Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

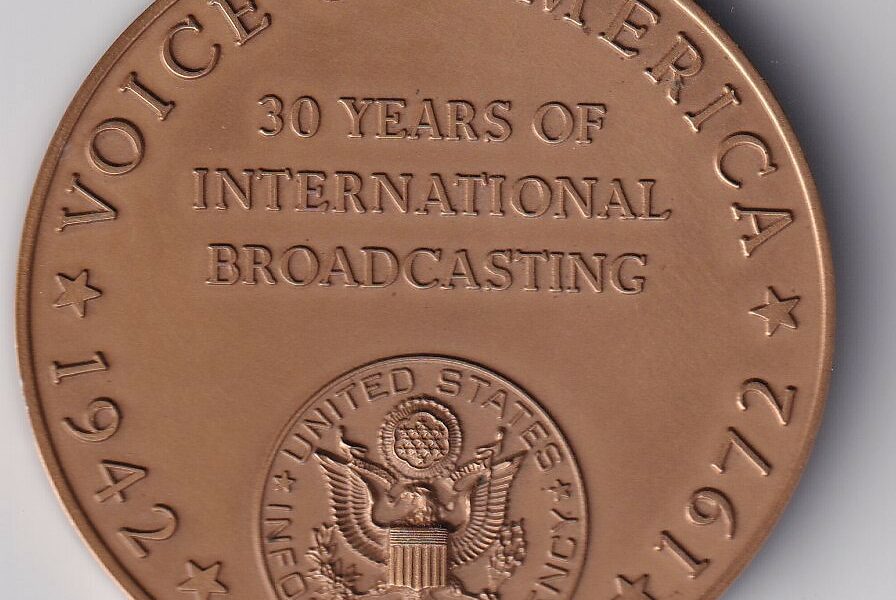

In February 1972, the U.S. government-funded and managed Voice of America (VOA), then part of the United States Information Agency (USIA), observed the 30th anniversary of its founding in 1942, during World War II. The Voice of America commissioned a bronze medal to mark 30 years of VOA’s international broadcasting. When I joined the VOA Polish Service in December 1973 in the period of détente in relations with the Soviet Union during the Nixon-Ford administrations, Radio Free Europe (RFE) was well ahead of VOA in the number of radio listeners in Poland (RFE’s audience was about five times larger than VOA’s) and remained in the lead for many years.1 VOA journalists in the foreign language services were reduced to being mostly translators of centrally produced English-language programs with limited relevance for the countries ruled by communist regimes. VOA caught up with RFE in the number of listeners in Poland only during the Reagan administration when restrictions on in-depth reporting by foreign language services and previously disallowed criticism of the Soviet Union and communism were lifted in the 1980s.

There are three sets of the Voice of America’s history: 1. the highly hagiographic official version; 2. books and articles by some former U.S.-born VOA officials and journalists presenting not much less sugared version of the station’s history, with many controversial topics played down or omitted; 3. a very small number of memoirs of refugee VOA journalists, many of them from nations under communist rule, with more truthful accounts of the station’s achievements and failures.

The 1970s were the period of some of the greatest frustrations for the VOA Polish Service broadcasters, and the 1980s were, for us professionally, most rewarding when we knew we had the maximum impact in Poland. The 1950s, which included the last two years of the Truman administration and the eight years of the Eisenhower administration, were another decade when the Voice of America had a greater impact in the countries behind the Iron Curtain. In 1957, the station celebrated its 15th anniversary, but by then the USIA management and central English-language newsroom and other producers of programs to be translated by the foreign language services already began to soften VOA broadcasts to comply with their pro-detente ideological outlook and the needs of U.S. diplomacy toward the Soviet Union and other communist regimes.

Foreign-born journalists noted the malaise at the Voice of America in the 1970s and in other periods. My former deputy in the Polish Service in the 1980s, Marek Walicki, who had joined VOA in 1976 after working for Radio Free Europe in Munich and New York, wrote in his memoir, Z Polski Ludowej do Wolnej Europy, republished in Poland in an expanded edition in 2023, ” from the start, my work at the Voice of America seemed to me like a child’s play compared to our hard and independent work in Radio Free Europe.”2

I was given to translate one of the news reports in English sent in by Voice of America correspondents positioned around the world, returned the translation for approval to one of the five editors, and went for a walk on the National Mall between Constitution and Independence Avenues, where our offices and studios were located. After that, I read a little bit, had time for lunch, and in the afternoon, received something else for translation. This was repeated day after day.3

Marek Walicki added that after a while, he was given to record scripts poorly translated by others and almost unedited, which led to his first conflict with his superiors.4

From the very beginning of the Voice of America and continuing through the 1970s, the management of the VOA central English-language services restricted access of foreign language broadcasters to wire service reports and made them rely on the in-house-produced, often spotty and inadequate news reporting about the Soviet Union and later about the Soviet Bloc countries. This has always been the preferred arrangement of the American management at the Voice of America and its federal agency because it allowed for the hiring of a large number of American-born journalists, managers, and contractors despite the fact that English-language programs had practically no audience in communist-ruled countries.

Refugee journalists’ status and their ability to do original reporting greatly improved only after Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980. For much of the 1980s, I was in charge of the VOA Polish Service. By the end of the 1980s, we nearly caught up with RFE’s Polish Service in audience reach in Poland.

However, the malaise had returned at the Voice of America after the end of the Cold War. Mine and Marek Walicki’s successor in charge of the Polish Service, a well-known and talented Polish journalist Maciej Wierzyński, who, before joining VOA, worked for Radio Free Europe, made these observations about the Voice of America of the 1990s.

For the next six years, I worked for the Voice of America, and I consider this period the most frustrating in my life. The Voice of America was an [government] office (urząd), where one worked from 9 to 5. We did not have very intelligent bosses, whose main concern was to keep their jobs, in the period when American international broadcasting was getting less and less money and Voice of America language services were being liquidated one after another. The bosses neither appreciated nor understood our work.5

Prior to the successful broadcasting to the Soviet Bloc countries in the 1980s during the Reagan administration, the Voice of America also enjoyed a period of enhanced effectiveness in countering communist propaganda during the last years of the Truman administration, and for some period of time, during the Eisenhower administration.

On February 25, 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower visited the Voice of America headquarters in Washington, DC, and made a special shortwave broadcast to commemorate VOA’s 15th anniversary. His speech was partly focused on the situation in the Middle East. United Press reported about President Eisenhower’s speech at the Voice of America:

He warned the people of the Middle East to stand clear of “the menace of international Communism” lest it “smash all their hard-won accomplishments overnight.”

United Press on President Eisenhower’s Voice of America speech on February 25, 1957 to mark VOA’s 15th anniversary.

As U.S. president, Eisenhower was unhappy about the management of the Voice of America. In his military leadership role in World War II, he also found some VOA programs counterproductive. After leaving the White House in 1961, he condemned a biased Voice of America reporter who sought to create news to embarrass the administration rather than report objectively and with balance on criticism of U.S. policy. The VOA reporter allegedly tried to get a U.S. senator to criticize President Eisenhower’s decision to send U.S. troops to Lebanon. The senator refused the request and publicized the incident.

General Eisenhower, who was the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe during World War II, also alluded briefly in his 1965 memoirs Waging Peace to VOA’s wartime record of using Soviet propaganda at the expense of American interests. Eisenhower had a simple advice for VOA: “The Voice of America should … employ truth as a weapon in support of Free World.”

In Washington I had been told that a representative of the Voice of America (our governmental radio overseas) had tried to obtain from a senator a statement opposing our landing of troops in Lebanon. In a state of some pique I informed Secretary Dulles that this was carrying the policy of “free broadcasting” too far. The Voice of America should, I said, employ truth as a weapon in support of Free World, but it had no mandate or license to seek evidence of lack of domestic support of America’s foreign policies and actions.

[Footnote in Waging Peace by Dwight D. Eisenhower] During World War II the Office of War Information had, on two occasions in foreign broadcasts, opposed actions of President Roosevelt; it ridiculed the temporary arrangement with Admiral Darlan in North Africa and that with Marshal Badoglio in Italy. President Roosevelt took prompt action to stop such insubordination.6

President Eisenhower was right. In both cases during World War II and to a much lesser extent, even briefly during his administration, some biased VOA officials, editors, and reporters sought to create and influence news and U.S. policy through their own commentary and trying to manipulate news to conform with their ideological bias rather than merely reporting on world events.

During World War II, General Eisenhower and the Army Intelligence had legitimate concerns that some VOA broadcasters following closely the communist and pro-Soviet line could endanger the lives of American soldiers. The State Department shared some of the same concerns with regard to U.S. diplomacy. President Roosevelt’s close friend and advisor, Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, wrote a secret memo to the White House recommending that some of the more extreme Soviet and communist sympathizers in the Office of War Information (OWI) be removed.

They included John Houseman, who was later described as the first director of the Voice of America and falsely hailed by some as a defender of objective and truthful journalism. The Voice of America was promoting of the greatest Soviet propaganda lies under his watch, although other fellow travelers rather than Houseman, who was mostly in charge of radio production, were responsible for program content. The Office of War Information official issuing propaganda directives to VOA journalists and broadcasters was President Roosevelt’s speechwriter, American playwright Robert E. Sherwood. He was assisted by a former international newspaper reporter, Joseph F. Barnes.

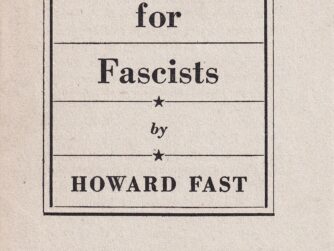

The chief VOA news writer and editor at that time was Communist Party USA activist, American novelist Howard Fast, who in 1953 received the Stalin International Peace Prize. Other Office of War Information officials, propagandists, and journalists who contributed to spreading Soviet propaganda in OWI materials domestically and VOA broadcasts abroad included Elmer Davis, Owen Lattimore, Wallace Carroll, and Nelson Poynter.7

Soviet Russia’s lie that Hitler and Nazi Germans and not Stalin and Soviet Communists were responsible for the mass execution murder of over 20,000 Polish officers, intellectual leaders, and other prisoners of war in the Katyn Forest massacre was the greatest fake news of the World War II and the Cold War period, which the Voice of America under its agency head Elmer Davis and other early pro-Soviet officials helped to spread, starting in April and May 1943.8

Many, probably the vast majority, of the early VOA officials and journalists were ideological and professional followers of the New York Times Moscow fellow traveler correspondent Walter Duranty, who, in 1932, won the Pulitzer Prize for his journalism despite deliberately lying in his reporting from the Soviet Union. Later, Duranty also lied about the Holodomor, the forced starvation of peasants in Ukraine. The communist-made famine took millions of lives. The early Voice of America program director, Joseph Barnes, and Walter Duranty were close friends when both of them reported from Moscow in the 1930s.9

Since Duranty received his journalistic award in 1932, which the 2002-2003 Pulitzer Prize Board—whose membership reads like Who’s Who in journalism, media industry, U.S. government service, NGOs, and academia—refused to revoke, many communist and post-communist regimes and terrorist groups could claim the mantle of human rights and anti-imperialism to excuse or hide their contempt for human life and their genocidal crimes.10

This propaganda has duped many Voice of America and other Western journalists over the years, especially in the 1940s, and again since the end of the Cold War. As I noted in one of my recent op-eds in The Hill, a major part of the problem seems to be that Soviet communist atrocities, unlike those of the Nazis in Germany, were never put on trial or punished.11

Supported by the U.S. Army intelligence branch, the State Department refused to give John Houseman a U.S. passport to travel aboard as a U.S. government representative.12 Fast’s application for a U.S. passport to travel to the Middle East as a Voice of America U.S. government representative was also refused, and he resigned from VOA in 1944.

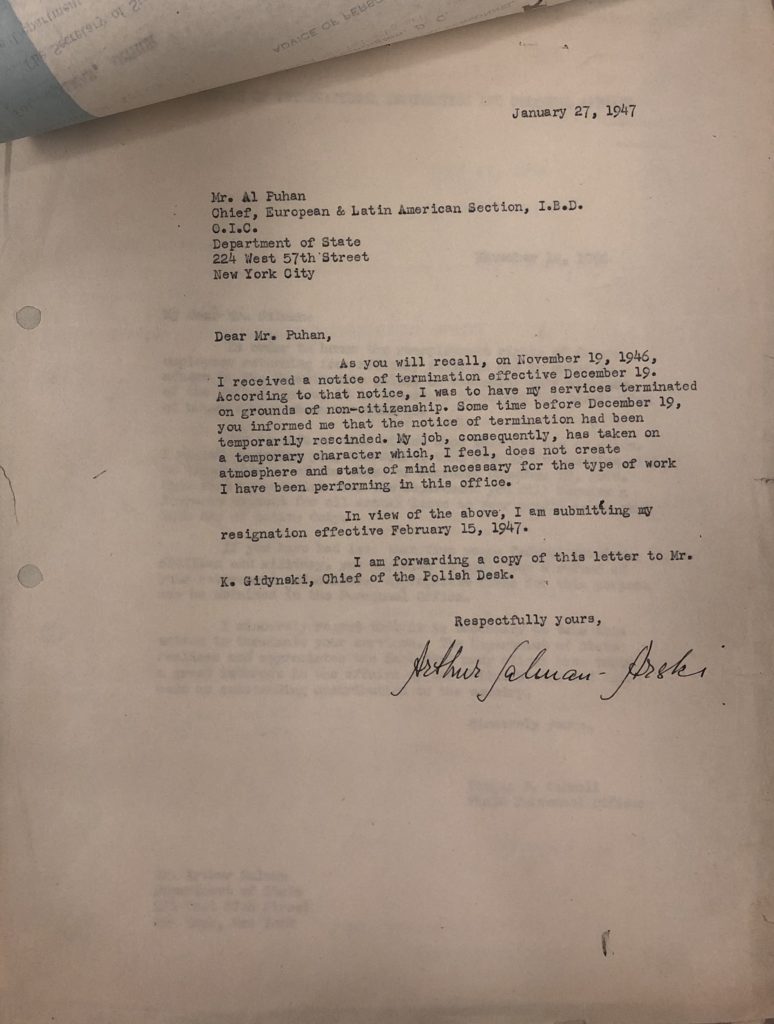

Accused of hiring Communists, Houseman and a few other propaganda agency officials were forced to resign in 1943 and 1944, but many others stayed on and continued with pro-Soviet propaganda at the Voice of America for several more years. The Truman administration forced most of the remaining officials and journalists who refused to criticize the Soviet Union to resign by the early 1950s. A few former VOA journalists ended up working for communist regimes. The chief anti-U.S. communist propagandist in Poland in the 1950s was a former VOA editor Stefan Arski (his real name was Artur Salman).13

The former VOA Czechoslovak Service chief, Adolf Hoffmeister, became the Stalinist regime’s ambassador to France.14

After repeating Soviet propaganda and covering up Stalin’s crimes during the first several years since Voice of America’s founding in 1942, VOA broadcasts, especially in Russian and other Central and East European languages, refocused in the last years of the Truman administration and the first years of the Eisenhower administration on exposing violations of human rights in communist-ruled nations thanks to new program managers and newly hired journalists who were refugees from communism.15 They included the legendary anti-Nazi Polish resistance member and wartime radio coder, Zofia Korbońska, who joined the Voice of America in 1948 at the recommendation of former U.S. Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane.16

In 1951, the Truman administration established the VOA Munich Center, a relatively new and small scale project to show that the United States government was serious about reforming its international broadcasting and countering communist propaganda. After several years of ignoring repressions and human rights violations in the Soviet Union and in East-Central Europe, by 1952 the new policy of the Voice of America management in the US State Department was to establish presence closer to the target area to be able to provide more local news and commentary with the help of refugee journalists and escapees from the Soviet Block countries. The first VOA broadcast from Munich was in Polish on October 1, 1951. In moving a small part of its operations to Munich, VOA was duplicating to a limited degree the highly desired and successful RFE model of surrogate broadcasting consisting of using first-hand sources of information from the target countries.17

However, toward the end of the Eisenhower administration, VOA, at that time under the control of the United States Information Agency, again started to censor sharp criticism of the Soviet Union and other communist regimes. This censorship was not nearly as severe as during the World War II period, when VOA operated independently while also receiving directives from the Roosevelt White House, or when it was managed directly by State Department diplomats from 1945 to 1953. Foreign language broadcasts originating from the Voice of America Munich Radio Program Center were discontinued in 1958 after VOA’s management decided that they were too sympathetic to the plight of refugees from communism and too strident.18 The communist regime in Poland considered Voice of America broadcasts from Munich dangerous enough to send a spy who managed to get a job with the Polish desk but was discovered and fired.

The spy, Zbigniew Brydak, whose radio name was Stefan Michalski, also tried to get a job with the Polish Service of Radio Free Europe. Marek Walicki, who knew Brydak in Poland, warned Jan Nowak Jeziorański, who was in charge of RFE Polish broadcasts, that Brydak cannot be trusted.19 RFE did not hire Brydak. He returned to Poland and recorded broadcasts for the communist shortwave radio station KRAJ, targeting Polish audiences abroad, in which he attacked the Polish staff of the VOA Munich Center and RFE’s Polish Service. He also wrote articles for the weekly news magazine Świat (World), which at that time was under the control of Stefan Arski (Artur Salman), a former VOA Polish Service editor in New York who had returned to Poland in 1947 and joined the Communist Party.20 Walicki also pointed out that Brydak had admitted to the American investigators that he had a role as a provocateur in recruiting young Polish boy scouts to create a fake anti-communist group and then denounced them to the communist security service.21 Marek Walicki wrote that many of the boy scouts, whom the communists arrested after they were identified by Brydak, were executed. Others spent many years in communist prisons.22

Still, a large group of Voice of America journalists (14 senior journalists joined later, as reported in the Washington Post, by 27 others), stated in full confidence in 2020 that “just as was the case with the McCarthy ‘Red Scare,’ which targeted VOA and other government organizations in the mid-1950s, there has not been a single demonstrable case of any individual working for VOA — as the USAGM CEO puts it — ‘posing as a spy.’ ”23 These VOA journalists apparently have never heard of Zbigniew Brydak or other spies and Soviet agents of influence who were VOA journalists or agency officials in charge of VOA.

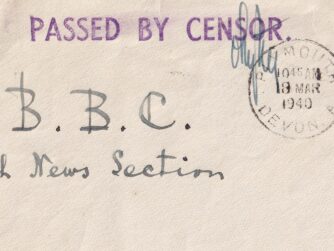

As a Professor of History at Emory University, Harvey Klehr, and a Library of Congress historian, John Earl Haynes, showed in their book, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America (Yale University Press, 2000), secret Soviet intelligence messages monitored by the U.S. counterintelligence services as part of the Venona project contained “the unidentified cover names of several Soviet espionage contacts in the Office of War Information,” including one in the OWI French section.24 The Office of War Information was the wartime government agency in charge of the Voice of America language services and broadcasts from 1942 to 1945. They were part of the OWI’s Overseas Operations Branch in New York City.

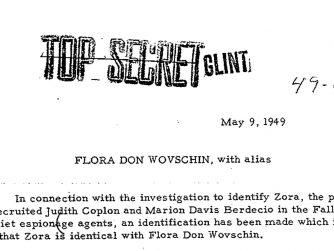

The Venona cables show that the KGB used an agent, codename “Philosopher” (OWI French section), for “providing background information and character appraisals – of OWI personnel.”The Venona project also revealed Flora Don Wovschin (codename “ZORA”), born in 1923 in the United States to Russian immigrant parents, as the most active Soviet agent in the Office of War Information, where she worked in New York as a research assistant and librarian during World War II in the Overseas Branch producing Voice of America broadcasts.

The coverage of human rights violations behind the Iron Curtain by VOA’s central English news service and foreign language desks became further restricted in the 1970s during the Nixon and Ford administrations and improved only slightly under President Carter. Protecting U.S. diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union by VOA, after it was placed in 1953 under USIA, did not fully stop until Reagan administration officials carried out personnel and programming reforms in the early 1980s.

It took a long time for the Voice of America to eliminate pro-Soviet propaganda and pro-Soviet censorship after it had become institutional policy under the pro-Soviet officials and staff during World War II when the United States and Soviet Russia were allies in the war against Nazi Germany. In 1950, the Voice of America management censored a program on the Soviet Katyn massacre by a Polish military officer, prominent writer, artist, and Soviet prison camps survivor Józef Czapski.25 We interviewed Czapski in the 1980s (he was never censored by Radio Free Europe and often participated in RFE broadcasts).26

In the 1970s, the USIA and VOA management banned the Russian Nobel Prize-winning dissident writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn from being interviewed by the Russian Service. The service chief, Victor Franzusoff, wrote in his book, Talking to The Russians, that after the Soviet government had expelled Solzhenitsyn from Russia and stripped him of his Soviet citizenship in 1974, VOA’s Russian Service correspondent in Munich, West Germany, Eugene Nikiforov, asked the author for an interview, and Solzhenitsyn agreed. Franzusoff, who had recently been promoted to be the chief of the Russian Service, described how he was elated by the prospect of a VOA interview with the famous Russian dissident writer. But to his enormous disappointment, the VOA management ordered him to stop his correspondent from conducting the interview.

Franzusoff explained that during the last months of the Nixon administration, he was told the State Department had made the decision that “until further notice, VOA should have nothing to do with the dissident writer.” Whether such a decision had originated in the State Department rather than being taken jointly by officials in charge of the United States Information Agency (USIA) and the Voice of America is not clear. Franzusoff commented, “this decision made no sense to me, of course, but my hands were tied.27

As described in some detail in Mark G. Pomar’s excellent book, Cold War Radio: The Russian Broadcasts of the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, the VOA Russian Service was able to interview Solzhenitsyn in the 1980s and to get him to record extensive excerpts from his books.28 Communism in East Central Europe was peacefully defeated, starting in Poland in 1989. Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty never banned Solzhenitsyn or censored his writings.

NOTES:

- R. Eugene Parta, (Former) Director of Audience Research and Program Evaluation, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Inc., “Listening to Western Radio Stations in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria: 1962-1988 – Longitudinal Listening Trend Charts.” Prepared for the Conference on Cold War Broadcasting Impact co-organized by the Cold War International History Project Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington, DC, and the Hoover Institution of Stanford University, Stanford, California, October 13-15, 2004.

- Marek Walicki, Z Polski Ludowej Do Wolnej Europy, Wydanie I, Świadkowie Historii (Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Ossolineum, 2023), p. 154.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Maciej Wierzyński, “Druga połowa życia,” in Wiesława Piątkowska-Stepaniak, ed., Autroportret zbiorowy – wspomnienia dziennikarzy polskich na emigracji z lat 1945-2002 (Opole: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Opolskiego, 2003), p. 178.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965), p. 279.

- Ted Lipien, “1951 – New York Times Reviews Former Communist Elinor Lipper’s Book Debunking U.S. Office of War Information’s Soviet Propaganda,” Cold War Radio Museum, accessed August 12, 2023, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/new-york-times-reviews-former-communist-elinor-lippers-book-debunking-u-s-office-of-war-informations-soviet-propaganda/.

- “OWI Head Elmer Davis Spread Soviet Katyn Propaganda Lie in World War II Voice of America Broadcasts,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), May 11, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/owi-head-elmer-davis-promotes-soviet-katyn-propaganda-lie-in-the-us-and-in-voice-of-america-radio-broadcasts/.

- S. J. Taylor, Stalin’s Apologist: Walter Duranty, The New York Times’s Man in Moscow (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 280. Waler Duranty to John Gunther, 2 March 1939, Personal Files of John Gunther.

- Pulitzer Prize Board, “Statement on Walter Duranty’s 1932 Prize,” November 20, 2003, https://www.pulitzer.org/news/statement-walter-duranty. Pulitzer Prize Board 2002-2003, https://www.pulitzer.org/board/2003.

- Ted Lipien, “Why are US-funded journalists defending Russia, Iran over the Hamas massacre?,” The Hill, October 13, 2023, https://thehill.com/opinion/international/4252199-why-are-us-funded-journalists-defending-russia-iran-after-hamass-attacks/.

- Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website, Box 77, State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944; version date 2013 and the National Archives State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, From Collection: FDR-FDRPSF Departmental Correspondence, Series: Departmental Correspondence, 1933 – 1945 Collection: President’s Secretary’s File (Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration), 1933 – 1945, National Archives Identifier: 16619284, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/16619284.

- Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Polish Writer Listed As His Job Reference Stalin’s KGB Agent of Influence Who Duped President Roosevelt,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), February 12, 2020, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-polish-editor-listed-stalins-kgb-agent-of-influence-as-job-reference/.

- Ted Lipien, “Mira Złotowska – Michałowska — Pro-Soviet Collaborators at OWI and VOA,” Cold War Radio Museum(blog), December 10, 2019, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/mira-zlotowska—michalowska—-pro-soviet-collaborators-at-owi-and-voa/.

- Curator, “The Voice of America World Program Schedules – November-December 1951 – A Year of Changes at VOA,” Cold War Radio Museum, accessed October 15, 2023, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/the-voice-of-america-world-program-schedules-november-december-1951-a-year-of-changes-at-voa/.

- Ted Lipien, “LIPIEN: Remembering a Polish-American Patriot,” The Washington Times, accessed May 13, 2023, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2010/sep/1/remembering-a-polish-american-patriot/.

- Ted Lipien, “VOA Broadcasts in Russian from Munich – A Backstory,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), August 7, 2021, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voa-broadcasts-in-russian-from-munich-a-backstory/. The Information Bulletin of the Office of the US High Commissioner for Germany had a short report in its June 1952 issue on the Voice of America (VOA) Russian-language broadcasts originating from Munich, West Germany.Information Bulletin Frankfurt, Germany: Office of the U.S. High Commissioner for Germany, Office of Public Affairs, Information Division, APO 757-A, U.S. Army, June 1952, http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/History.omg1952June.

- Robert William Pirsein, The Voice of America: An History of the International Broadcasting Activities of the United States Government, 1940-1962, Dissertations in Broadcasting (New York: Arno Press, 1979), p. 219.

- Marek Walicki, Z Polski Ludowej Do Wolnej Europy, p. 111.

- Ibid., pp. 119-120.

- Ibid., p. 117.

- Ibid., p. 116.

- Sarah Ellison and Paul Farhi, “New Voice of America overseer called foreign journalists a security risk. Now the staff is revolting.” The Washington Post, September 2, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/new-voice-of-america-overseer-called-foreign-journalists-a-security-risk-now-the-staff-is-revolting/2020/09/01/da7fa0a8-eba2-11ea-ab4e-581edb849379_story.html. The quote appears in the letter posted online by NPR, https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/7048656/LettertoVOAdirector.pdf.

- John Earl Haynes and Harvey Klehr, Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America, Yale Nota Bene (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2000), pp. 197-199.

- Curator, “Voice of America Censors Soviet Massacre Survivor Józef Czapski And Lies About Its Actions,” Cold War Radio Museum, accessed October 31, 2022, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/timeline/voice-of-america-censors-soviet-massacre-survivor-jozef-czapski-and-lies-about-its-actions/.

- Ted Lipien, “Pro-Stalin Voice of America Propaganda Revealed in 1984 VOA Interview with Józef Czapski,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), September 4, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/stalins-american-voice/.

- Victor Franzusoff, Talking to the Russians (Santa Barbara: Fithian Press, 1998), p. 180. Cited in Ted Lipien, “SOLZHENITSYN Target of KGB Propaganda and Censorship by Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), November 7, 2017, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/solzhenitsyn-target-of-kgb-propaganda-and-censorship-by-voice-of-america/. “

- Mark G. Pomar, Cold War Radio: The Russian Broadcasts of the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (Lincoln: Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, 2022), pp. 165-180. Mark Pomar is a former assistant director of the Russian Service at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and former director of the USSR Division at the Voice of America, where he worked in the 1980s.