Summary

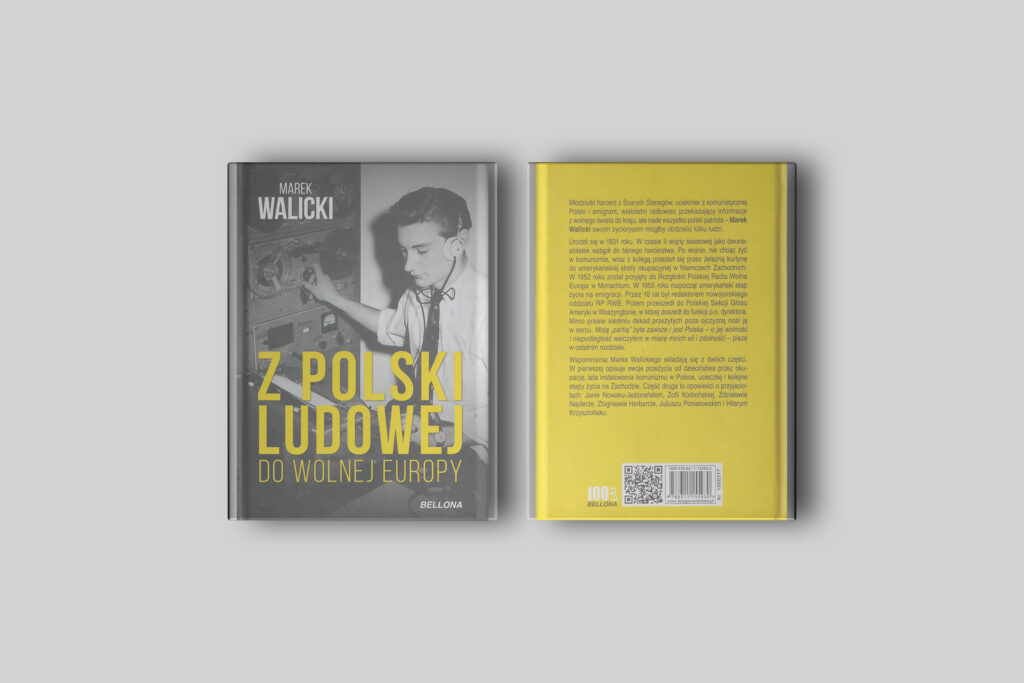

Marek Walicki, a journalist and former broadcaster of the Polish Service of Radio Free Europe (RFE) and the Polish Service of the Voice of America (VOA), is the author of a book, Z Polski Ludowej do Wolnej Europy (From People’s Poland to Free Europe), a memoir of his life and radio career. First published in Polish in 2018 by the Bellona publishing house in Warsaw, his book has been expanded with new chapters and republished in 2023, also in Polish, by Wydawnictwo Ossolineum, part of the prestigious national cultural foundation, library, archives, and research center in Wrocław, Poland.

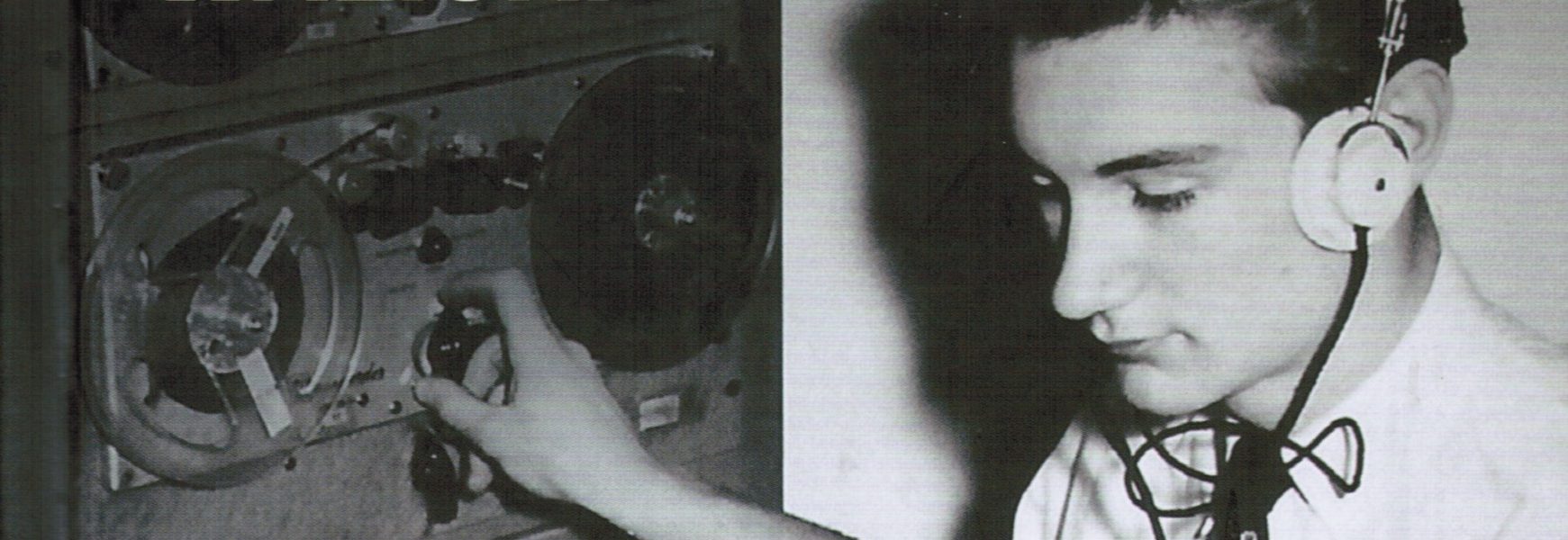

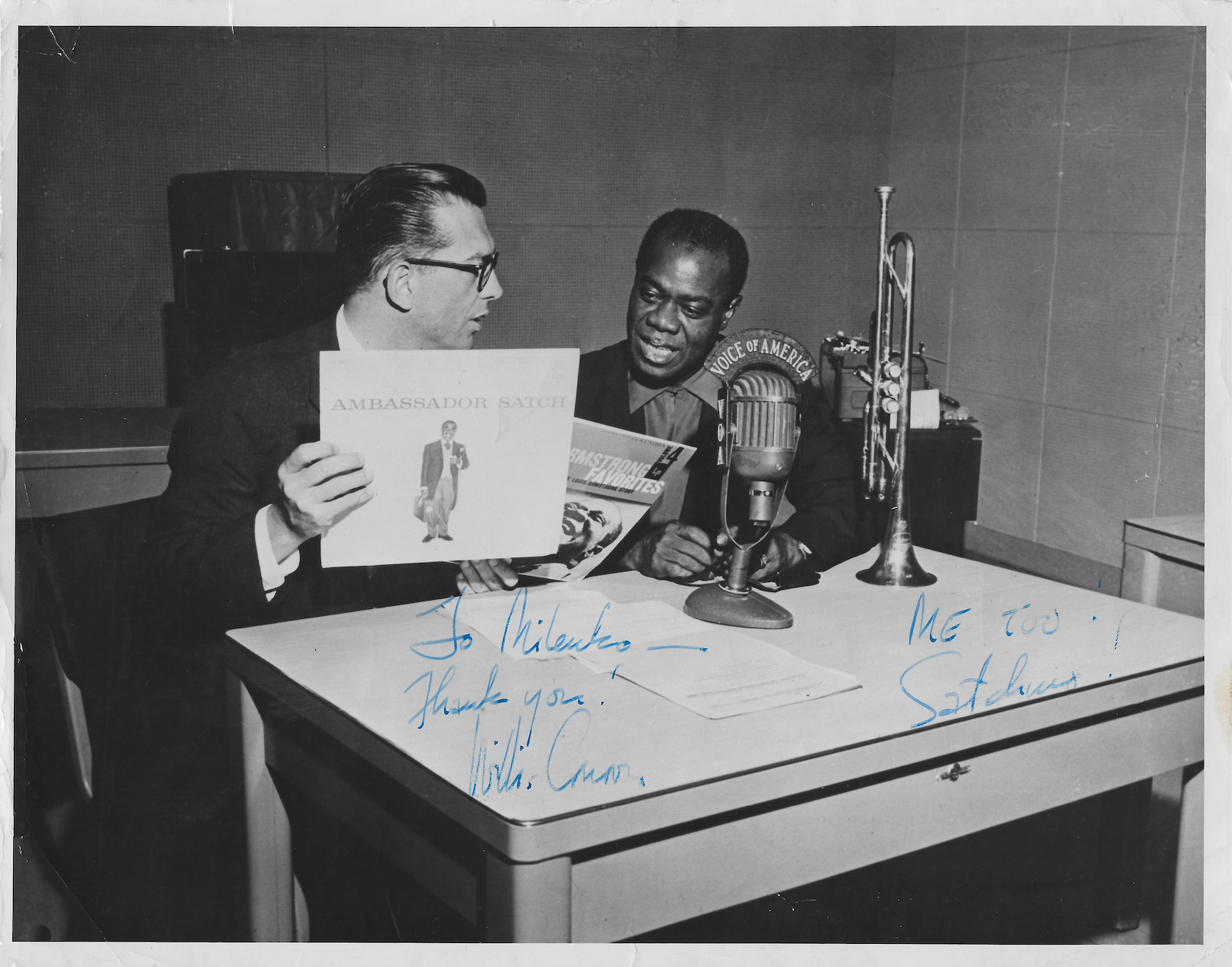

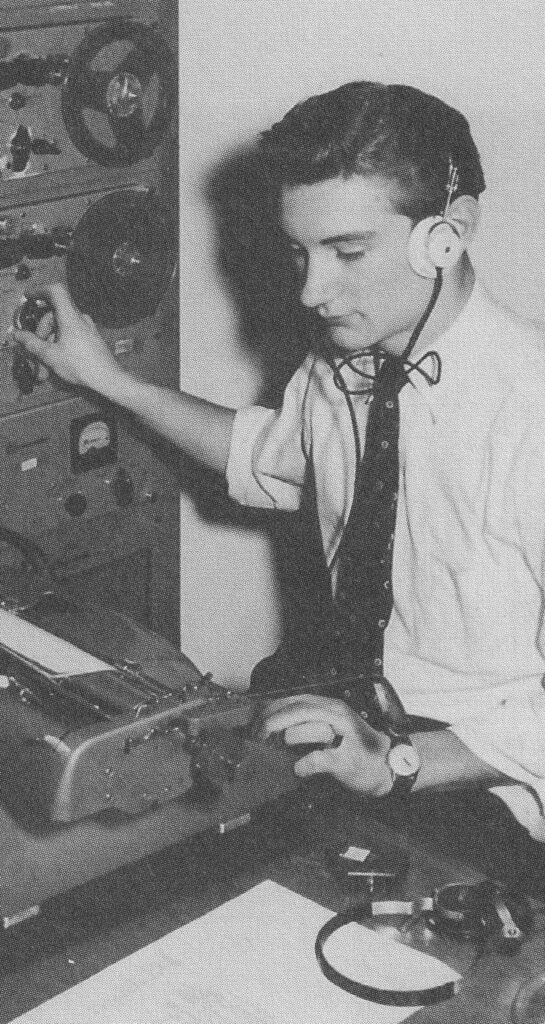

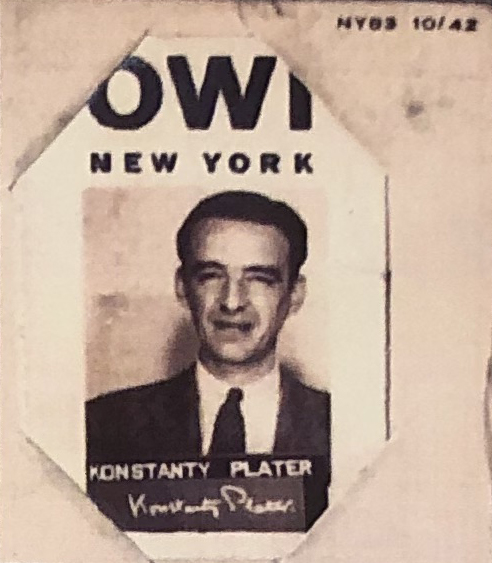

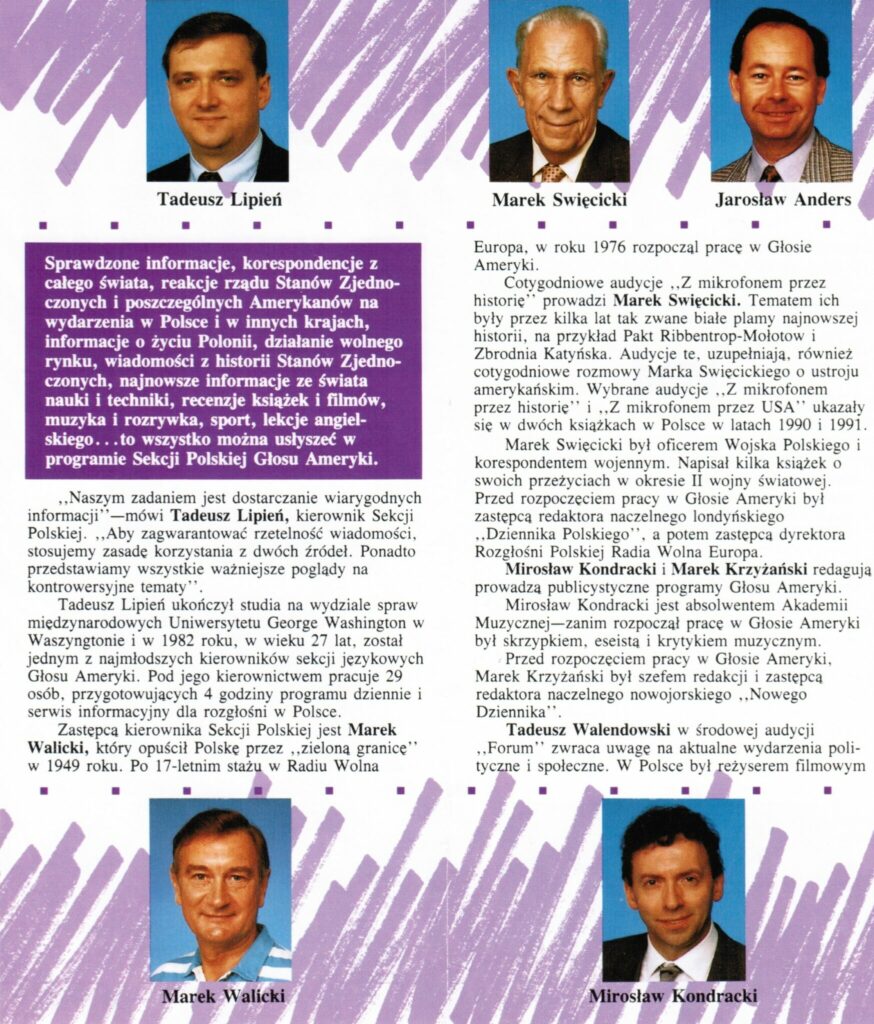

Walicki’s adventure with broadcasting started when he found employment in 1952 at the Voice of Free Poland (later renamed the Polish Service of Radio Free Europe), a radio station in Munich secretly organized and funded by the U.S. government and initially managed by the CIA. There, he worked as a monitor of radio broadcasts from communist-ruled Poland and later as an author of programs and news reports. After emigrating to the United States in 1955 and working in a series of blue-collar and white-collar jobs, he was rehired within a few years by RFE’s Polish Service Bureau in New York. After its liquidation, he worked since 1976 at the Voice of America in Washington, DC, becoming the chief of the VOA Polish Service in 1993 before his retirement in 1994. In 2000, the government of Poland awarded Marek Walicki the Gold Cross of Merit for exemplary public service. In 2010, he received the Commander’s Cross of Polonia Restituta for outstanding achievements. Marek Walicki lives now in the Washington, D.C. area. He is a collector of works by Polish artists and is recognized as a leading expert in the United States on Polish painters of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

I retired with a sense of a well-fulfilled duty, having lived to see a free and independent Poland.

Marek Walicki

This review was written by Ted (Tadeusz) Lipień, Marek Walicki’s former colleague at the Voice of America. Now an independent journalist, he was the VOA Polish Service chief in the 1980s and served as RFE/RL president in 2020-2021. Since Marek Walicki wrote his book for Polish readers, the review includes background information about Poland’s recent history and international radio broadcasting from World War II to the end of the Cold War.

For Poland’s Freedom From Beyond The Green Border – The Story of Radio Free Europe and Voice of America Broadcaster Marek Walicki

By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

Crossing the Green Border for a Life in Exile

The term “green border” had acquired a special meaning in Poland during World War II and the Cold War. It meant crossing borders in search of freedom – leaving without permission from the political authorities when they would not grant it or when seeking it could result in imprisonment. The Poles fleeing from the Russian Empire or Prussia (today’s Germany) in the 19th century for political reasons also used this phrase. For Americans, a green border may conjure an image of a hike through a green forest or meadow, but after World War II, crossing the green borders, an always hazardous enterprise, became even more dangerous. The Soviet Union and its communist satellite states turned them into the Iron Curtain, closely watched by communist guards ready to shoot anyone who managed to breach barbed wires, minefields, and rugged terrain.

After the Soviet-imposed communist regime took control of Poland and established a totalitarian Stalinist dictatorship, Marek Walicki had to sneak through two heavily guarded borders to escape in 1949 to freedom in the American occupation zone in Germany. At the time of his escape, he had just turned 18. The Iron Curtain was already in place. Unlike some other escapees, he was not looking primarily for a better and safer life in the West. He thought he could return with the Americans as a Polish soldier to liberate his country from communism and foreign domination. When this plan proved entirely unrealistic, which Marek realized within a few days after crossing into Germany, he spent most of his adult life abroad in the service of his native country and the United States after the U.S. government employed him as a journalist to oppose Soviet propaganda and Moscow’s military conquests. His life’s new mission was to pierce and destroy information barriers separating Poland and the rest of East-Central Europe from the Free World, hoping that such work would eventually bring freedom and democracy to those he had left behind.

Marek’s book lets readers see his struggle with communist totalitarianism and its propaganda and, to a lesser degree, see what it took for him to overcome the difficulties of being a political refugee and an immigrant in America. He presents his story of a patriotic and idealistic Pole driven by a great sense of duty instilled in him by his family, teachers, and Catholic priests. As a journalist, he showed dedication in carrying out his professional responsibilities and devotion to the highest ethical standards. He saw his work for the Polish Service of Radio Free Europe (RFE) and the Voice of America (VOA) as protecting the truth, not only from the lies of communist totalitarians but also from those in the West who were duped by Soviet propaganda. Now living in retirement in his early 90s, Marek Walicki says with justifiable pride that he helped to secure freedom and independence for his country. His book records his life’s work, from crossing the “green borders” of the Iron Curtain to reporting on the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe.

I decided to escape to the so-called West – to choose the freedom I had longed for since the German occupation.

Marek Walicki

Childhood and War

Born on February 9, 1931, in Poland’s capital city of Warsaw, Marek Walicki grew up in a well-to-do Polish intelligentsia family between the two world wars. As a child, he only experienced life in independent Poland for a few years. Before 1918, Poland was ruled for 123 years by Prussia, Russia, and Austria. More than a century of existence under foreign domination and several failed uprisings against the occupying powers had a profound effect on how the Poles saw themselves and their duties as citizens of once again a free nation and how they responded later to the Nazi and Soviet occupation at the start of World War II and the imposition of communism in Poland with the help of the Red Army and the Soviet NKVD secret police after the war.

Polish children of Marek’s generation who grew up between the two world wars were raised in the tradition of love and sacrifice for their country to ensure that Poland would remain free. Today, these virtues might be dismissed as ugly nationalism by some in the West who never lost freedom or their national independence. But Marek and many other Poles who fought against Nazi Germany and resisted communism were hardly imperialists or oppressors like the German Nazis or Soviet Communists. They were idealists willing to sacrifice everything, even their lives, for freedom and free Poland. The worst they could be accused of was taking excessive risks to defend liberty. Marek and his young friends in pre-World War II Warsaw were brought up on the works of 19th-century Polish literature about the struggles against the occupying powers. In describing his early childhood, Marek writes about family gatherings, at which adults and children read excerpts from Pan Tadeusz, an epic poem by the Polish Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz, describing one of several unsuccessful insurrections against the Russian occupiers.

These patriotic traditions were especially powerful in the homes of the Polish intelligentsia, composed chiefly of upper-middle-class professionals, many derived from the families of the Polish gentry. Łada was the Walicki family’s coat of arms. Both of Marek’s parents were dentists. Before the war, the family lived in a spacious ten-room Warsaw apartment, where his father and mother, Leon and Lidia Walicki, also had offices where they received patients. Marek had a half-brother, Michał Walicki, from his father’s first marriage, a noted Polish art historian, and a younger brother, Ryszard.

While not nearly as rich as some of the aristocratic Polish families, the Walickis could afford to employ a housekeeper-nanny for their two young boys and to send them to spend summer vacations in the countryside, although they usually stayed at the homes of family members or homes of close friends. In his book, Marek writes about his parents’ friendship with the aristocratic Branicki family. These connections proved useful later, helping them survive the German occupation when the Branickis took them into their home during the war after they had lost their apartment in Warsaw due to bombing.

Marek was only eight years old when his and his younger brother’s childhood was interrupted by the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and communist Soviet Russia in September 1939. The unprovoked aggression against Poland by the two totalitarian powers started the Second World War. He and his brother, staying at the time in the countryside in the care of their nanny, were separated from their parents for several weeks, and, for the first time in his life, Marek experienced prolonged hunger. Still a child but already showing courage and initiative, he would leave the house and walk to a neighbor’s home to ask for milk for his hungry and crying brother or go to a nearby town to buy bread. They were later reunited with their mother, who came from Warsaw to fetch them, but his younger brother did not recognize her and started crying.

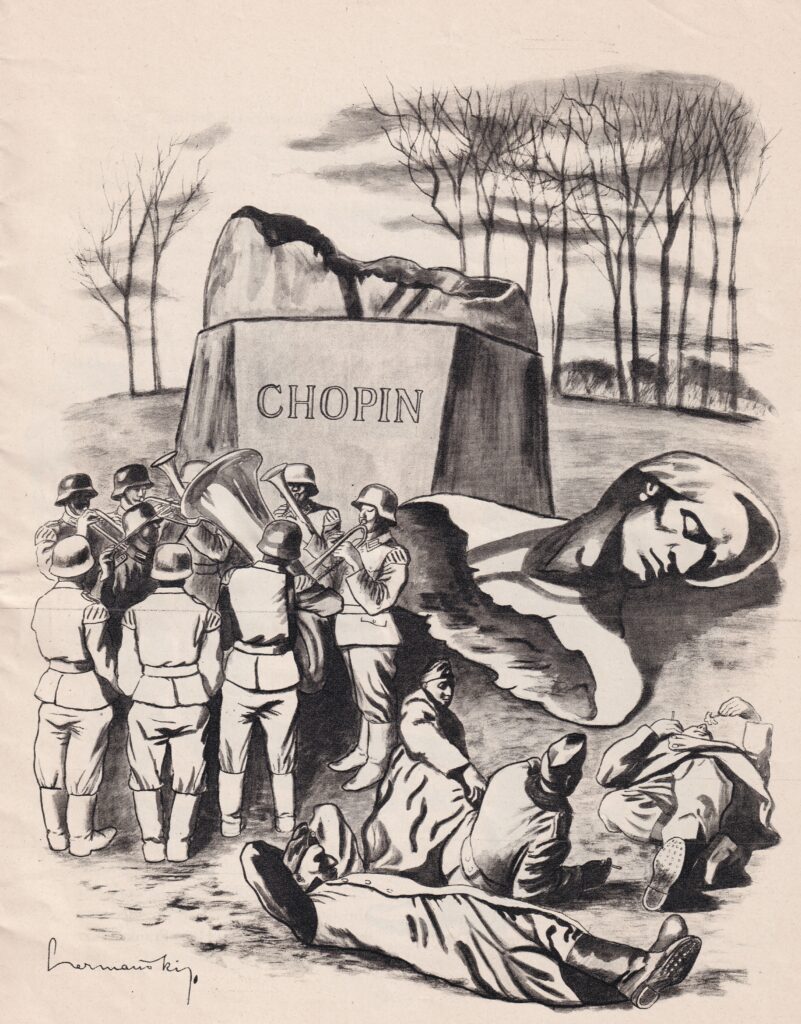

Next came the five years of the German occupation of his homeland. Marek Walicki mentions the Nur für Deutsche (“Only for Germans”) sign at the entrance to the Łazienki Park (Park Łazienkowski), the largest park in Warsaw. The park, where he used to play before the war, was near their home in the city center. It has the famous Frédéric Chopin Monument, the first monument the Germans destroyed in Warsaw during their occupation of the city. The “Only for Germans” warnings to the Poles were not unlike the “For Whites Only” signs that could still be seen for many more years after the war in some parts of the United States. But the Germans inflicted on the Polish Jews and ethnic Poles crimes never seen before in modern history and hard to imagine by those living in the free West: street roundups and executions, deportations for forced labor in Germany, torture and death in Gestapo prisons and concentration camps, and the extermination of Poland’s three million Jews. The death toll of ethnic Poles under the German occupation is estimated at 2,770,000 and 150,000 due to repressions under the Soviet occupation.

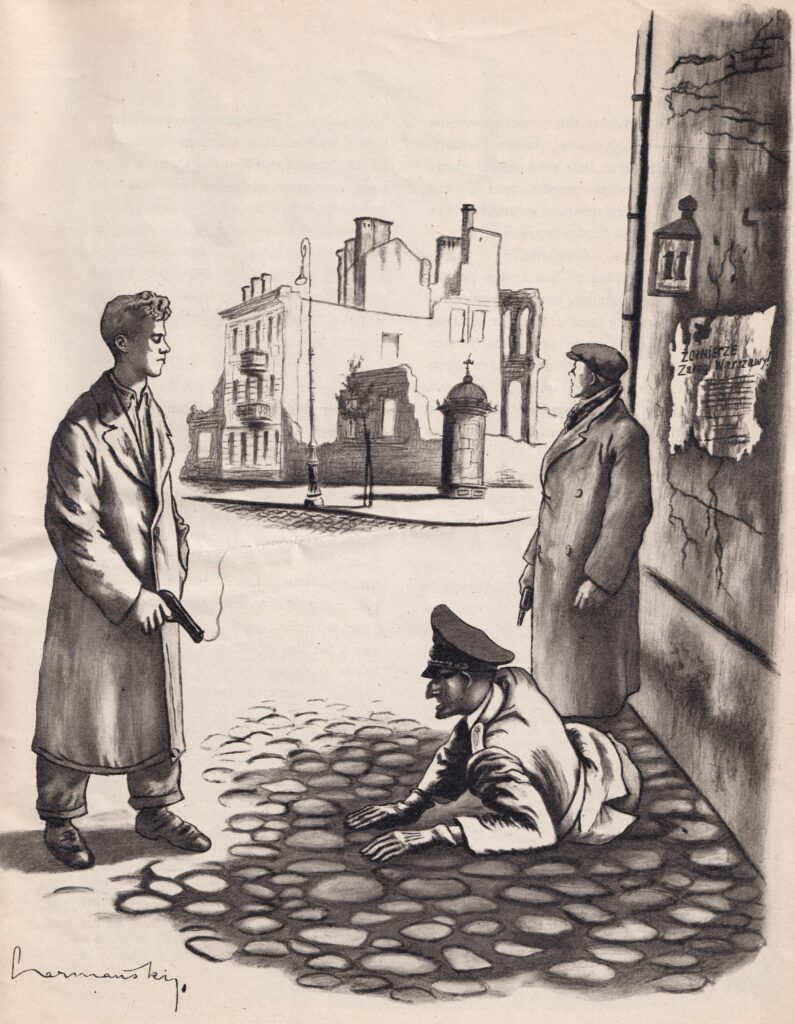

Marek Walicki describes some of the horrors of World War II from the perspective of a young boy. Still not old enough to fight with weapons, he writes about painting patriotic signs on city walls and breaking windows in the city apartments taken over by the Germans. As a young teenager, he observed the deadly 1944 Warsaw Uprising from his refuge home on the periphery of the city, followed by the defeat of the Nazi occupiers by the Soviet Red Army in 1945. He also describes the brutal imposition of communist rule in Poland after the war, with the arrests and killings of “reactionary bandits,” as the Communists called former soldiers of the anti-Nazi Polish underground army. Earlier, the Germans simply called these Polish fighters “bandits,” and an American journalist who was a communist sympathizer described them to American readers as “Home Army terrorists,” using one of the Soviet propaganda terms for anyone who opposed communism.1

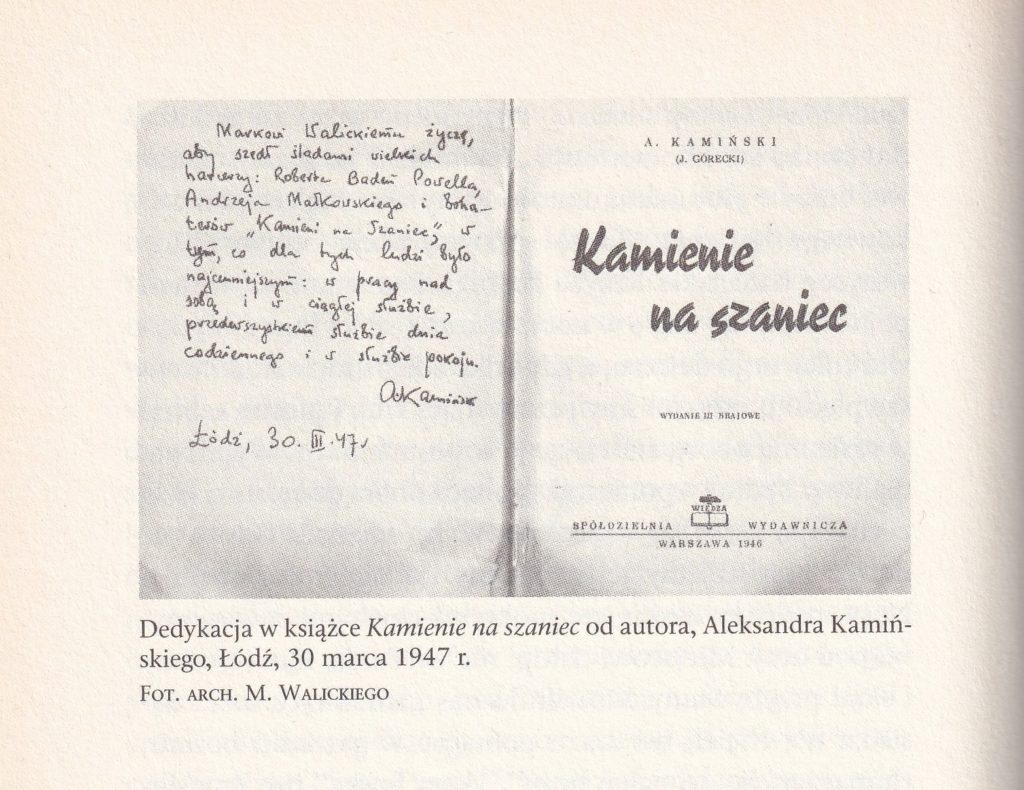

As a twelve-year-old in 1943, Marek Walicki was still too young to be one of the Home Army soldiers, but true to his patriotic upbringing, he joined the Gray Ranks (Szare Szeregi), a codename for the anti-Nazi underground paramilitary unit of the Polish Scouting Association (Związek Harcerstwa Polskiego – ZHP). The Home Army (Polish: Armia Krajowa; abbreviated AK) was one of Europe’s largest anti-Nazi underground resistance movements during World War II. With about 400,000 members in 1944, its loyalty was to the Polish Government-in-Exile in London and the Polish Underground State. In contrast, the People’s Army (Polish: Armia Ludowa; abbreviated AL), which was loyal to Moscow, had only several thousand members in Nazi-occupied Poland. Soviet propaganda statements, repeated by pro-communist Western journalists, falsely claimed that Armia Ludowa was the largest and the most active underground resistance movement in Poland.

None of Marek’s young life’s tragic historical events and challenges broke his spirit. If anything, they made him more determined to fight against foreign and domestic oppressors by whatever means available and wherever he could, even if it meant leaving his home and country and not being able to return for the rest of his life. As he was planning to leave Poland for the free West, Marek still hoped that he would return soon to liberate his homeland.

Hitler-Stalin Pact

As for many Poles of his generation, the right-wing and left-wing totalitarians determined the course of Marek Walicki’s life. He was only eight years old when Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia became allies and started World War II in September 1939 by invading and dividing Poland. The Poles were the first nation to put up armed resistance against German aggression. They were the first to fight Hitler, just as they were the first to resist communism after the war and the first to cause its collapse in the Soviet Bloc. But in 1939, they needed outside help to defend their country, not just against one but two totalitarian powers. One of them was Stalinist Russia. Poland’s Western allies, France and Great Britain did not open a second front in September 1939, as the Polish government had expected based on their promises. The Poles were left to fight alone against a much better-equipped German Army attacking from the west and against a much more powerful Red Army in the east.

The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, also known as the Hitler-Stalin Pact or the Nazi-Soviet Pact, which helped to launch World War II, was signed in Moscow on August 23, 1939, by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov. It included a secret protocol that partitioned Central and Eastern Europe between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin ordered the Soviet invasion of Poland on September 17. Also, under the terms of the Nazi-Soviet Pact, the Soviet Union invaded Finland in November 1939 and annexed part of its territory after the Winter War. The League of Nations declared the annexation of Finnish territory illegal and expelled the Soviet Union. In June 1940, also under the terms of the Hitler-Stalin Pact, Soviet Russia occupied and annexed Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia.

Katyn Massacre

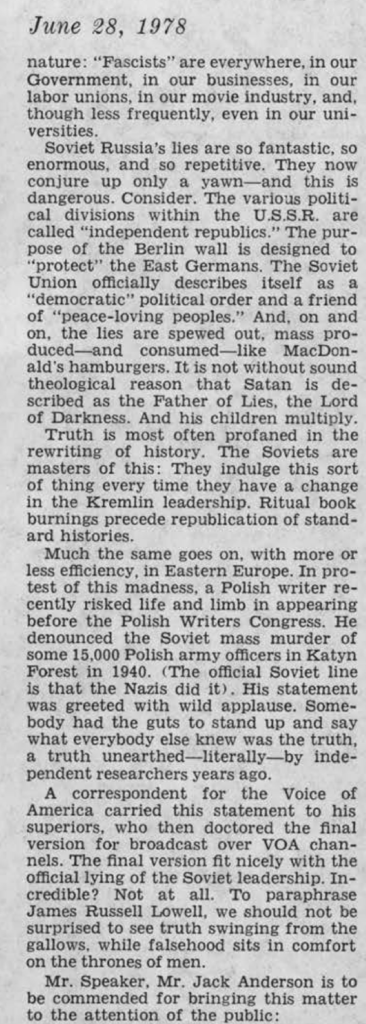

Marek Walicki describes in his book the scandal at the Voice of America over the censoring of a news report dealing with the Katyn massacre sent from Poland in 1978 by a central English newsroom correspondent, Ron Pemstein. He points out that the VOA report was censored by removing pinning the responsibility for the murders on the Soviet Union, as well as removing 1940 as the year when the massacre occurred. Placing the crime in 1940 would show that the Soviet Union was behind it. The Katyn genocide war crime was one of the most significant events of the war. A conclusion and public announcement that Stalin and the Soviet Union were behind it could have ended the American-British-Soviet alliance against Nazi Germany and would benefit Hitler. Had it become known that Stalin ordered the Katyn massacre, President Roosevelt could not have counted on the support of the American people for his naive plan to build post-war peace by making a deal with the Soviet dictator. Had thousands of American or British military officers been found dead, and it became known that the murderer was the leader of an ally, the alliance might not have survived. Roosevelt hoped that the Polish Government in Exile would keep quiet, and Churchill urged the Polish leaders not to accuse the Soviets of committing the crime. Still, what might have been excused for military expediency during the war seemed inexcusable in planning post-war peace and making long-term deals with Stalin. It was even more inexcusable after the war with Germany and Japan had ended. Making deals with a mass murderer would seem profoundly unwise to the people in America and Great Britain. Yet, Roosevelt, with Churchill somewhat reluctantly going along, had decided to trust Stalin in arranging the post-war world order. Once this mistake was made, the U.S. government’s partial censorship of the Katyn crime, mainly by some of the most liberal leaders and members of President Roosevelt’s Democratic Party, although not all of them, continued for decades after the war, including from time to time at the Voice of America but, significantly, not at Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. Some American journalists on the Left also refused to accuse Soviet Russia of committing this crime and presented it as still unresolved.

President Truman, also a Democrat, saw the pro-Soviet tendencies at the bureaucratic Voice of America, placed in the State Department at that time. He approved George Kennan‘s plans for creating a secretly funded U.S. surrogate broadcaster that later became Radio Free Europe to counter Soviet propaganda. However, contrary to Kennan’s suggestion, he put it outside the direct control of the U.S. government bureaucracy and made it a secret CIA operation. The CIA link was later exposed and finally severed in 1972. Since then, Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty have been openly funded by the U.S. Congress. President Truman also stopped the censorship of the Katyn story by the Voice of America, but it returned after a few years.

Marek Walicki points out in his book that the American media reported widely on the Katyn censorship scandal when it erupted again at the Voice of America and referred to what Pulitzer Prize-winning American newspaper columnist Jack Anderson wrote about it in June 1978.

In a strange case of censorship, the Voice of America recently tailored a story about a grisly World War II massacre to fit the Soviet distortion of history. American authorities depleted precisely the facts that the Soviet censorship code prohibits the press from publishing behind the iron curtain. There is a poignant human story behind the incident. A bold Polish writer and poet, Andrzej Braun. dared to protest against the Soviet-imposed censorship before the Polish Writers Congress. It was a dangerous, defiant act. which was reported to the Voice of America.2

Marek Walicki wrote that when the attribution of the crime to the Soviet Union was removed from the Voice of America report, most of the VOA Polish Service staff signed a public protest against “this obvious act of censorship.” He also observed that thanks to this protest, Katyn stopped being a taboo topic at the U.S. government’s radio station. It had been a silent topic since the later period of the Truman administration and the first part of the Eisenhower administration, when, for a few years, the Voice of America did report accurately and extensively on the Katyn story. Before 1950, for a few years, VOA avoided reporting on the Katyn massacre or said very little and did not blame the Soviet Union for the crime. During World War II, the Voice of America, both senior officials and VOA journalists, actively embraced and promoted the Soviet Katyn lie.

Marek Walicki also noted that members of Congress joined in the protest against censorship at the Voice of America in favor of the Kremlin, as they often did during World War II and the Cold War. Without their bipartisan protests, VOA would most likely have remained under Moscow’s propaganda influence for much longer after the war, and the censorship during the period of détente would have been much more pervasive. Some of the strongest criticism of the Voice of America management in 1978 came from Rep. Robert K. Dornan (R-CA), who inserted in the Congressional Record the text of Jack Anderson’s column and his own remarks under the title, “The VOA As Ministry of Truth.” Rep. Dornan made an interesting observation still applicable to right-wing Russian and extreme Western leftist propaganda today, “Western opponents of communism are often denounced by their critics as ‘fascists,’ a Soviet hate word, even though these men and women are sincere votaries of majority rule, popular sovereignty, political equality, a limited state, and the widest range of personal liberty – in other words everything that could possibly exclude them from embracing the statist doctrine of Fascism.”3

When the Red Army invaded eastern Poland in September 1939, thousands of Polish officers who had surrendered or were captured became prisoners of war in Russia. Having decided to destroy Poland’s military and intellectual elites to limit future resistance to the expansion of Soviet borders and influence, Stalin secretly ordered the murder of about 22,000 Polish leaders in genocidal executions in the spring of 1940, which later became collectively known as the Katyn massacre. It was an ominous sign of what Poland and the rest of the world could expect from the Soviet dictator, but to get the American and British leaders and Western public opinion to accept Russian control of East-Central Europe, the Soviet government blamed the Germans for committing this atrocity. President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill went along with the Soviet Katyn lie to keep Stalin as an ally against Germany and Japan for the duration of the war.

However, Roosevelt also naively wanted to obtain cooperation from “Uncle Joe,” as FDR endearingly called him, in securing the post-war peace. U.S. government propagandists in the Office of War Information (OWI), which included the Voice of America, then known under various other names, were hard at work trying to sell to Americans and foreign audiences the myth of Stalin as a wise and benevolent leader and Soviet communism as a progressive political, social, and economic system with only minor correctable imperfections. One of several Communists who turned anti-communist and exposed Soviet influence at the Office of War Information, the parent U.S. government agency of the Voice of America, was Oliver Carlson, an American writer, journalist, founder of the Young Communist League of America in his youth, and lecturer at the University of Chicago. Carlson wrote that domestic OWI propaganda programs, which were essentially the same as VOA broadcasts, presented “the Bolshevik regime” just as “a Russian version of our own War for Independence, Lenin a Russian replica of George Washington, Stalin a compendium of Jefferson, Jackson and Lincoln.”4

Fellow Travelers

I thought my rather lengthy historical background was necessary because an English-language review of Marek Walicki’s book should be particularly interesting, even fascinating, to today’s American and other Western journalists. One of many prominent American newspaper reporters who pretended not to know who had committed the Katyn murders was United Press Moscow correspondent Harrison Salisbury, later a Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times correspondent. He was at the site of the Katyn massacre in 1944 and saw the Soviet lies. Still reporting truthfully on it then or later would have meant he would never have been allowed to return to Soviet Russia for more reporting assignments. He could have also ended up in a Soviet prison. Vladimir Putin still uses the same visa and threat of imprisonment for spying blackmail against foreign correspondents.

Unlike most Americans and most people in Britain and in other Western countries, whom their governments and their journalists deceived about Stalin and Soviet Russia, most well-informed Poles were not fooled by Russian or American propaganda about Katyn during and after World War II. Since the spring of 1943, they knew who was behind the Katyn murders even though the wartime Voice of America, the BBC, and the vast majority of Western journalists eagerly embraced the Soviet hoax. Marek Walicki knew even though he was then a very young man.

In the United States, American communist Howard Fast – also a prolific writer and a later recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize (renamed later the International Lenin Peace Prize) – was in charge of writing and editing Voice of America news when the Germans announced the discovery of the Katyn graves in April 1943. The underground Polish authorities overseeing anti-Nazi military and civilian resistance had their concealed agents among the observers of the German exhumation of the Katyn graves. There was absolutely no doubt from medical and physical evidence that the murders were committed in 1940 when the Soviets were in charge of the Polish military officers and other Polish prisoners of war. To pin the murders on the Germans, Stalin and his propagandists, both Soviet and among Western journalists, insisted that the Polish officers died in 1941 when the area around Katyn was under the control of the German Army.

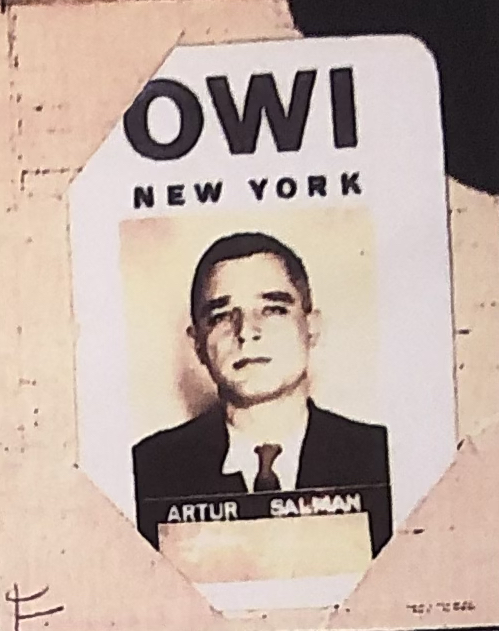

The news of the Soviet responsibility for the massacre quickly spread in Poland through word of mouth. Even some of the Polish Communists, especially those who were survivors of Soviet prison camps, privately said that the Soviets carried out the Katyn murders but remained silent in public. Ironically, a former Voice of America Polish Service editor in New York, Stefan Arski (aka Artur Salman), a Socialist Party activist who had returned to Poland after the war and joined the Communist Party, whom Marek Walicki mentions in his book, became the chief anti-American propagandist and defender of the Soviet Katyn lie. Meanwhile, his former Voice of America colleague, Mira Michałowska (employed by VOA as Mira Złotowska), married a high-ranking Polish communist diplomat and published soft pro-regime propaganda in the United States. She informed American readers of Harper’s magazine in 1946 that Polish Communists were committed to observing the rule of law.5

In January 1944, the NKVD secret police arranged a trip to Katyn for Western reporters. All of them knew or suspected that the Soviet regime was lying in claiming that the Germans had been behind the Katyn murders. Still, they all repeated the Soviet lies without any real effort to challenge them and risk arrest or expulsion from the Soviet Union. The only reporter on the 1944 NKVD-arranged trip to Katyn who chose not to file a report and thus repeat the false Soviet claims about the mass murders was an African-American journalist and writer, Homer Smith, Jr. (1909-1972).6 I wrote in an op-ed that he was a 20th-century fighter for freedom and human dignity, initially fooled by Soviet propaganda but later becoming a critic who deserves to be admired and remembered by more people.7 During World War II, almost all elite Western journalists, including those who were in charge of the Voice of America, repeated Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s lies. However, Homer Smith, who then lived in Russia, chose not to participate in the Kremlin’s propaganda charade. After escaping from the cradle of communism, he later wrote in his book, Black Man in Russia, about his trip to the site of the Katyn massacre.

The Soviet propaganda line that Katyn was a German atrocity had been accepted in April 1943 by President Roosevelt, the Office of War Information in Washington, and its Voice of America radio broadcasting division in New York. Propaganda strategies were secretly coordinated between Washington and Moscow by Robert E. Sherwood. He was a Hollywood playwright, President Roosevelt’s speechwriter, and the head of the Overseas Division in the Office of War Information, which placed him in charge of VOA radio broadcasts. He later coordinated American, Soviet, and British propaganda from the OWI office in London. While still in New York, he advised VOA broadcasters in his “Weekly Propaganda Directive,” dated May 1, 1943, that “some Poles” who did not accept the Soviet explanation may be cooperating with Hitler in causing division among the allies. Poland was an anti-Nazi ally of the United States and a Nazi-occupied country where such cooperation with Germany on the part of the underground state, its underground army, and the Polish armed forces fighting the Germans in Italy was beyond unthinkable. After Moscow broke diplomatic relations with the Polish Government-in-Exile over its request for an independent investigation of the Katyn massacre by the International Red Cross, Sherwood was pushing the Soviet propaganda line that the Poles who did not accept the Kremlin’s position on Katyn were supporters of Hitler and Fascism. “Some Poles are consciously or unconsciously cooperating with Hitler in his campaign to spiritually divide the United Nations, Sherwood wrote. 8 To him, Poland may have appeared as a small country in Eastern Europe, and the Poles were an obstacle to President Roosevelt’s plans to win the war and postwar peace with Stalin’s cooperation. Had 15 thousand or more American or British military officers been killed by a still unknown country, it is doubtful that Sherwood would call an American or British appeal to the International Red Cross for conducting an impartial investigation as a sign of support for Hitler.

Western journalists who were pro-Soviet or did not want to be thrown out of Russia, took a similar position and embraced the Soviet propaganda lie on Katyn. One of them who went on the NKVD-arranged expedition to Katyn in 1944 was Kathleen Harriman, an American journalist working during World War II in Great Britain and Russia as an occasional freelance news reporter for the U.S. government’s Office of War Information, which included the Voice of America. In London, she worked for Wallace Carroll, one of OWI’s and Voice of America’s strongest supporters of Soviet Russia and Stalin’s propaganda. She was also the daughter of the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union – young, attractive, rich, and made famous in the Soviet press. Toward the end of her stay in Russia, communist dictator Joseph Stalin gave her a gift – a horse who had served at the battle of Stalingrad – in an unusual gesture of gratitude to an American. He also gave a horse to her father, W. Averell Harriman, the fourth richest man in America in 1946, according to a British illustrated magazine article about Kathleen Harriman, as she prepared to be the embassy hostess at her father’s next ambassadorial post in London.9 In January 1944, as a journalist and her father’s representative when he was U.S. ambassador in Moscow, she helped to save Stalin’s reputation in a secret report she wrote for the State Department in Washington by misinterpreting the evidence of one of his most cruel atrocities. In a victory for Soviet propaganda, she exonerated him of the brutal murders of thousands of Polish military officers. Stalin was grateful to the Harrimans for literally helping him get away with murder.

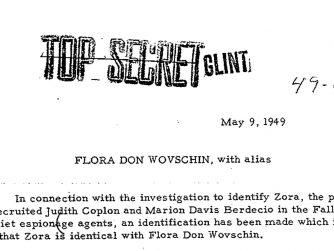

According to U.S. Ambassador to Poland Arthur Bliss Lane, who served in Warsaw from 1945 until 1947, Kathleen Harriman’s report was the only one in the Katyn file at the State Department when he requested it before starting his ambassadorial assignment. All other reports that could have pointed to the Soviet responsibility for the Katyn massacre were presumably removed by unknown State Department employees. It could have been the work of the convicted perjurer and suspected Soviet spy, American diplomat Alger Hiss, or a Soviet spy, a daughter of affluent Russian immigrants and Barnard College graduate, Flora Don Wovschin (codename “Zora”). During World War II, she was employed at the Office of War Information and the Voice of America library and research unit in New York. She later worked at the State Department before defecting to the Soviet Union.10 When, after the war, the FBI started efforts to identify her and find her, Wovschin fled in 1946 or 1947 to the Soviet Union, where she renounced her American citizenship and married a Russian engineer. The FBI received information that Wovschin later had gone to North Korea to work as a nurse and had died there.11

Three years after she wrote the report about the Katyn massacre with her false conclusion that it was a German rather than a Russian war crime, Kathleen Harriman (Kathleen Mortimer after her marriage) was back in the United States, working as a volunteer for the U.S. government to help launch VOA Russian-language radio broadcasts. She was not responsible for the content of these programs, which went on air for the first time in February 1947. VOA did not broadcast in Russian earlier, even during World War II, apparently in order to avoid offending Stalin. A State Department diplomat, Charles W. Thayer, was in charge of launching the Russian Service and later became VOA director. It was Thayer who recruited Kathleen Harriman as a volunteer employee in violation of government regulations.

As a popular figure with Stalin and the Russians, Kathleen Harriman was a perfect choice to help the head of the newly established Voice of America Russian Service start broadcasts to Russia in 1947. Their purpose was not to point out Soviet human rights abuses or to criticize communist leaders. It was to show that the United States was a friendly country wanting better relations with the Soviet Union. As one of the early VOA Russian broadcasters, Helen Yakobson, recalled, in the first broadcasts to Russia, “No direct criticism or attacks on the Soviet system were permitted.” She further noted, “After all, they had only recently been our allies.”12 The Russian-American intellectual and music composer Nicolas Nabokov, a cousin of writer Vladimir Nabokov of Lolita‘s fame, who helped to launch VOA Russian-language broadcasts, described his brief employment with the Voice of America “as something hilariously funny, earnest in its aims, and as disappointing as sweet-sour pork in a third-class Chinese restaurant.”13 The content of VOA Russian broadcasts only became critical of the Soviet Union and Stalin’s human rights violations after President Truman intervened and announced his “Campaign of Truth” in a foreign policy speech on April 20, 1950, to members of the American Society of Newspaper Editors as the answer to harsh Soviet propaganda attacks on the United States and its allies.

The Soviet manipulation of Western public opinion was a major and longlasting endeavor helped by many fellow travelers among the Kremlin’s witting or unwitting agents of influence. The role model for the Western journalists who had embraced Soviet propaganda was the New York Times Pulitzer Prize-winning Moscow correspondent Walter Duranty, who deliberately lied about the Soviet-engineered famine that took the lives of millions of Ukrainians in the 1930s. As revealed by American journalist and writer Eugene Lyons, who had worked as a reporter in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, was initially a pro-communist fellow traveler and interviewed Joseph Stalin, but later became a strong critic of Communism and Soviet Russia, Duranty and other Western journalists based in Russia later attacked Welsh reporter Gareth Jones, who told the truth about this unimaginable crime against humanity.14 Yet, still too ashamed to face up to this historic failure of Western journalism, the Pulitzer Prize Board refused in 2003 to take away Duranty’s 1932 Pulitzer Prize. Walicki’s book is, therefore, a valuable resource since the influence of Soviet propaganda has never been eliminated in the United States. It is now experiencing reemergence under Russian President Vladimir Putin, helped this time not by the radically left-leaning but by some of the radically right-leaning American politicians and journalists.

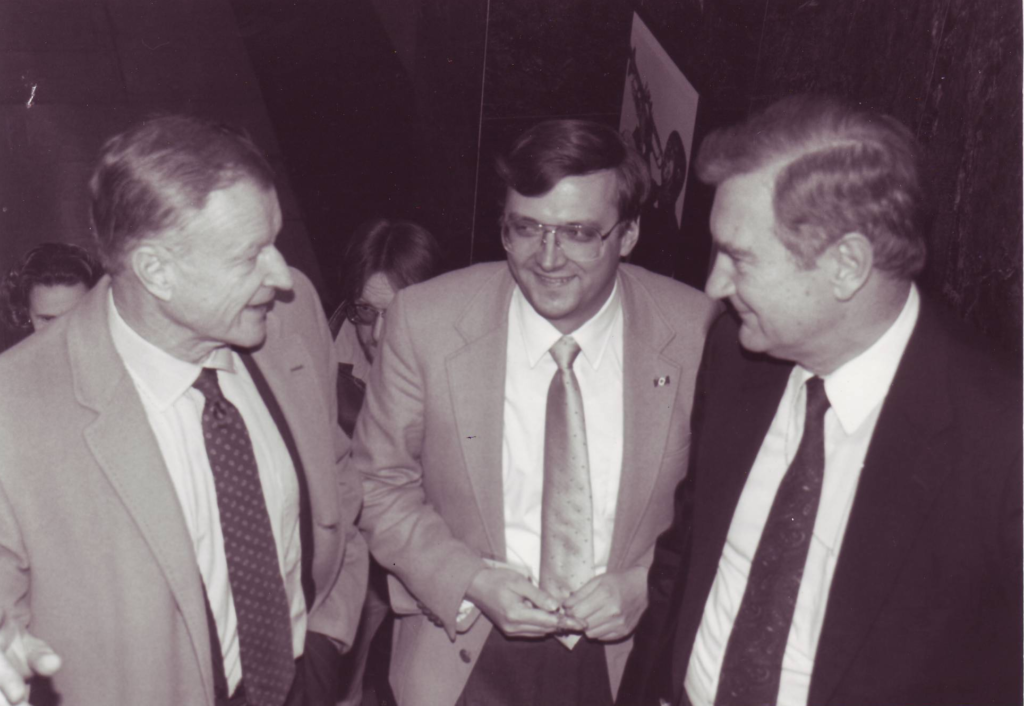

Some young Americans or even the older ones who watched a recent interview the right-wing American commentator Tucker Carlson conducted with Vladimir Putin and heard the Russian autocratic ruler’s revisionist history may not know that Red Russia also attacked Poland and occupied part of its territory at the start of the Second World War. When I was the Voice of America Polish Service chief in the 1980s, and Marek served as my deputy, Tucker Carlson‘s father, Richard Carlson, was the VOA director (1986 to 1991) and was very supportive of our broadcasts to Poland. He once brought Tucker, then a teenager, to tour VOA services and learn what we were doing. If his son had learned anything from his visit with anti-Soviet VOA broadcasters, it did not help him to challenge the Russian autocrat when, in a lengthy interview, Putin repeated Stalin’s old lies and tried to blame Poland for starting World War II.

The Gulag

The truth omitted and distorted in the Carlson-Putin interview was that both Hitler and Stalin had started the war and that soon after annexing eastern Poland, Stalin ordered hundreds of thousands of Polish citizens – men, women, and children – deported in 1940-1941. Whole families, taken from their homes during the night, were packed into cattle trains and sent to Soviet slave labor camps and collective farms. Many, especially the youngest and the eldest, died already during the transport from cold, hunger, and lack of medical care; their dead bodies were sometimes thrown from the trains into the snow, and many more perished in unbearable conditions in Siberia and in other remote parts of the USSR. In one of his “Kolyma Tales,” Russian writer Varlam Shalamov (a Gulag survivor like his friend Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn) described the slave labor camps there as “Auschwitz without the ovens.”15 According to estimates by the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (IPN), roughly 320,000 Polish citizens were deported to the Soviet Union, of which nearly half, 150,000, died under the Soviet rule during World War II as a result of starvation, disease, hard labor, harsh weather, degrading treatment, torture, and executions.

But just as Putin lied to Tucker Carlson and his audience in 2024 and VOA’s most famous Communist Howard Fast misled radio listeners during World War II about the Katyn massacre and other Soviet atrocities, VOA official Dr. Owen Lattimore earnestly told National Geographic magazine readers that workers at the infamous Kolyma gold mines were all volunteers fed hot house tomatoes and other vegetables to improve their diet16, and fellow traveler American journalist Anna Louise Strong, who corresponded with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, tried to convince Americans in her 1946 propaganda book, I Saw The New Poland, that the Poles were not forcibly deported but moved to Siberia; the Soviet authorities provided “kitchens giving [them] food at every station.”17 And even though Putin is much more successful now in duping right-wing Americans and conservative media commentators like Tucker Carlson, the old Soviet and Marxist narratives, still promoted by Russia and its proxies, continue to influence many left-wing journalists, including some who now work for the Voice of America.

Recent media reports revealed that VOA editors and reporters refused to call Hamas “terrorists,” and a few reporters posted antisemitic memes and other such material on social media.18 Young VOA journalists might benefit from reading in Marek Walicki’s book how, in 1941, he risked his life as a ten-year-old fleeing alone without permission from a summer vacation camp to return home in Warsaw as the Germans were hunting for Jews of all ages, including children, in the forest near the ghetto. Marek also writes how, in 1943, his mother brought home a thirteen-year-old boy and introduced him as Zbyszek Mokracki, saying he was an orphan. Marek hoped that Zbyszek would play with him, but he discovered that the boy seemed always sad, did not want to play, and refused to go outside. The Walickis’ apartment was located near the feared Gestapo headquarters. In writing about their new houseguest, Marek also described how thousands of burning pieces of paper were falling from the sky at that time, some of them written in Hebrew. The Germans were burning Jewish homes as they tried to suppress the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising while sending its remaining inhabitants to the gas chambers. After some time, the boy disappeared from their apartment. Marek’s mother told her son later that Zbyszek was Jewish and was sent off to a Polish Catholic convent to keep him out of the Gestapo’s hands.

Marek Walicki’s reminiscences seem particularly relevant today, as hunting for Jews, including children, resumed in the 21st century. Hamas terrorists sought Jews out in Israel to murder or take them as hostages. Sadly, many current VOA news reporters do not see the connection between Hamas and German Nazis and between Soviet Marxist and Putin’s propaganda and their own biases as journalists. In reporting on the admittedly great suffering of Palestinian civilians, they fail to note that Hamas had started the war and could end it by releasing all hostages, stopping the launching of rockets targeting Israeli civilians, and ceasing their terrorist attacks. These journalists rarely refer to rapes and taking hostages by Hamas as war crimes. Unfortunately, Marek Walicki’s book is not yet available in English translation because much could be learned from it by American-born reporters or foreign-born who know little about life under Fascism and Communism.

Life Under German Occupation

Later in 1943, when the Walickis’ Warsaw apartment was destroyed during one of the Soviet bombing air raids, the family found shelter in the Wilanów district of Warsaw in the left wing of a former royal palace belonging to the Branicki family. Before the war, the Polish owners of the Wilanów Palace, Count Adam Branicki and his wife Beata, were patients and friends of his parents. At the beginning of the war, the Germans arrested the Polish aristocrat and his sister and confiscated his art collection and landholdings. However, after the intervention of the Italian royal family, the Gestapo released him and allowed the Branickis and their guests to live in the Wilanów palace. There, Marek met young Poles, only slightly older than he was, who were members of the Home Army. One of them, Janusz Radomyski, who was in love the Branickis’ daughter Anna, took Marek’s oath to join the Polish resistance movement and put him in touch with several scouts known as Zawiszacy, the anti-Nazi scouting group of boys and girls aged 12 to 14. They were the youngest conspirators who served as couriers carrying messages and participating in civil resistance by painting anti-Nazi slogans on buildings and distributing underground newspapers. Marek writes that some packages he had to deliver were too heavy to have only papers but added that, in obeying orders, he did not try to see what was in them.

Someone like Marek who as a child risked his life in the struggle against Fascism could not be easily intimidated or deceived by Communists and other totalitarians. He would also not be easily discouraged later by new disasters and challenges when working as a Cold War journalist.

VOA and the Warsaw Uprising

Marek Walicki was only 13 when the Warsaw Uprising began on August 1, 1944. He wanted to join the fighting in the city, but presumably, his parents would not permit it. Marek writes that on August 3, the Germans executed in the Wilanów Palace park several Polish insurgents whom they had captured. It soon became clear that the uprising was not going well for the Polish Home Army. Marek observed one unsuccessful action by a unit of Polish insurgents at the palace where his family was staying. Janusz Radomyski, the fiancé of the palace owner’s daughter, Anna Branicka, wanted to free her and her mother from house arrest by the Germans. Before the uprising, he had recruited Marek to join the anti-Nazi resistance as a young scout. Marek’s father thought it was a careless and unnecessary action that put the civilians in danger of German retaliation.

The uprising lasted 63 days. It failed due to Stalin’s refusal to send the Red Army or the Polish troops under his command to help the fighting insurgents in Warsaw or even to give permission for American and British planes to land on the Soviet-controlled territory after dropping weapons and supplies for the Polish Home Army. The Polish casualties were horrific – about 16,000 dead insurgents, many more wounded, and the civilian deaths estimated between 150,000 and 200,000, the majority from mass executions by German troops and foreign units under German command. After the failure of the uprising, the Germans forced the remaining civilians to evacuate from the city. They blew up buildings, destroying in revenge almost the entire city while the Soviet Army stood idle on the other side of the Vistula River.

The Walickis had to abandon the relative safety of the Wilanów Palace grounds and found refuge in a nearby home as the German-ordered evacuation of Polish civilians continued. In an area under their control, where the Walicki family was staying, the Germans forbade all men and boys over 10 to leave their homes. Still, Marek had decided to go to a nearby house, whose occupants were listening to the forbidden foreign radio stations, mainly the BBC. The British Broadcasting Corporation radio programs are mentioned in numerous memoirs by Polish Home Army leaders and fighters. Almost no one mentions the Voice of America, which largely ignored the Jewish Holocaust and the Warsaw Uprising.

A German soldier stopped Marek as he was walking outside to get to the house, whose inhabitants had an illegal radio receiver, and could have killed him. Instead, the soldier motioned with his pistol and ordered Marek in broken Polish, “take me to a store for beer” Marek did, of course, what he was told. He and the German soldier walked together to the store and found it closed. The soldier banged on the door and demanded from the frightened owner – a woman who emerged from the basement – to tell him if she was hiding any Banditen. After hearing her denial, he demanded beer and a toothbrush, which, fortunately, she was able to provide. Pleased with himself, the German told Marek to go home: Raus nach Hause, and even escorted him back home when Marek, fearing being killed by other German soldiers, politely asked him to do so.

Unknown at that time to young Marek, the Soviet propaganda presented Home Army insurgents in Warsaw as pro-fascist adventurers. The pro-Soviet Voice of America leadership and journalists sided with Stalin on the Warsaw Uprising by ignoring it, even though President Roosevelt wanted to provide help to the Polish Home Army soldiers fighting the Germans in Poland’s capital. Had Marek Walicki or Jan Nowak joined VOA in 1944, they would have found, in the words of an Austrian-Jewish refugee journalist, Julius Epstein, “extreme left-wingers who indulged in a purely and exaggerated pro-Stalinist propaganda.”19 Epstein was, until 1945, an editor on the German desk of the Overseas Branch of the Office of War Information in New York. The OWI included the Voice of America, although its wartime broadcasts were disseminated under various names. In reporting on one of VOA’s wartime scandals, the New York Times Washington correspondent and bureau chief Arthur Krock observed that its radio programming “conforms much more closely to the Moscow than to the Washington-London line” and follows “the personal and ideological preferences of Communists and their fellow-travelers in this country.”20 A Polish journalist based during the war in London, Czesław Straszewicz, who later worked for Radio Free Europe, wrote after the war,

… with genuine horror, we listened to what the Polish language programs of the Voice of America (or whatever name they had then), in which in line with what [the Soviet news agency] TASS was communicating, the Warsaw Uprising was being completely ignored.21

The wartime Voice of America also practically ignored the Holocaust of European Jews, probably because Stalin did not care much for protecting Jews and sent many of them to the Gulag.22The Soviet dictator wanted American war propaganda to focus on the Red Army fighting the Nazis, the opening of the second front in Western Europe, and facilitating his takeover East-Central Europe. American and foreign-born propagandists in the Office of War Information and the Voice of America did not disappoint him. The Office of War Information also produced propaganda films in support of the illegal internment of Japanese Americans, modeled in concept, although not in deaths and cruelty, after Stalin’s deportations of ethnic groups to the Gulag.

Still, President Roosevelt wanted the Warsaw Uprising to succeed and, perhaps also to secure for himself the Polish-American votes in the 1944 U.S. presidential elections, made appeals to Stalin for help, which the Soviet dictator rejected. Stalin showed his contempt for the Warsaw fighters in a secret message to President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Churchill on August 22, 1944: “Sooner or later the truth about the handful of power-seeking criminals who launched the Warsaw adventure will be out.”23

Roosevelt’s Gift to Stalin

As World War II was nearing its end, Marek Walicki had no way of knowing that his future and that of his country was being decided not by his compatriots but secretly and without the knowledge of the multiparty Polish Government in Exile, by the leaders of the great powers in Moscow, London, and Washington. Regardless of what the Western leaders may have wanted for Eastern Europe after the war, the Soviet dictator was not going to give up on his plan to keep the territories the Red Army had occupied in 1939 and his desire to place Poland and other neighboring counties under Russia’s control. Critical to misleading the West about Stalin’s intentions was the perceived need to hide his enormous crimes from Western public opinion.

One of the most horrific of Stalin’s crimes was the Katyn massacre. Helping the Soviet regime with propaganda to cover up the Katyn mass murders, the Gulag slave labor camps, and other communist atrocities were many left-leaning Western journalists, a few politicians, and a large number of intellectuals. Fortunately, there were also American journalists, diplomats, and politicians, including members of the U.S. Congress of both parties, who were pointing out, in public, but more often privately, especially while the war with Germany and Japan was not yet won, that President Roosevelt’s trust in Stalin was a colossal mistake. However, their warnings would not be acted upon until President Truman had concluded that the Soviet dictator was a mass murderer with who could not be trusted.

After the end of World War II, Marek Walicki, along with millions of other East-Central Europeans, was doomed to pay the price for the world conflict started by Hitler and Stalin. After Hitler betrayed his alliance with the Kremlin and attacked Russia in June 1941, the Soviet Union emerged as America’s most valuable military ally. Roosevelt and Churchill secretly promised Stalin at the wartime Big Three conferences in Tehran and Yalta that he could keep the eastern part of Poland he had already acquired in his earlier deal with Hitler. Not only the Poles but also the Ukrainians and the Belorussians, who represented the majority of the population of pre-war eastern Poland and wanted to have their own nation-states after enduring years of Soviet communist terror, were not consulted.

Marek Walicki’s book is a memoir, not a detailed historical account. Written for a Polish reader, it omits the historical background of events he describes in his young life. Still, as a good journalist, he sometimes presents the drama of the times in one or two sentences. Marek was still a young teenager when he saw the first Soviet soldiers and shared his excitement with Hanna Garlińska, the former wife of his half-brother Michał Walicki. She replied to him with a severe expression, “Don’t rejoice, dear Marek; difficult times are coming.” Red Army soldiers stole from the Poles whatever they could. Marek writes about returning to their room in the Wilanów Palace administrative building they left a few months earlier. (They had moved earlier from the part of the left wing to the administrative building next to the right wing of the palace. The administrative building had heating, which the palace did not have.) The green leather on his father’s dentist chair, which he brought from Saint Petersburg to independent Poland in 1918, was carved entirely out. The chair was full of human feces, and the whole room was littered with destroyed books, including pages ripped out of a pre-revolutionary Russian encyclopedia. Marek and his mother also discovered that the Soviet soldiers left small pieces of dental gold foil on the floor, not realizing their high value.

Marek Walicki proved he had courage, independence, initiative, and youthful foolishness when, at the end of the war, he became the primary breadwinner in his family at the young age of 14. His parents were not yet working, and there was no money to buy fuel and food. Too young to be a worker, even if he could find employment and his parents would permit it, he decided to collect wood, which, as he noted, became as valuable as gold. His father had permission from Count Branicki to cut wood in his forest, but Marek found a better way by transporting already cut logs previously used by the Germans to cover the ammunition dumps near their home. For his plan, he secured the help of a Polish peasant with a horse wagon and a willingness to take risks.

To get the wood out of the forest, they had to drive through an area full of abandoned explosives and get the logs to load on the wagon by removing them from the ammunition dump. Marek and his helper survived; the peasant kept half of the wood for himself, and the Walickis had enough to stay warm the entire winter.

Marek also learned how to build fireworks from gunpowder extracted from German signal rockets that burned in various colors. For some reason, these homemade fireworks were highly sought after by the peasant boys, who could pay for them with food probably stolen from their parents. Marek briefly lost his sight when a small amount of gunpowder he tried to light with a match exploded in his face, burning his eyebrows. Some young boys in the neighborhood died from playing with an artillery shell. Marek’s father, who discovered gunpowder stored under his son’s bed, explained to him that the whole house would be destroyed and many people would die if it exploded. Marek had to hide his stash of gunpowder in the garden. He wrote that after his parents returned to work in dentistry, his job ended, and to his great disappointment, they once again treated him as a child.

Communist Repressions

Life in Poland, freed from the Germans by the Red Army in 1944-1945, did not mean the end of terror for Marek Walicki’s family. He wrote that on the first day of the “liberation” of the area near Warsaw, Soviet soldiers raped dozens of local women, several of whom died, their bodies left in the snow. In January 1949, the Polish communist secret police arrested his older half-brother, Michał Walicki, a noted art historian, and falsely accused him of collaborating with the Germans. At about the same time Marek Walicki started his full-time work at Radio Free Europe in Munich after his escape to the West, a court in Warsaw sentenced Michał Walicki to a five-year prison term for being a member of the anti-Nazi Polish Home Army counter-intelligence unit, which collected information about the communist press, the Polish Communist Party, and its underground military formations. Marek pointed out that Colonel Józef Różański, an NKVD agent who, after the war, joined the Polish Ministry of Public Security (UB) and personally tortured former anti-Nazi Home Army soldiers, as well as Communists who fell out of favor, complained in a secret memorandum that the prison sentence was too short and should more severe. Michał Walicki, who consistently denied the charges of helping the Germans in any way, was released from prison in 1954.

Soviet and Polish communists often falsely used the fascist label against those non-communist Poles who had risked their lives fighting the Nazis during the German occupation or served as officers and soldiers in the Polish Army fighting Nazi forces in the West simply because these Poles were opposed to communism and Poland becoming a Russian colony. Many innocent men and women were tortured and executed. Others spent years in prisons in Poland or were sent to the Gulag forced labor camps in Russia.

Marek writes about Anna Branicka-Wolska whom the Soviet NKVD arrested with her father and her mother, Beata Branicka, and sent to Siberia. Anna’s fiancé, Janusz Radomyski, who had recruited Marek to be a member of the anti-Nazi resistance, was taken by the Germans as a prisoner of war after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising and ended up in the West after the war. Beata Branicka wrote moving love letters to him from Russia, which he did not receive. She survived her ordeal in Russia and returned to Poland with her family in 1947, but her fiancé, thinking she was dead, married another woman. Her love letters were published in Poland in 1990 in a book, Listy niewysłane (“The Unsent Letters”).

The Polish communist secret police detained and interrogated Count Branicki for a few more weeks in 1947 after his return from Russia. Anna, who was a member of the Home Army and participated in the Warsaw Uprising, was also interrogated. The regime confiscated the family’s remaining property, including the Wilanów Palace, where the Walickis found refuge during the war and where Anna helped to organize a field hospital for the Warsaw Uprising soldiers, which the Germans discovered and put her under house arrest with her mother and sister. The Communists also appropriated the remaining artworks Count Branicki managed to save from the Germans and the Soviet soldiers.

The Voice of America, still dominated by Soviet sympathizers, did not broadcast Information about communist repressions in Poland or Polish soldiers in the West who refused to return to their homeland. At the time of his escape to the West, Marek did not know that the Western Allies had already demobilized the Anders Army, which he had hoped to join. There were diplomatic protests by the American and British governments after the war. Still, there were no plans to force Russia to honor the promise of free and democratic elections in Poland and the rest of East-Central Europe. In 1949, the Soviet Union successfully tested its first atomic bomb thanks to the help of American Communists and British agents supplying the Soviets with stolen Western military secrets. The Soviet nuclear blackmail was in full swing.

Marek writes in his book that when cold and hungry, he crossed the Czechoslovak-German border in late October 1949 in rain and snow, he had no idea he would later work as a journalist and help to liberate his native land, not with weapons but with words. His big break came when, quite by accident, he became an employee of the Voice of Free Poland (later the Polish Service of Radio Free Europe) in 1952, initially as a monitor of radio broadcasts from Poland and later as an author of programs and news reports.

The Escape

I increasingly felt that we were living in a cage, that there was no future for me there.

Marek Walicki

Marek made his decision to escape through Czechoslovakia to the American occupation zone of Germany in 1949 when he saw the Communists, in his words, “torture, murder, and imprison thousands of Polish patriots.” He and his friend, Marian Krauze, who attended the same high school and accompanied him on this dangerous adventure, were lucky. They slipped unnoticed through the Polish-Czechoslovak border and made it to Prague, where they stopped at the home of Marek’s Czech friends, Bedrich Hořice, his wife, and their daughter Hanna. The pragmatic Czech family had declared their loyalty to the Communist Party, presumably to have a safer life, but Marek was convinced they would not betray him and his friend. He was right.

Marek’s Czech friends offered advice and help and did not alert the authorities. He had met them earlier during his first, also illegal, trip to Prague in 1947, which he took with his nephew Andrzej Walicki. While in Prague for the first time, Marek considered escaping to the West but decided against it, fearing that the Germans or the Americans might send him back because he was still a minor. He and his nephew, who was about the same age as Marek, returned from Prague to Warsaw.24

Two years later, after Marek had already turned 18, he again illegally crossed the Polish-Czechoslovak border. After a short stay with the Czech family in Prague, he and his friend took a train going west and jumped off before reaching the heavily guarded Czechoslovak-West German border. Despite initially losing their way and spending the night in the mountains in the freezing rain, they managed to cross the border without being spotted.

When he fled to the American zone in Germany in 1949, Marek Walicki was too young and too inexperienced to realize that the West was not going to risk another war, this time with Soviet Russia, to liberate Poland with military force. He wrote in his memoirs that he was escaping with the hope of returning as a soldier of the Polish Army under the command of General Władysław Anders, who avoided being killed in Katyn because the NKVD secret police interrogated and tortured him at the Lubyanka prison in Moscow. Stalin released General Anders and other Polish prisoners in the Gulag after signing an agreement with the Polish Government-in-Exile in London in 1941. The Soviet dictator still feared then that Hitler might succeed in conquering Russia. Evacuated by Anders from the Soviet Union to the West through Persia, Polish soldiers later fought against the Germans alongside American, British, and other allied troops, helping to liberate Italy. At the war’s end, many of them no longer had homes to return to as their towns and villages were on the territory annexed by the Soviet Union. A few returned to the new Poland under communist rule only to be arrested by the regime’s security services.

Imposition of Communist Rule

One thing Marek Walicki did not lack was courage. Even more significant was his desire shared by many Poles of all ages to see their beloved country free and democratic after the horror of the German occupation and the repressions by the Soviet-imposed communist regime. After surviving the 1944 Warsaw Uprising against the Germans, which failed because Stalin had halted the Red Army advance and blocked American and British help to the Polish non-communist insurgents, he did not want to live in a country that went from being ruled by one foreign totalitarian dictatorship to being led by a puppet government of another.

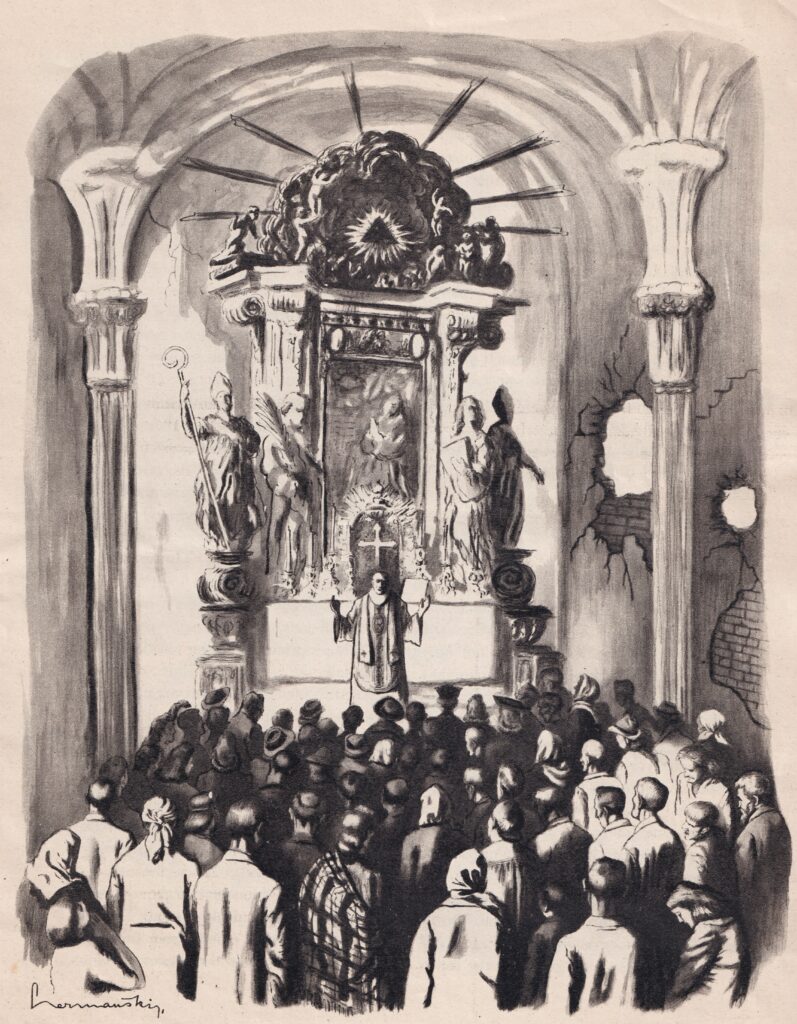

Marek Walicki’s book offers examples of how the pro-Moscow regime attempted to secure its power by attacking the Catholic Church, the only remaining independent national institution left in Poland after the war. He writes that after the Communists forbade hanging crosses in schools, he and his high school friends would bring them to their religion classes. The “war of the crosses” continued until the communist regime eliminated religious instruction in schools in 1947. The authorities later arrested Marek Walicki’s religion teacher at his school, Father Antoni Czajkowski, a Catholic priest who took part in the Warsaw Uprising. Marek wrote that the priest was tortured while being interrogated and spent seven years in prison.

Also arrested was Marek’s half-brother, Michał Walicki, who, during the German occupation, brought to his Warsaw apartment for meetings parachutists dropped in Poland by planes flown from England. Shortly after his arrest, the communist militia called Marek for an interrogation. He managed to mislead them by saying that he did not know much about his half-brother. The militia let him go free after questioning. Still, he was afraid that, if arrested again and tortured, he might break down, and he wrote that the incident only strengthened his desire to escape from Poland.

I increasingly felt that we were living in a cage, that there was no future for me there, and that, given my contrary nature, I might one-day share Michał’s fate and waste several years of my life in a communist prison. I decided to escape to the so-called West – to choose the freedom I had longed for since the German occupation.

Leaving His Parents in the Dark

To protect his parents, Marek Walicki admits that he did not tell them he would try to escape from Poland. He knew they would have wanted to stop him if he had told them about his plans and that he would have probably given up and decided to stay with them.

Their concern for his safety and well-being would not have been unfounded. He risked being shot by communist border guards or, if caught alive, being sent to prison for many years. Before departing from Warsaw on a train to the Polish-Czechoslovak border, he left a farewell letter to his parents with one of his friends with instructions to deliver it after receiving a postcard, which he promised to send from Germany to another high school friend if the escape plan succeeded. Marek’s friend delivered his letter to his parents after he was sure Marek was already in West Germany.

Marek rightly assumed that it would have been better if his parents could say, if confronted by the communist police, that they knew nothing about his flight from Poland. He was probably right in also noting that the director of his high school – a woman who had held that position since 1905 and was not sympathetic to communism – was punished for his escape. The authorities replaced her with a communist educator, but it was only a question of time before the regime would have dismissed her.

Difficult Beginnings

At first, Marek Walicki’s life in the West following his dangerous escape was far from easy and far from what he may have expected. He quickly learned he would not, as he had hoped, return to Poland to liberate it as a soldier of the Polish Armed Forces in the West. The Anders Army, as it was commonly called after its commander, General Władysław Anders, also known as the Polish Second Corps, no longer existed. General Anders would not return on a white horse to free Poland from Russian occupation, as many Poles had hoped. After fighting the Germans in Italy and on other fronts alongside British, American, and other allied forces, tens of thousands of Polish soldiers under his command were transported to Britain and disbanded. They and their comrades who died fighting the Nazis in Western Europe became an embarrassing reminder of the American and British betrayal of Poland. To avoid offending Stalin, the British government did not invite to the 1946 London Victory Parade the veterans of the Anders Army who had fought on the side of Great Britain and the United States in World War II.

The Western allies had already assigned Poland to Soviet Russia’s sphere of influence without asking or consulting the Poles or their multiparty Government in Exile in London and, accepting Stalin’s promise of “free and unfettered elections,” gave diplomatic recognition to the Soviet-imposed regime in July 1945. President Roosevelt received the Polish-American vote in the 1944 presidential elections by successfully deceiving the leaders of the Polish-American Congress, the umbrella organization of Americans of Polish descent, about his plans for Poland and the promises he had already made to Stalin and the Tehran Conference at the end of 1943.25

Marek does not say why he made erroneous assumptions about General Anders Army and the rosy Western view of Stalin’s Russia immediately after the war. Still, it is not difficult to imagine that many patriotic Poles, especially the younger ones, when faced with the brutal reality of Soviet domination of their country and communist repressions and cut off from the outside world, would embrace unrealistic hopes. More difficult to understand is how Stalin deceived the Western public opinion with the help of sympathetic press in the West to accept his conquest of East-Central Europe as a guarantee of future peace and progress – something that Ukraine has good reasons to worry about now concerning any deals proposed to end the war, with the support for Vladimir Putin’s propaganda coming this time much more from radically right-leaning American politicians and commentators as opposed to the pro-Soviet leftists of the World War II and the Cold War period who were also deceived by propaganda and supported Russia for their own ideological and partisan reasons. Marek does not mention whether, at that time in Poland, he listened to the Voice of America. However, much of Western journalism at that time was still solidly pro-Soviet, and VOA still employed until 1947 pro-Soviet broadcasters. One was Stefan Arski, a U.S. State Department-employed Voice of America editor Marek Walicki mentions later in his book. He was one of several former VOA journalists who had returned to Poland to help establish communist rule.

During a short stay in a refugee camp in Munich following his escape, Marek found out that one of the few options still open to young refugees from the Communist Block like himself was to join the Polish Guards Companies. These were paramilitary units organized by the U.S. Army in West Germany to help protect and service American military installations. The guards were recruited from former Polish prisoners in Nazi Germany, former Nazi concentration camp inmates, Poles taken to Germany to perform forced labor, and recent escapees from Poland like Marek Walicki and his friend. These refugees, removed from their homes during the war, were mainly men from poor families and without much education. Marek tried to teach a few basic math and Polish grammar, as he wrote, with some success.

Service to others and helping those less fortunate was something Marek must have learned from his parents. He mentions later in his book that during the German occupation, his mother sheltered a Jewish boy in their Warsaw apartment, thus risking the lives of their entire family, including her children. His half-brother was an active member of the anti-Nazi resistance with Marek’s father’s approval and help. Patriotism in the Walickis’ intelligentsia home was typical of other Polish families of similar backgrounds. Centered around service and loyalty to one’s country and fellow human beings as individuals, especially those needing help, it had little in common with nationalism in today’s ideologically tainted definition of the word.

As a rather private person, Marek does not flaunt his religious faith. Still, his memoir makes it clear that religion shaped his life and gave him the courage to defend the truth and stand on the side of the persecuted and the less privileged. As someone intensely loyal to his friends and family, he is not as willing to talk about private conversations as some readers may wish. It may be one of the few flaws of his otherwise invaluable memoir.

His religion and upbringing may have also made him less willing to write more about some of his noteworthy achievements and his service to others. The book leaves several questions unanswered about his choices and decisions, at least for me. For example, even though he escaped from life under communism, he nevertheless told a few of his fellow guards that they might be better off returning to Poland to go to school. He volunteered to teach some of them how to read and write when he did not see much interest among the Polish leaders in London or the Americans in Germany in the long-term welfare of these Polish war victims who never received any education. When the guards’ commanders found out that he had advised some of the guards to go back to Poland, they started to suspect him of being a “communist agitator.” He points out that the paranoia of McCarthyism was already beginning to take hold. Still, he also makes it clear that communist agents and those duped by Soviet propaganda in the West represented a real threat to freedom and human rights.

Marek’s first job in the Polish Guards was shoveling coal, but by the end of 1949, he advanced to become a military guard. His most difficult day, he wrote, was the first Christmas Eve in the West when he volunteered to be on duty to allow a married Polish guard to spend time with his family. Walking outside with his rifle along the fence surrounding the American military warehouses, he could only think of his loved ones left behind in Poland. Marek wrote that his eyes would have been full of tears that night if not for the severe winter cold stopping them from flowing down on his cheeks.

Meeting a Communist Spy

Marek Walicki’s job with the paramilitary Polish Guards did not last long. It ended after not quite half a year when, at 19, he found better employment as a secretary with Caritas, the Polish Catholic charitable organization that provided Polish refugees in Germany with food, clothing, and, to a much lesser degree, some financial help. While working for Caritas, Marek developed long-lasting friendships with several Catholic priests. But he was also disappointed that one of his more casual clerical acquittances from that period, a former prisoner in Auschwitz, Bolesław Wyszyński, was identified after the fall of the communist regime in Poland as a secret police informant, codename “Nihil.” In the 1970s, Wyszyński spied at the Vatican on visiting Polish bishops, including Cardinal Karol Wojtyła – the future Pope John Paul II. He was no relation to Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, the Catholic Primate of Poland, whom the communist regime imprisoned from 1953 to 1956.

Walicki speculates that Cardinal Wyszyński may have suspected Father Bolesław of spying and recalled him from the Vatican a few months before Wojtyła was elected pope in October 1978. After joining Radio Free Europe, Marek encountered another Polish regime spy, Zbigniew Brydak, who infiltrated the Munich Bureau of the Voice of America. Marek suspects that someone had recommended him to those in charge of VOA’s Munich office. But as titillating as these revelations about communist spies among priests and at Radio Free Europe may appear, these relatively few agents could not help subvert the Catholic Church or the American-funded radios.

The communist regimes achieved much more by misleading political elites in the West with the help of witting and unwitting agents of influence among Western intellectuals, journalists, and politicians. As Marek discovered later, some opinion makers and politicians in the West would aggressively demand the closing down of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty while being willing to tolerate continued broadcasting by the “soft” Voice of America. Later in the Cold War, some of the communist regimes indicated that they tolerated VOA as the official radio station of the U.S. government. They no longer saw VOA broadcasts as dangerous in the era of détente, while continuously demanding that Washington stop its funding of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.

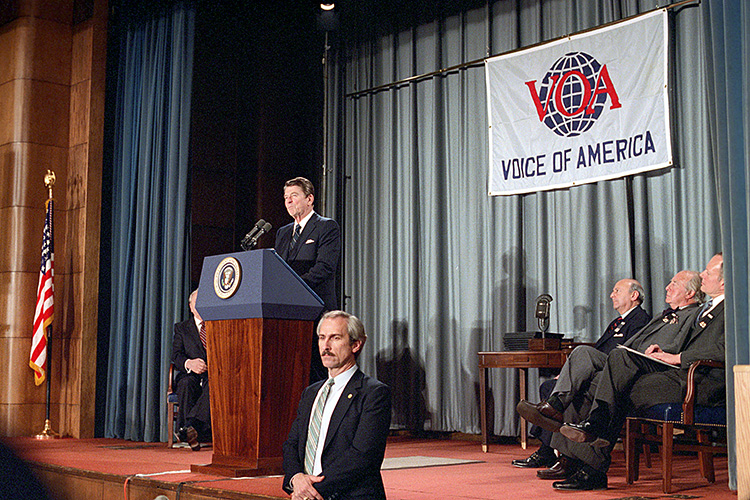

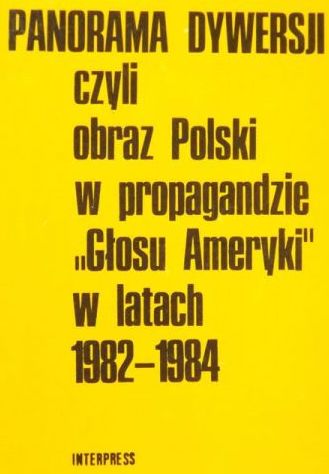

After broadcasting pro-Soviet propaganda during World War II and for a few years after the war, VOA programming became much more focused on exposing communist propaganda during the later years of the Truman administration. But, as Marek observed in his book, in the 1970s, when he started to work for the Voice of America’s Polish Service, “the most VOA could do was to send its correspondents to the Polish People’s Republic to cover the opening of the American Pavilion at the Poznań International Fair, to report on the U.S. Information Agency’s traveling exhibits or a reception at the Polish People’s Republic’s Embassy in Washington during the visit of Edward Gierek, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ [Communist] Party.” He could not get his superiors in VOA’s Polish Service to approve his requests for coverage of interesting events in Washington until the Reagan administration officials implemented management reforms in the early 1980s.

The Voice of America’s commitment to the truth and effectiveness was restored twice during the slightly more than 80 years of its existence – the first time by President Truman, a Democrat, in the early 1950s, and the second time by President Reagan, a Republican, in the early 1980s. What mattered the most in the case of the Voice of America was the presidential leadership, the experience and skills of agency and VOA leaders, and the background and the quality of VOA journalists. Still, even the most experienced, skillful, and least partisan VOA leaders and journalists found it difficult to compete effectively for audience and impact with Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.

A Young Journalist

Marek Walicki started to pursue a journalistic career while still a guard for the U.S. Army, at first as a photojournalist. Using the money he saved, he bought a used Leica camera and freelanced for a Polish Catholic weekly paper, Słowo Katolickie (Catholic Word), published in Paris. At that time, he became a member of the International Federation of Free Journalists of Central and Eastern Europe, Baltic and Balkan Countries and joined the Association of Polish Journalists in Germany.

Although able to work remotely for a Polish magazine published in Paris, Marek noted that the American, British, and French authorities, still afraid of upsetting the Soviets, shut down dozens if not hundreds of Polish-language publications in their respective occupation zones in Germany. He may not have known at the time that a few years earlier, officials of the U.S. government agency that had managed the Voice of America since 1942 had managed to silence during the war a few Polish-American radio programs for exposing Stalin’s crimes and made another illegal though unsuccessful attempt to shut down a Polish-American newspaper, which would later tell how in its propaganda campaign to protect Stalin’s reputation, the U.S. government’s information agency lied to American media and audiences overseas about Polish orphan children rescued from Soviet Russia.26

When Marek Walicki got to West Germany, the honeymoon between the U.S. government and communist regimes was near its end. But, as he points out in his book, the Western occupational authorities in Germany had forcefully sent some of the former Polish slave laborers to communist-ruled Poland. While such forced deportations from the West of Polish and other Eastern European refugees soon stopped, Marek Walicki’s book reveals the hidden truths about how the U.S. government had collaborated earlier with Soviet Russia in supporting Stalin’s takeover of Eastern Europe. President Truman eventually put a stop to the policy of appeasing Soviet Russia.