – Massachusetts) delivered a devastating critique of VOA broadcasts to Poland. His criticism was based on letters smuggled from Poland and analyzed for the Voice of America management by Poland’s former wartime ambassador in Washington, Jan Ciechanowski, one of the early critics of Soviet influence within the Office of War Information, where VOA broadcasts originated during the war. Letters smuggled to the United States described VOA programs in 1951 as “uninteresting, drab, bureaucratic in tone, unconvincing.”13

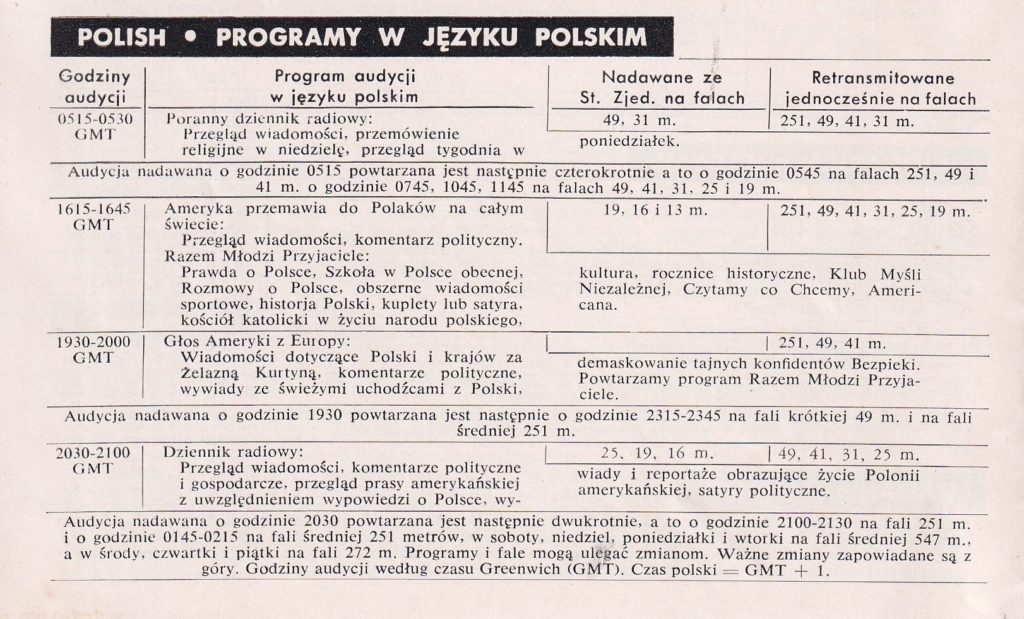

However, the VOA Polish Service program schedule for November-December 1951 already suggests a more hard-hitting approach toward the communist regime in Warsaw than in previous years. One of VOA’s Polish programs in 1951 was titled “Life Behind the Iron Curtain.”

On October 1, 1951, the Polish Service started broadcasting one of its programs from the newly-established VOA European Radio Center in Munich.14 The establishment of the VOA bureau in Munich may have been an effort to compete with Radio Free Europe, also based in Munich, or at least to make VOA programs somewhat more relevant for audiences behind the Iron Curtain.

The bipartisan Madden Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives to investigate the Katyn massacre of thousands of Polish military officers in the Soviet Union was created in 1951 and focused on VOA’s failure to report fully on Soviet and other communist atrocities. There was a significant change in VOA programs to Poland in 1952 after the Madden Committee, named after its chairman, Rep. Ray Madden (Democrat – Indiana), started to reveal the VOA management’s censorship of news about Soviet human rights violations. Truman administration officials allowed for increased criticism of communist regimes in VOA broadcasts, starting in 1951 and continuing in 1952.

In contrast to 1951, the VOA program schedule for September-October 1952 included many more titles suggesting a bolder type of journalism focused on events in communist-ruled Poland. Some of these new programs originated from VOA’s European Radio Center in Munich: “The Truth About Poland,” “Conversations About Poland,” “The Catholic Church in the Life of the Polish Nation,” “Polish History,” “Interviews with New Refugees from Poland,” “The Club of Independent Thought,” “We Read What We Want,” as well as satirical programs.15

The Polish Service of the Voice of America attempted to compete with the Polish Service of Radio Free Europe in delivering news and commentary about Poland but lacked the resources, American managers with adequate knowledge of communist propaganda, and sufficient independence to do its job as effectively as RFE.

One of the new VOA Polish Service programs was titled “Unmasking Secret Informants of the SB.” Bezpieka, or SB, was what the Poles called the communist secret police in Poland.

Ironically, one of the informants and communist spies, Zbigniew Brydak, whose VOA’s radio name was Stefan Michalski, was employed by the Polish Service of VOA’s European Radio Center in Munich before being discovered. He was questioned but was released and managed to escape back to Poland, where he joined another former VOA Polish Service journalist Stefan Arski in producing anti-American propaganda. Brydak also tried to infiltrate Radio Free Europe, but a young escapee employed by RFE who knew Brydak in Poland, Marek Walicki, who in the 1980s was my deputy at the VOA Polish Service, warned the director of RFE Polish Service Jan Nowak Jeziorański that Brydak could not be trusted. Thanks to Marek Walicki, Brydak failed in his effort to secure a job with Radio Free Europe.16

VOA’s European Radio Center in Munich did not remain in operation for long. It was closed down after several years as VOA’s management started once again to promote a more conciliatory approach to programming to communist-ruled nations in support of the policy of detente with the Soviet Union and other communist regimes.

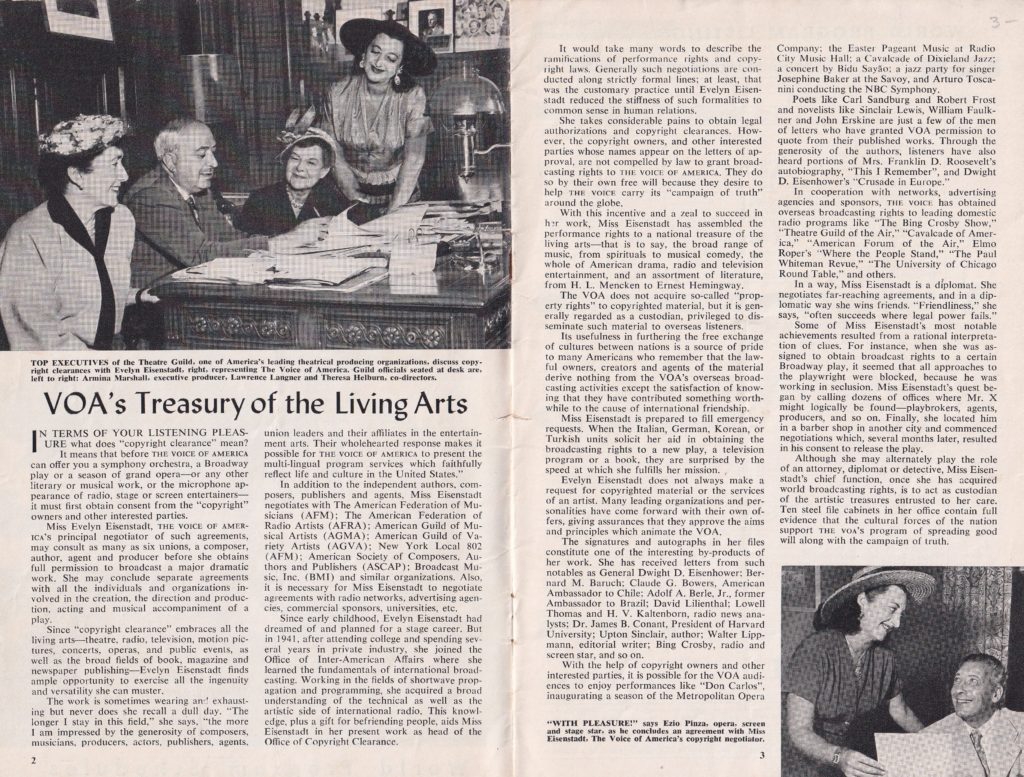

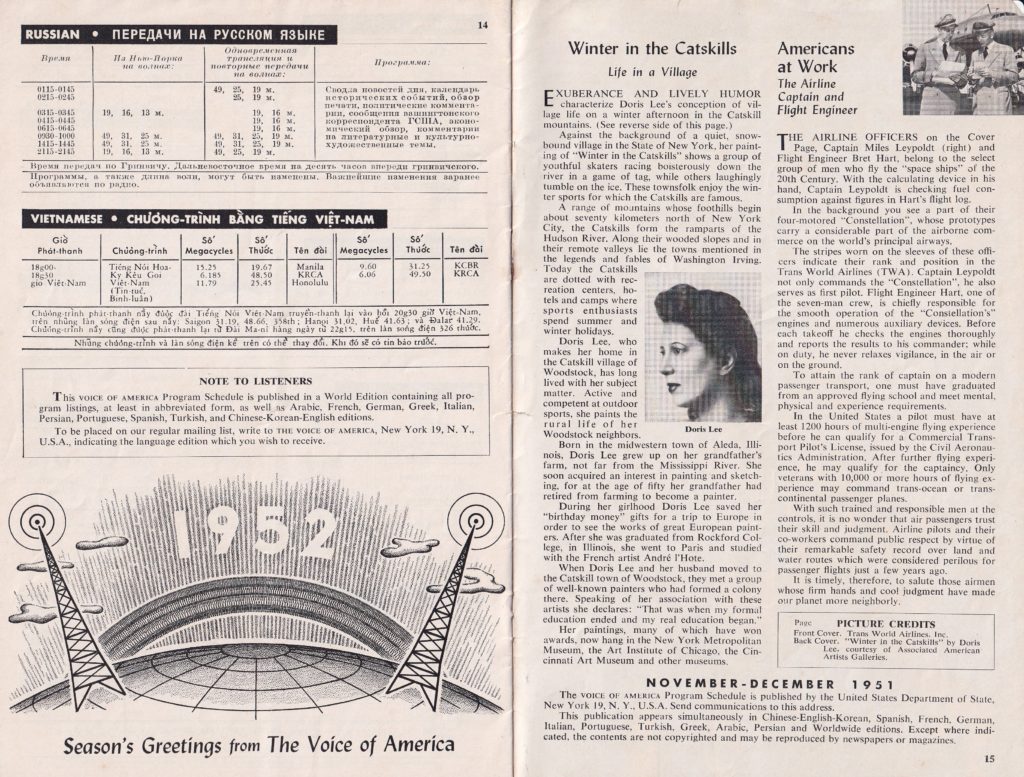

The 1951 Voice of America World Program Schedules brochure also included articles about the work of the VOA Office of Copyright Clearance and its chief negotiator Evelyn Eisenstadt, the art of American painter Doris Lee, and a short feature about Trans World Airlines (TWA).

NOTES:

- The Voice of America, World Program Schedules, November-December 1951. Cold War Radio Museum collection.

- Harry S. Truman, “Address on Foreign Policy at a Luncheon of the American Society of Newspaper Editors,” April 20, 1950. National Archives, Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/public-papers/92/address-foreign-policy-luncheon-american-society-newspaper-editors.

- Ted Lipien, “Truman’s ‘Campaign of Truth’ at Voice of America Part I: Countering Soviet Propaganda Abroad and at Home,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), March 25, 2021, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/campaign-of-truth-at-voice-of-america-part-i/.

- Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Had No Audience in Pre-Castro Cuba and Initially Supported Soviet Socialism in Eastern Europe,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), February 24, 2020, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-had-no-audience-in-pre-castro-cuba-did-poorly-in-exposing-failures-of-soviet-socialism/.

- Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Russian Branch Chief Alexander Barmine Was An Ex-Soviet General and Ex-Spy Who Testified Before Senator McCarthy – Page 9 – Ending Censorship of Katyn Massacre,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), April 17, 2023, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-russian-branch-chief-alexander-barmine-was-an-ex-soviet-general-and-ex-spy-who-testified-before-senator-mccarthy/.

- Curator, “Sumner Welles Warns White House About First Voice Of America Director Hiring Communists – Cold War Radio Museum,” accessed January 22, 2023, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/timeline/sumner-welles-warns-white-house-about-first-voice-of-america-director/.

- Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director Was a Pro-Soviet Communist Sympathizer, State Dept. Warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), May 5, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/.

- Curator, “Communist Writer And Future Stalin Peace Prize Winner Howard Fast Resigns From Voice of America – Cold War Radio Museum,” accessed January 22, 2023, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/timeline/communist-writer-and-future-stalin-peace-prize-winner-howard-fast-resigns-from-voice-of-america/.

- Ted Lipien, “LIPIEN: Remembering a Polish-American Patriot,” The Washington Times, accessed May 13, 2023, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2010/sep/1/remembering-a-polish-american-patriot/.

- Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Polish Writer Listed As His Job Reference Stalin’s KGB Agent of Influence Who Duped President Roosevelt,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), February 12, 2020, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-polish-editor-listed-stalins-kgb-agent-of-influence-as-job-reference/.

- Curator, “Quote: ‘…the Time Has Arrived to Investigate Mr. Epstein…he Is Not…best Type of New American Citizen’ – VOA Director Foy D. Kohler – Cold War Radio Museum,” accessed June 21, 2023, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/timeline/quote-the-time-has-arrived-to-investigate-mr-epstein-he-is-not-best-type-of-new-america-citizen-voa-director-foy-d-kohler/.

- Aleksandr Isaevich Solzhenit︠s︡yn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, 1st ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1974), p. 85.

- Curator, “Congressman Reveals Voice Of America To Behind Iron Curtain Is ‘Drab’ And ‘Unconvincing’ – Cold War Radio Museum,” accessed October 31, 2022, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/timeline/congressman-reveals-voice-of-america-to-behind-iron-curtain-is-drab-and-unconvincing/.

- The Office of US High Commissioner for Germany, “VOA Broadcasts in Russian From Munich,” Information Bulletin, June 1952, p. 18.

- The Voice of America, World Program Schedules, September-October 1952, p. 8. Cold War Radio Museum collection.

- Marek Walicki, Z Polski Ludowej do Wolnej Europy (Warszawa: Bellona, 2018), pp. 170-182.